Community colleges are struggling. Why are students leaving?

This story was produced by a collaborative of newsrooms for a series, “Saving the College Dream.” Ellen Dennis, freelancing for the Seattle Times, Rebecca Griesbach of AL.com and Ira Porter of the Christian Science Monitor contributed reporting.

When Santos Enrique Camara arrived at Shoreline Community College in Washington State to study audio engineering, he quickly felt lost.

“It’s like a weird maze,” remembered Camara, who was 19 at the time and had finished high school with a 4.0 grade-point average. “You need help with your classes and financial aid? Well, here, take a number and run from office to office and see if you can figure it out.”

In high school, he said, “it’s like they’re all working to get you through.” But at a community college, “it’s all on you.”

Advocates for community colleges defend them as the underdogs of America’s higher education system, left to serve the students who need the most support but without the money required to provide it.

Read more Alabama Education Lab coverage here.

Critics contend that this has become an excuse for poor success rates that are only getting worse and for the kind of faceless bureaucracies that ultimately prompted Camara to drop out after two semesters; he now works in a restaurant and plays in two bands.

“I seriously tried,” Camara said. “I gave it my all. But you’re sort of screwed from the get-go.”

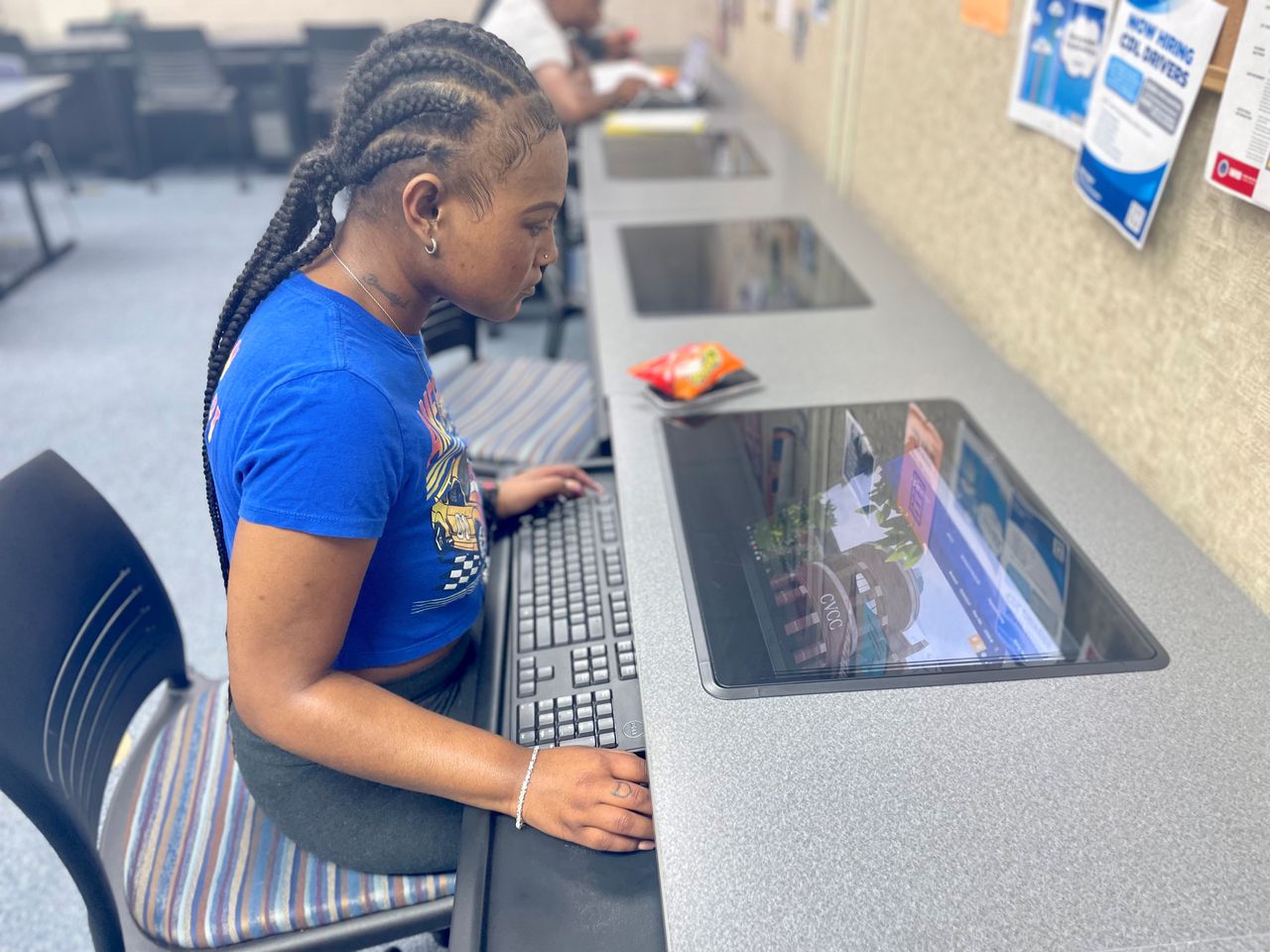

Oryanan Lewis, 20, also struggled to find her way at Chattahoochee Valley Community College in Phenix City, Alabama, where she is pursuing a degree in medical assisting.

Lewis has the autoimmune disease lupus and thought she’d get more personal attention at a smaller school than at a four-year university; Chattahoochee has about 1,600 students. But she said she didn’t receive the help she needed until her illness had almost derailed her degree.

“It was just like I was in a place by myself,” she said of how the college failed to respond when, two months into her first semester, she got sick — even when she reached out for support and stopped logging into the system that was supposed to track her progress. She ended up failing three classes and was put on academic probation.

Only then did she hear from an intervention program.

“I’m ready for this to be over with,” said Lewis. “I feel like they should talk to their students more. Because a person can have a whole lot going on.”

Oryanan Lewis works in the computer lab at Chattahoochee Valley Community College in Phenix City, Alabama, Feb. 23, 2023. She has an autoimmune disease and nearly had to drop out of community college due to sickness, but, through support, got back on track and is now finishing her second year of a medical assisting degree. Rebecca Griesbach/AL.com

With scant advising, many community college students spend time and money on courses that won’t transfer or that they don’t need. Though most intend to move on to get bachelor’s degrees, only a small fraction succeed; fewer than half earn any kind of a credential. Even if they do, a new survey finds that most employers don’t believe they’re ready for the workforce.

Now these failures are coming home to roost.

Even though community colleges are far cheaper than four-year schools —published tuition and fees last year averaged $3,860, versus $39,400 at private and $10,940 at public four-year universities, with many states making community college free and President Joe Biden proposing free community college nationwide — consumers are abandoning them in droves.

Poor success rates

“The reckoning is here,” said Davis Jenkins, senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center, or CCRC, at Teachers College, Columbia University. (The Hechinger Report, which produced this story, is an independent unit of Teachers College.)

Although the enrollment drop-off sped up during the Covid-19 pandemic, it started long before then. The number of students at community colleges has fallen 37 percent since 2010, or by nearly 2.6 million, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Those numbers would be even more grim if they didn’t include high school students taking dual-enrollment courses, who the colleges count in their enrollment but on whom they’re losing money, according to the CCRC. High school students now make up nearly a fifth of community college enrollment and at 31 community colleges, the majority of it.

Yet even as these colleges serve a significantly smaller number of students, their already low success rates have by at least one measure gotten worse.

Two-year community colleges have the worst completion rates of any kind of universities and colleges. Like Camara, nearly half of students drop out, within a year, of the community college where they started. Only slightly more than 40 percent finish within six years. That was up by just under 1 percentage point last year from the year before.

So long do some students churn through community colleges, it’s become a pop-culture punch line. “You can’t expel Britta,” went a joke in the sitcom “Community,” about a community college. “She’s been here six years. Three more and she’ll have her two-year degree.”

While four out of five students who begin at a community college say they plan to go on to get a bachelor’s degree, only about one in six of them actually manages to do it. That’s down by nearly 15 percent since 2020, according to the clearinghouse.

“When we talk about transfer students, I just want to cry. And the sad thing is, they blame themselves,” said Jenkins.

Because of an “underinvestment” in advising, for example, community college students in California who transfer to four-year universities end up taking an average of 26 more credits than they need in a process that is “far more difficult and complex than it needs to be,” the Campaign for College Opportunity found.

“You’re not helping students see a path,” said Jenkins. “You’re not providing a well-structured, intentionally designed and delivered program that leads to family-sustaining wages. You’re still in the main being a course supermarket.”

These frustrated wanderers include a disproportionate share of Black and Hispanic students. Half of all Hispanic and 40 percent of all Black students in higher education are enrolled at community colleges, the American Association of Community Colleges, or AACC, says.

“If we’re serious in this country about diversity, equity and inclusion, community colleges are where these students are learning,” said Martha Parham, the AACC’s senior vice president for public relations.

The large-scale spurning of community colleges has important implications for the national economy, which relies on graduates of those schools to fill many of the jobs in which there are already shortages, including as nurses, dental hygienists, emergency medical technicians, vehicle mechanics and electrical linemen, and in fields including cybersecurity, information technology, construction, manufacturing, transportation and law enforcement.

Matching students, jobs and classes

In some of these areas, community college officials concede, the problem isn’t too little demand; it’s too much. Nursing programs, for example, have long waiting lists because of a lack of instructors and capacity.

When she asked student nurses at a hospital why they were going to a for-profit university, said Parham, they told her it was because the wait to get into the same program at the local community college was six months to a year.

For reasons like this, community colleges continue to lose prospective students to for-profit institutions, despite the fact that for-profits often have worse labor outcomes that can include lower job placement rates and postgraduate earnings and higher costs that lead to more debt.

Other factors are also contributing to the huge enrollment decline at community colleges. Strong demand in the job market for people without college educations has made it more attractive for many to go to work than to school. Thanks to so-called degree inflation, many jobs that do require a higher education now call for bachelor’s degrees where associate degrees or certificates were once sufficient, drawing students to four-year universities. And private, regional public and for-profit universities, facing enrollment crises of their own, are competing to steal away high school graduates who might be considering community college.

Santos Enrique Camara, who dropped out of Shoreline Community College at age 19 in 2015, prepares food at Capers + Olives Friday, March 24, 2023, in Everett, Wash. where he works as a sous-chef and cook. Camara, now 27, had difficulty paying tuition and finding time to do schoolwork while caring for his younger sister. ÒI seriously tried,Ó he said. For now, Camara is happy working his restaurant job while planning a tour with one of his two bands. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)AP

Many high school graduates are increasingly questioning the value of going to college at all. The proportion who enroll in the fall after they finish high school is down from a high of 70 percent in 2016 to 63 percent in 2020, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That’s the most recent period for which the figure is available.

But they are particularly rejecting community college. In Michigan, for instance, the proportion of high school graduates enrolling in community college fell more than three times faster from 2018 to 2021 than the proportion going to four-year universities, according to that state’s Center for Educational Performance and Information.

There are 936 public community colleges in the United States, and each is different. Some are working to reverse these trends by changing their cultures.

Amarillo College in Texas, for example, used data to create a composite profile of the average student, which it calls Maria: first-generation, part time and Hispanic, and a mother of 1.2 children who is 27 and works two part-time jobs. The idea is to foster empathy for all students among everyone from faculty members to cafeteria workers.

“Your first and foremost job is to make sure ‘Maria’ is successful,” Parham said. “We’re definitely seeing those kinds of models across the country.”

There’s unmistakable irony in having to create a composite student to encourage support for actual living ones, however.

It shouldn’t be that complicated, Jenkins said.

What community colleges need to do, he said, is “focus on students’ motivation, and help them plan and make sure their programs — the content and the delivery — enable very busy students in a relatively short amount of time and at a low cost to get out with a degree.”

Little support

That’s not the experience many students say they’ve had.

Megan Parish, who at 26 has been in and out of community college in Arkansas since 2016, said she waits two or three days to get answers from advisers. Hearing back from the financial aid office, she said, can take a month. “I’ve had to go out of my way to find people, and if they didn’t know the answer, they would send me to somebody else, usually by email.”

The Los Angeles City College stands in Los Angeles on Sept. 2, 2021. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)AP

Community college students’ lives “don’t fit into these nice, neat little boxes,” said Darla Cooper, executive director of the nonprofit Research and Planning Group for the California Community Colleges.

“What I’m hearing from students is, ‘This system is not built for us,’ ” said Cooper. “It has to do with everything, outside and inside the classroom: When are classes scheduled? When are services open? We talk a lot about meeting students where they are, but are we? If we were doing that, things would look a lot different.”

Older students at community colleges are as ill-served as traditional-aged ones, Jenkins said; they need rolling start dates, classes at night and on the weekends and accelerated programs.

“Community colleges don’t treat adults well,” he said. “They don’t treat part-time students well, who are predominantly adults.”

David Hodges was one of those. Hodges, 25, enrolled at Essex County College in New Jersey, to move beyond the odd jobs he’d been working since high school, including seasonal gigs at Amazon and FedEx.

But he was stymied by red tape.

Hodges said he called and visited the school to try to get information about enrolling, but kept being told that he needed his mother’s tax information to get financial aid.

“I was 24. I told them that I’m an adult. I don’t live with my mother anymore. She lives in a different state.”

Finally, the college told him he needed to take remedial courses in writing and math, for which he paid $1,000 out of his own pocket.

Hodges, too, soon dropped out.

Employers’ needs

Employers, meanwhile, are unimpressed with the quality of community college students who do manage to graduate. Only about a third agree that community colleges produce graduates who are ready to work, according to a survey released in December by researchers at the Harvard Business School. Only about a quarter strongly agree.

Economic necessity and attention to diversity have prompted politicians, policymakers and employers to try to help address the ailing fortunes of community colleges.

Dell Technologies started a program in 2020 called AI for Workforce, which was joined by Intel in 2021 and helps engineering and technology students at community colleges get certificates or associate degrees in artificial intelligence.

Tesla started working in 2018 with community colleges to train students for certifications in automotive manufacturing and service; along with Panasonic, it began another partnership in January to provide apprenticeships in the electronic vehicle industry for community college students.

Initiatives like these are a way to diversify the workforce, Dell officials said at the time.

“We reevaluated our structure on the heels of [the 2020 killing of] George Floyd to determine what we were doing and what our answer was going to be,” said Robert Simmons, the company’s talent acquisition senior manager. “The solution was to expand our definition of what we consider to be recent graduate talent to include associate degrees, apprenticeships and certificate programs,” instead of just bachelor’s degrees.

Despite the splashy announcements when these programs began, it’s difficult to learn how well they’re working. Intel and Tesla did not respond when asked how many students have participated in and completed the programs, and Dell said it could not yet share those numbers. Maricopa Community Colleges, where the AI for Workforce program was piloted, did not respond when asked how many students were in it, how many have finished and where they’re working now.

The state of Michigan is trying to prod more people there to go to community colleges with its Michigan Reconnect program, which provides free community college tuition to residents 25 and older. More than 24,000 have enrolled through the program and 2,000 have completed a degree or a certificate, according to the Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity, and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has called for further expanding it.

And in Texas, a commission has proposed tying an additional $600 million to $650 million in funding for community colleges over the next two years to the proportion of their students who graduate or transfer to a four-year university.

That’s the kind of money community colleges say they need, considering how much less funding they’re allotted, per student, than public four-year universities: $8,695, according to the Center for American Progress, compared to $17,540. Community colleges get less to spend, per student, than the average that the Census Bureau says is spent per student in kindergarten through grade 12.

Nor can community colleges rely on the other streams of revenue that shore up their four-year counterparts, such as research grants and philanthropy. Research universities that responded to a survey reported that they raised an average of $121 million apiece last year, while public community colleges collected an average of $2.7 million each, according to the Council for Advancement and Support of Education — down 15 percent from the year before.

Yet community college students need more support than their better-prepared counterparts at four-year universities. Students from the lowest-income families who pursue degrees are more likely to begin at a community college than a four-year university, the National Center for Education Statistics reports. So close to the financial edge are many of them that the colleges are stretched to help them find food and housing, adding food pantries and emergency grants.

Twenty-nine percent of community college students are the first in their families to go to college, 15 percent are single parents and 68 percent work while in school. Twenty-nine percent say they’ve had trouble affording food and 14 percent affording housing, according to a survey by the Center for Community College Student Engagement.

Even if they had enough advisers, students like these often wouldn’t know the right questions to ask, said Joseph Fuller, professor of management practice at Harvard Business School and co-author of that study of employers.

“They do have ambition, but they’re worried about discussing it with anybody for fear they’re going to be told it’s unrealistic or a dumb idea,” he said. “And that just makes you want to cry.”

Community colleges that fail these students can’t just blame their comparatively smaller budgets, he said. “The lack of resources inside community colleges is a legitimate complaint. But a number of community colleges do extraordinarily well. So it’s not impossible.”

One higher education consultant, who asked not to be named when speaking about a sector from which she makes her living, was more blunt about the state of community colleges.

“We have let them off the hook for too long,” she said.

This story about community colleges was produced by The Hechinger Report, as part of the series Saving the College Dream, a collaboration between Hechinger and Education Labs and journalists at The Associated Press, AL.com, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News in Texas, The Seattle Times and The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina.