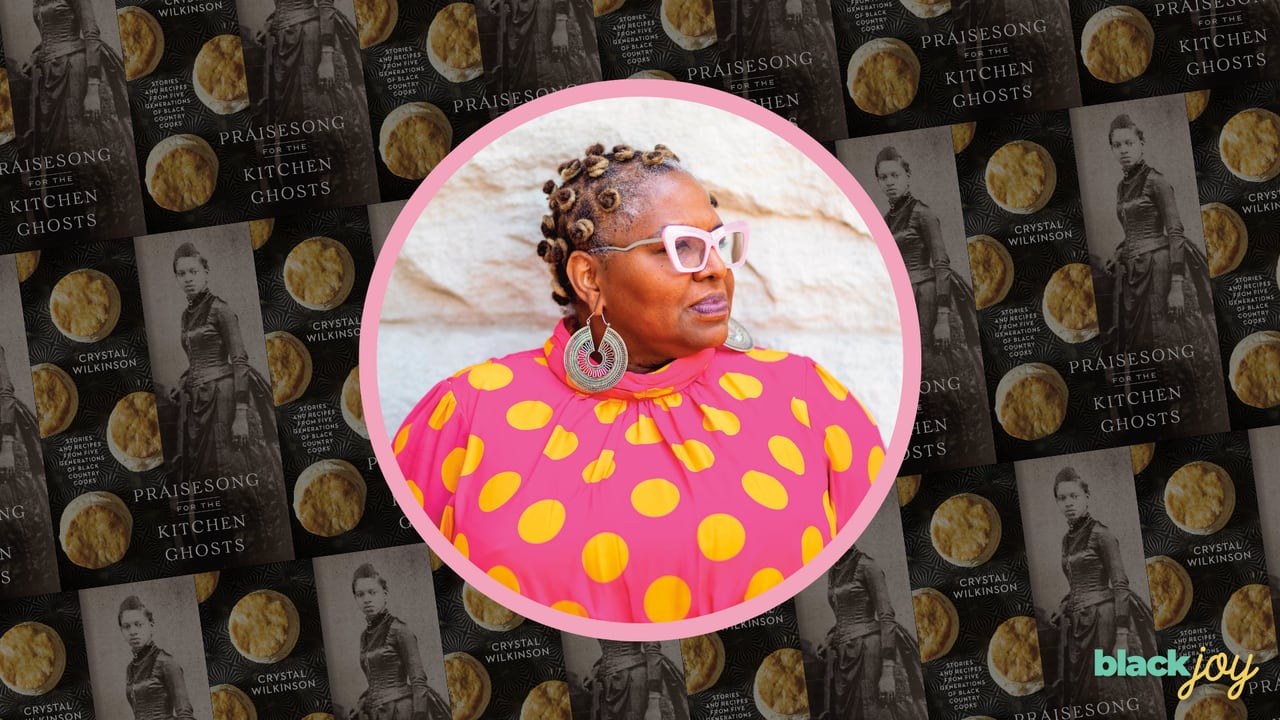

Crystal Wilkinson on land, healing, and family recipes in âPraisesong for the Kitchen Ghostsâ

Some of my most vivid memories from childhood take place in the kitchen. Like during the holidays, when my late great-aunt’s house became crowded with folks—the elder women bustling from stove to table, the men standing around the table waiting to begin the family prayer, heat and the aroma of chicken and turnip greens and fresh cornbread made-from-scratch engulfing us. And laughter. There was always laughter (and some fussing) that filled the house. This scene from my childhood is a familiar one, an extension of a shared legacy among Black folks, especially those of the rural South.

In her memoir-cookbook, “Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts,” Crystal Wilkinson invites us into her kitchen, but also into her family’s story—five generations of Black Appalachian country folk. Wilkinson teaches us how food holds memories, how cooking can be a kind of time-traveling as the steam from a pot of butter beans transports you back to standing in your granny’s kitchen watching her move with tenderness and precision. Each recipe Wilkinson gifts to us tells a story not just about Black Appalachian life, but about our history as Black folks in this country.

She writes: “I am the keeper of the stories, the writer, the one who has carried the stories in my apron for so many years, the one who considers a rusty metal recipe box my finest family heirloom. I am the one who makes a pot of chicken and dumplings and cornbread, who conjures up the kitchen ghosts of my rural homeland every time I cook.”

Wilkinson sat down with Black Joy to discuss the role of her ancestors in piecing together parts of her family history, her thoughts on the sacredness of family recipes and share some of her favorite childhood memories involving food and family.

Tell me about the process of excavating your family history dating back to your fourth great-grandmother, Aggy. What steps did you take to find this information?

The woman who’s on the book cover, Patsy Wilkinson Riffe, is grandma Aggy’s daughter. My grandmother would always say there was a ridge back home called Patsy Riffe Ridge [and she] would always say, ‘Oh, you know, Patsy Riffe was a colored woman [and] she’s somewhere kin to us.’ That always sort of stuck with me. And so I was at a writing retreat and I had planned on writing these short flash essays about my grandmother. And the idea was to gather as many Black women in my family as I could and go back as far as I could. And so I kept going back and then when I got to Aggy everything sort of stopped. I knew that if she was born in 1795 that I had come up on something because she was right there during the time of enslavement.

The weight of that hit me and I became sort of haunted by her in some ways. I couldn’t find a lot because she was a Black woman born in 1795. But I became almost obsessed with it in trying to find out everything that I could about her. So I did the typical sort of genealogical searches. I went through Ancestry.com, I went through other online searches. I went to court records from my hometown online. When I got home from the retreat, I physically went to the courthouse in my hometown and began to look for documents. It became so important to me to try to find everything there was about her. And then I reached a point where I couldn’t find anything else about her. And that was devastating for me and, as I know, that’s part of our devastating history in this country.

Before I came home [from my writing retreat], I had been up all night searching little bits of information that I could find online in my hometown and through the Kentucky State Department. And I went to sleep with her on my mind and I woke up and every morning when I was there, I would take a walk on the beach, this sort of cleansing walk before I would come back and start writing. And I woke up that morning with her in my head and her saying my mother speaks to me, but not in your language. My mother calls to me, but not in your language. And I was like, oh my gosh, am I dreaming? Have I conjured her spirit? Is this what’s going on? And from that moment, I felt like I had to find out everything there was to know about her, whether that meant through spirit, through imagination, through intuition, through divination, through research.

For a lot of families, including yours, certain recipes are sacred. I know there are women in my family who have passed on and took certain recipes with them. You offer so much in this book. Recipes that are ancestral but also very specific to our lineage as Black people. Were there any recipes that you withheld that were too sacred for you to share with the public?

Not really. I feel like I’m sort of in trouble with some of my family members. Even my son said, mama don’t be telling all the secrets. And I thought, well, these are common foods that everybody makes differently. My grandmother sort of gave her recipes freely. What’s funny is that we still don’t know if we have the recipe or if she took it with her. There’s this sort of back and forth about, particularly, the jam cake. I got so tickled because I have probably four different versions. And so, I presented in the book, the version that I like, which did come from her, but there’s varying recipes and it’s a recipe that she had already published in—you know how the church ladies used to have those little church cookbooks that they would put together. And so her recipe, that particular jam cake recipe, is in one of those.

There was a white lady that she used to work for that sent me [one of my grandmother’s recipes] and she sent like yet another version. And I just got tickled because I was like, ain’t no telling if this is the real one or not. And I feel like that’s part of the legacy too of so many of us. Yours doesn’t taste like your aunties or your mother’s or your grannies because they cook by sight, not really by recipe. So, you make it and it ends up tasting different because they weren’t standing over your shoulder saying, ‘Oh no, that don’t look right, add more, you need to add some more milk.’ So, I think sometimes we romanticize the idea of the secret spices that nobody else knows about. I felt like all of those recipes are fairly common. Some of them are me trying to get close to my grandmother’s recipe. So, why not share some of the secrets? Maybe I held back. I ain’t telling, maybe I held back a little bit.

Aside from in the kitchen, in what other ways have your ancestors communicated with or visited over the course of your writing career and while writing this book?

I feel like that as a writer, I’ve always wanted to pay homage to my ancestors in some way. It’s always been important for me. It’s always been important for me to get the rural Black story down and for readers to know and for audiences to know that it is not always just a story of the past, that there are still some of us that are living in rural areas. And it’s history, but it’s also a living legacy. It’s still part of us. The capacity of nature to heal, particularly to heal Black women, I think is tremendous. And we don’t tap into it enough because we feel like our connection to the land is distant, but it’s with us. Some of us still live in those areas. But even if you don’t, it’s still in you to be able to tap into that and to take advantage of that ancestral memory.

So that kind of thing has always been important, and it always shows up in my writing—my connections to the land, connections to water, connections to spirit, connections to the past. And in writing this particular book, it was, of course, very, very present all the time. It was important for me to talk to my elders. I spent a lot of time talking to my auntie who’s 86 my uncle’s right at 80. And so, they’re like the last ones that are left. And I spent a lot of time talking to them. I spent time talking to my older cousins and I spent a lot of time sort of communing with the ancestors and saying, you know, speaking to my grandmother and even my mother who’s passed and grandma Aggy and saying, ‘OK, did I get this right?’ Or ‘If I didn’t get this right? Is this close enough, you know, do y’all approve?’ And so having that sort of conduit in that communication whichever way it took was very important in writing this book.

You shared so many beautiful memories from your childhood centering around food. If you had to choose one, what’s your most joyful memory involving food and family?

Well, it’s hard to choose just one. I could almost pick any holiday and, and those would be wonderful. So, there were holidays, whether it was Easter or Thanksgiving or Christmas, and those special foods that were cooked were very memorable. But I have to say that, being my mother’s only child and being, being grandparent raised that, my other favorite memory is just sort of watching my grandmother cook, even as a little, very small girl standing up in the chair, just watching her do her thing and thinking about that even now, even now that I have Children and even have grandchildren of my own, I often go to that memory when I’m cooking. You know, if the steam hits a certain way, I think of me as a little girl standing up and trying to peep over into the pot to see what it looks like.

Did you have any other final thoughts you want to share or maybe something I didn’t mention that you just want to add?

Well, the only thing that I would like to share is that I think this is a very personal book and it’s very particular to me and my family. But I think the most special thing about it is that it travels, it doesn’t just stay with me and my family, it brings up in people a wealth of memories of their own. And I hope that that’s what it will continue to do, that when people read about my kitchen ghosts that they’ll begin to think about their own and do their own work of discovery to find out who their own kitchen ghosts were and how their culture and their family and their ethnicity was influenced by the foods that were cooked.