Congressional divorce occurring in South Alabama over redistricting

Republican and Democratic politicians in Mobile and Baldwin counties are readying for a congressional divorce and are continuing to hold differing views on a key principle in redistricting over what constitutes “communities of interest.”

For Republicans, the two counties are forever linked because of their close proximity, shared economic interests, jobs and infrastructure.

“Mobile and Baldwin counties have far more in common than Mobile and Montgomery do,” said Bradley Byrne, president & CEO of the Mobile Chamber who served as the representative for the 1st congressional district from 2014-2021.

“Our economies are interwoven between the two and have been for centuries,” he added. “We are one thing, if you stop and think about it. We are not one thing with the Wiregrass, or the Black Belt or Montgomery. It’s different.”

But for Democrats, portions of the two counties have very little in common – Republicans dominate in the majority white Baldwin County, while Democratic politicians in the majority Black areas of Mobile and Prichard and North Mobile County have more political similarities with the Black Belt region of Alabama and the City of Montgomery.

In the South, where racial polarized voting has long underscored politics, the redistricting plans under consideration better reflect political realities, the Democrats say.

“We are not really like Baldwin County,” said state Rep. Sam Jones, D-Mobile, who served as Mobile’s first Black mayor from 2005-2013. “Baldwin County has much lower poverty levels than Mobile County. Mobile County basically has industry and is an economic hub for the region. Baldwin County is more a recreational and tourism county than anything else.”

He added, “Because we have a highway that adjoins to Baldwin County doesn’t mean we’re a community of interest.”

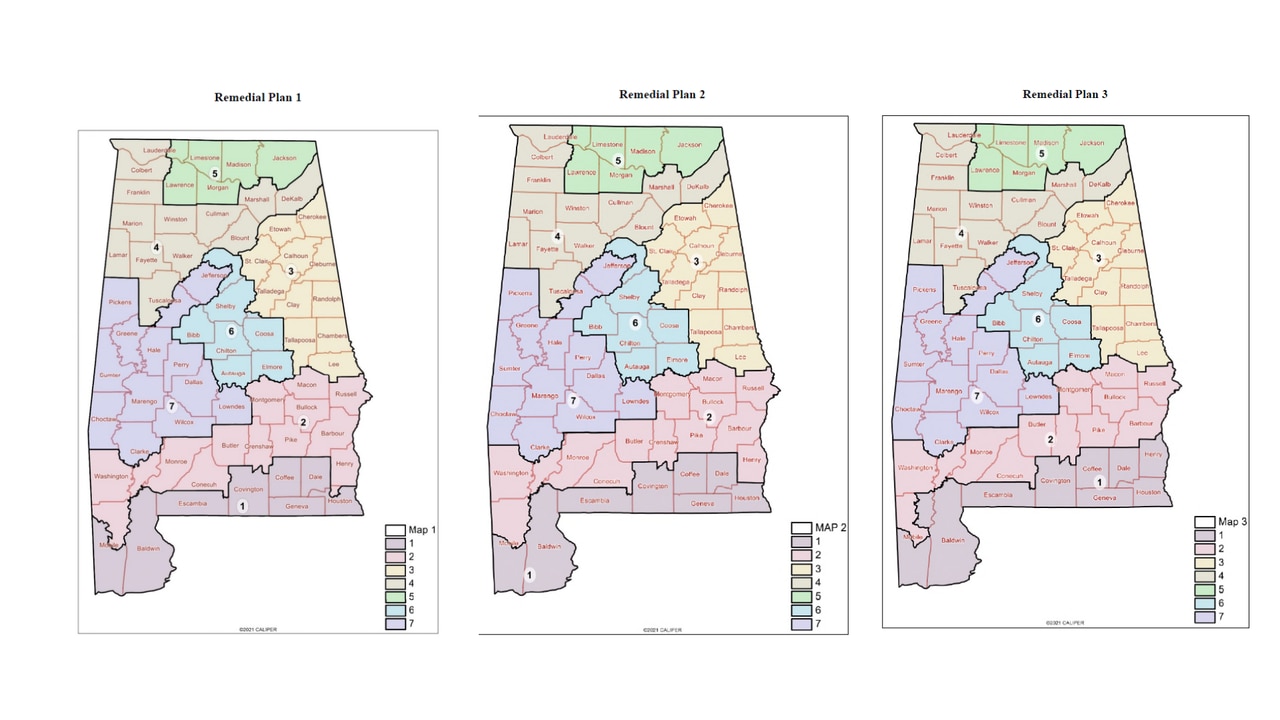

Alabama recommended congressional redistricting maps

The splintering of the two coastal counties after 40 years of conjoined congressional representation continues to be a subplot in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on Tuesday to not grant a reconsideration of Alabama’s proposed congressional map. The Legislature, which is a supermajority Republican, drew a map that keeps Mobile and Baldwin counties together.

Republicans argued their plan upheld the communities of interest principle of redistricting “fully and fairly.” A community of interest, by definition, is a neighborhood or group of people who have common policy concerns and would benefit from being maintained in a single district.

A community of interest can be defined in many ways. Race and ethnicity can play a role, but it cannot be used as the sole definition. Other examples include proximity, such as community members living in a similar area who advocate for getting special recognitions for cultural holidays – like Mardi Gras Day, shared by both Mobile and Baldwin counties – or getting assistance to repair an area following a natural disaster.

A majority of the U.S. Supreme Court in June was not swayed by arguments that Mobile and Baldwin counties should remain connected to the same congressional district because they shared a distinct community of interest. The high court then ruled that the Republicans map is likely a violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, because it maintained one majority-Black district out of seven in a state that is 27% Black.

The map drawn by Republicans during a special session in July did not add a second majority Black district, and the Supreme Court rejected the state’s emergency stay to use their proposed map for the 2024 election.

Black Belt connections

The ruling on Tuesday all but assures that a court-appointed Special Master’s map will go forward soon. All three proposed maps under consideration include areas within the majority Black portions of Mobile that are part of the 2nd congressional district that includes the Black Belt and Montgomery. Baldwin County and South Mobile County will be part of a newly drawn 1st congressional district that extends east through the Wiregrass.

Rep. Barbara Drummond speaks to the House Judiciary Committee April 12, 2023, regarding her proposed safe storage bill. Sarah Swetlik/AL.com

State Rep. Barbara Drummond, D-Mobile, said it’s a scenario that makes sense for Mobilians. She said it’s not uncommon for Black Mobile residents to have generational connections with the Black Belt.

She said her family has roots in Dallas and Sumter counties, and that her parents moved to Mobile for job opportunities.

“That’s our community of interest which I still have relationships with and I am happy that Mobile is included in all three of the remedial plans submitted to the Special Master,” Drummond said. “I am more elated because I think it will give a fair opportunity for those that are affected … Black Alabamians and, for me specifically, Black Mobilians, to have an opportunity to vote on a congressional seat that has been tailored to their population.”

The newly drawn 2nd congressional district will have a voting age population that is at or near 50% Black. The current district, represented by Republican U.S. Rep. Barry Moore of Enterprise, is 61% white, 31% Black.

State Rep. Napoleon Bracy, D-Prichard; and State Rep. Sam Jones, D-Mobile; on the floor of the Alabama House of Representatives on Tuesday, April 18, 2023, at the State House in Montgomery, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

State Rep. Napoleon Bracy, D-Prichard, said that Prichard and north Mobile communities like Toulminville are about to merge into a congressional district with more shared interests than Baldwin County.

“When you look at cities like Prichard and areas like Toulminville and other parts of the City of Mobile like Africatown, you can’t look at those areas an say they are communities of interest with an Orange Beach or a Fairhope,” she said. “They are not community of interest in the same manner. I never bought that argument that Mobile and Baldwin counties had to stay together.”

Racial polarized voting

Republicans like Attorney General Steve Marshall say that the Supreme Court’s decision on Tuesday “racially gerrymandered” voters and accused the courts of applying “race above all else.”

A study published in June in the American Political Science Review illustrates that Alabama and Mississippi, more than any other state in the U.S., has the highest racial gaps among voters. In South Alabama, the gap between white and non-white voters is 60 to 70 percentage points – meaning that white voters are mostly aligned with the Republican Party, while Black voters are with the Democratic Party.

Sprawling Baldwin County, over the past 52 years since the 1970s Census, has grown over 314 percent, but it remains an overwhelmingly white county. The 2020 Census shows only 8.6% of the county’s population as Black. The more urban Mobile County is 37% Black. The City of Mobile is majority Black, and Prichard – with a population around 20,000 residents – is 91% Black.

Sen. Vivian Davis Figures (D-Mobile) speaks to a colleague during the first meeting of the Alabama Senate for the 2023 legislative session in Montgomery, Alabama. AL.com/Sarah Swetlik

State Senator Vivian Figures, D-Mobile, said the new 2nd congressional district represents a “great opportunity” for a second Black member of Congress from Alabama, and to have a Democratic lawmaker from South Alabama.

“What to me is significant is to have one of those Congress members to be of African American descent,” Figures said. “We’ve had one African American (in Congress, U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell of Birmingham) and that’s been in the Northern and Central part of the state. Now is the time for southern Alabama to have that African American representation as well.”

Differing interests

Republicans say the true communities of interests are shared geographic and economic benefits and attractions.

It was a concern raised in June by Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who said it was “indisputable” that the Gulf Coast region is a community of interest that the Alabama Legislature “might reasonably think a congressional district should be built around.”

He was in the minority. Chief Justice John Roberts found that some regions had to be split up so that others could be united.

Mobile County Commissioner Connie Hudson speaks during a news conference on Wednesday, December 15, 2021, at Government Plaza in Mobile, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Mobile and Baldwin counties are separated by less than 20 miles, connected by the Interstate 10 Bayway and the Spanish Fort Causeway. A congressional split “could be detrimental to the existing Mobile-Baldwin alliance,” said Republican Mobile County Commissioner Connie Hudson.

“The Alabama Coastal counties share many common interests and projects that have received federal support such as the proposed I-10 Mobile River Bridge and Bayway project and GOMESA funding, and both counties are closely intertwined in many largest-scale economic development projects, including the Port of Mobile,” she said. “To basically split off the majority of north Mobile County, including the City of Mobile into a separate district that stretches to Montgomery and eastward away from the coast could undoubtedly dilute our coalition’s effectiveness in lobbying for needs of Coastal Alabama and could potentially impact projects that are critical to South Alabama and the state,” she said.

Patrick McWilliams, chairman of the Baldwin County Republican Party, speaks during a luncheon hosted by the Eastern Shore Republican Women on Thursday, Sept. 14, 2023, at the Fairhope Yacht Club in Fairhope, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Patrick McWilliams, chairman of the Baldwin County Republican Party, said the new map places Baldwin County within a district that stretches to the Dothan area and beyond. He said congressional priorities are completely different within the newly drawn district and could create frustrating scenarios.

“Are people from Foley going to care about the four-laning of roads in Dothan?” he said. “And in the same breath, are Dothan folks going to care about the Mobile River Bridge project? The answer to both of them is ‘No.’”

Alabama State Senator Greg Albritton takes questions from the media on Thursday, April 29, 2021, at the State House in Montgomery, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

State Senator Greg Albritton, R-Atmore, said any notion that Mobile shares a community of interest with the Black Belt “is a stretch.” He said that residents in Jackson or Atmore – who would be placed in a different congressional district than Mobile or Baldwin counties – travel more frequently to Mobile for work and entertainment.

“We have teachers driving from Monroeville to Mobile and back, and the school superintendent of Escambia County is from Mobile,” Albritton said. “There is a connection there with families and economics of roads and everything that ties into it. The connections with Selma are few and far between.”