Cancer-linked ‘forever chemicals’ detected in these Alabama rivers

A large-scale water sampling program has confirmed the presence of PFAS, or so-called “forever chemicals,” in dozens of rivers across the United States, including eight in Alabama.

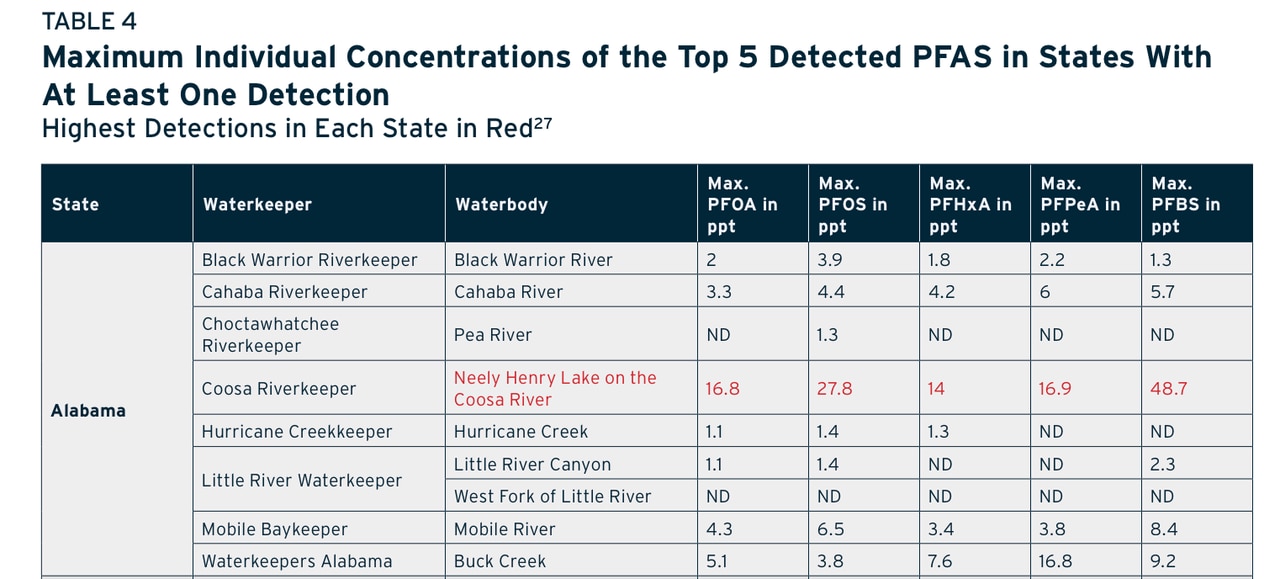

The sampling, conducted by the environmental group Waterkeeper Alliance and its affiliates, found PFAS chemicals in 95 of 114 waterways sampled, including the Coosa, Cahaba, Black Warrior, Mobile, Pea and Little Rivers, as well as Buck Creek and Hurricane Creek.

The Coosa River at Neely Henry Lake contained the highest levels of PFAS of anywhere in Alabama, showing 13 different PFAS chemicals at levels up to 4,000 times higher than health advisory thresholds issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for drinking water.

Coosa Riverkeeper Justinn Overton, who directed the sampling on the Coosa, said the results confirm that PFAS pollution is a widespread problem, in Alabama and across the country.

“Our organization really is trying to raise awareness about what PFAS are and what it means for your health and how to reduce your exposure through your drinking water as well as if you are eating fish from the river system,” Overton said.

The samples were conducted between May and July by Waterkeeper groups across the country. In Alabama, Coosa Riverkeeper, Cahaba Riverkeeper, Black Warrior Riverkeeper, Little River Waterkeeper, Choctawhatchee Riverkeeper, Mobile Baykeeper and Hurricane Creekkeeper all participated in the program.

Alabama’s results from widespread PFAS chemical sampling conducted by Waterkeeper Alliance groups in the state in the summer of 2022.Waterkeeper Alliance

PFAS are man-made chemicals that have been used in a wide range of consumer products since the 1940s, including stain-resistant and non-stick coatings on fabrics and cookware, as well as food packaging, waterproof coatings and fire-fighting foams. These chemicals are extremely durable and do not break down readily in the environment, and have been shown to accumulate in the tissues of humans and animals.

Exposure to high levels of these chemicals in the blood (mostly through drinking water) have been connected to increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, as well as liver damage, high blood pressure, and increased cholesterol levels, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

At present, there is no evidence that swimming or incidental contact with PFAS-contaminated waters could lead to health problems. But it could be a problem if there are even trace amounts in your drinking water, or if your diet includes large amounts of fish taken from PFAS-contaminated waters. Since the chemicals do not readily break down in the human body, they can accumulate over a number of years, reaching levels that could cause problems.

The Gadsden Water Works, which draws from the Coosa for its source water near the sampling location, has installed a large-scale reverse-osmosis filter to remove PFAS from its drinking water before reaching its customers.

The Gadsden system was one of eight drinking water systems in Alabama that were informed in 2016 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that their drinking water contained potentially unsafe levels of the PFAS chemicals. All those systems, including Gadsden, installed specialized filters or changed their source water in order to reduce the PFAS concentrations of their drinking water below the advisory level.

Gadsden Water Works recently settled a lawsuit with industrial carpet manufacturers and other industries it believes are responsible for the chemicals in the river seeking to force them to pay for the new upgraded filtration system. The terms of the settlement were not disclosed.

Overton said that these large-scale reverse-osmosis filters are usually seen as the best option for water systems to remove PFAS from their drinking water, but there are options for homeowners as well.

“From an individual household level, having a granulated active carbon filter is a way that someone could ensure that they’re removing as much of the PFAS as possible from their own drinking water,” Overton said.

The Waterkeeper Alliance sampling program was organized as the nation tries to determine the consequences of having these chemicals so prevalent in the environment.

The EPA’s health advisory threshold is only a warning sent to drinking water systems. There is no direct requirement to limit the concentrations of PFAS in drinking water, nor is there a limit on the amount that can be discharged into public waterways.

The EPA is expected to announce a PFAS drinking water standard next year, and groups like the Waterkeeper Alliance are urging Congress to pass the Clean Water Standards for PFAS 2.0 Act, which would establish limits on PFAS discharges for industries.

“When we began testing waterways for PFAS earlier this year, we knew that our country had a significant PFAS problem, but these findings confirm that was an understatement,” Waterkeeper Alliance CEO Marc Yaggi said in a news release announcing the results. “This is a widespread public health and environmental crisis that must be addressed immediately by Congress and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).”