Can a city council in Alabama regulate its police?

Can a city council regulate its own police department?

It’s an overriding question Mobile officials will spend the first part of 2024 trying to answer, and one that could loom large over policing concerns continuing in cities throughout Alabama.

The Mobile City Council, comprising of seven elected members, is contemplating a vote on two ordinances, both which address police policy on the release of body camera footage and prohibiting no-knock warrants and pre-dawn raids.

Supporters of the ordinances say they do not go above and beyond an existing state law regulating body cam footage or a policy adopted last month by Mayor Sandy Stimpson’s office calling for an end on most pre-dawn raids.

Opponents, including the Police Department, say the council has no authority to pass ordinances telling police what to do.

“We create ordinance and policy,” said Mobile City Councilman Cory Penn. “But now the concern is that in creating ordinances and policies (addressing policing), could we be arrested for creating the ordinance? That’s a major concern.”

Said Councilman William Carroll, “I think the council’s strength is in its legislative ability. It’s our job to produce policy and it’s up to public safety departments to produce procedures to uphold the law.”

State power

The issue is also likely to put Alabama’s lack of home rule authority back into the forefront as city governments continue to contend over the frustration of having authority centralized in the halls of state power.

Alabama is one of only nine states whose constitutions do not directly delegate police power to local governments. Alabama’s Constitution was written 123 years ago. Alabama is considered a “Dillion’s Rule,” state, which means local governments are limited to the powers granted to them by the Legislature.

Politically in Alabama, the lack of home rule authority gives an enormous amount of governing power on criminal justice matters to Republicans, who at this time control all levers of state power and hold supermajority status in the Legislature.

That issue is at the heart of a debate over body camera footage access in Mobile and Decatur, two cities where a police-involved killing of a Black man this year is roiling activists and concerned citizens.

State lawmakers approved a new law that provides a guidance on the release of body camera footage but does not require law enforcement to state a reason for denying requests to view the footages. The law also does not require body cam footage to be released publicly.

The two cases that have consumed the two cities include:

Bishop William Barber II, president and senior lecturer of Repairers of the Breach, was joined by members of Jawan Dallas’ family and their attorneys, for an emergency community meeting on Thursday, Nov. 30, 2023, at All Saints Episcopal Church in Mobile, Ala. The meeting’s purpose was to demand justice and call for action in the aftermath of devastating details surfacing of late about Dallas’ death after a fatal encounter with Mobile police on July 2, 2023. Attorneys and Dallas’ family members got to watch the police-worn body cam footage of Dallas’ death, and claimed that the 36-year-old Mobile man was brutally killed by police officers.John Sharp/[email protected]

- In Mobile, the family of Jawan Dallas pleaded for over four months to view the police-worn body cam footage of his death during an altercation with two police officers on July 2. The family was repeatedly denied access, with authorities citing an ongoing investigation before a grand jury. The family eventually got to watch the footage after the investigation was completed, and authorities announced no charges would be assessed to the officers who have since returned to street patrols. The family’s attorneys, who also watched the video, have since compared Dallas’ treatment by police with George Floyd, whose death by a white police officer in Minneapolis stirred nationwide protests against racial injustice and police brutality in 2020.

People march along Lee Street in downtown Decatur, Ala., Friday, Oct. 6, 2023, during a protest against the killing of Steve Perkins by police a week earlier. (Jeronimo Nisa/The Decatur Daily via AP)AP

- In Decatur, the family of Steven Perkins was formally denied a request by the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency to view the body cam footage from a Sept. 29 shooting by police. The agency cited an ongoing investigation. But earlier this month, Mayor Tab Bowling fired three police officers and placed one on administrative leave; all connected to the deadly encounter with Perkins. The three officers have since appealed Bowling’s decision.

Handcuffing councils

Mobile City Council President C.J. Small speaks during the Mobile City Council meeting on Tuesday, Nov. 28, 2023, at Government Plaza in downtown Mobile, Ala. The meeting featured impassioned remarks from residents over the future of policing in Mobile less than one week after attorneys for the Jawan Dallas family spoke about what they saw from the video of a police-worn body camera. The family’s attorney has likened Dallas’ death to George Floyd in 2020 in Minneapolis. Dallas died that day after his encounter with police, and family members and supporters have since called for the release of police-worn body camera footage.John Sharp/[email protected]

In both cities, council meetings have been dominated by residents demanding immediate action.

But aside a politically risky move of cutting police budgets, what can the city councils do?

The councils, at times, appear to be handcuffed in coming up with a solution.

Decatur City Councilman Carlton McMasters said there is little his city can do to pass ordinances regulating police, adding “it’s my understanding that is dictated by state and federal law.”

The Decatur council is looking at one ordinance related to the Perkins case that would ban nighttime vehicle repossessions. A repossession effort led to the police shooting and killing Perkins.

“Our legal department has been researching municipal ordinances across the country to see if that is feasible,” McMasters said. “If enacting an ordinance isn’t feasible, that would be a good example of where we discuss with our PD to enact a policy.”

In Mobile, City Attorney Ricardo Woods is recommending the council forward the proposed policing ordinances to Attorney General Steve Marshall to consider, and to ensure they do not violate a state law from 1985 that created the city’s current form of government – otherwise known as the “Zoghby Act.”

Some council members are concerned with Marshall’s involvement, citing political aspirations. Council President C.J. Small said on Tuesday that he would prefer a judge weigh in on whether the council has the authority to pass ordinances addressing police policy.

Robert Clopton, president of the Mobile County NAACP, speaks during the Faith in Action Alabama Mobile Hub gathering on Monday, April 17, 2023, at Mt Zion Primitive Baptist Church in Mobile, Ala. Th meeting was held to discuss strategies toward action in ending gun violence in Mobile, and to seek action in attaining justice following the policing shooting death of 25-year-old Kordell Jones on March 7, 2023. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Robert Clopton, the head of the Mobile chapter of the NAACP, said he does not like the idea of state politics getting involved in a Mobile matter.

“I feel as if it goes out of Mobile, and if they sent this up to Montgomery for guidance and approval, it will be shot down,” Clopton said. “The more things change, the more they stay the same sometimes.”

The Zoghby Act gives the council legislative ability to set policy, but also limits how much authority elected officials have over subordinates of the mayor’s administration. The police department falls under the mayor’s purview.

Carroll said he doesn’t believe the council is overstepping its authority, saying that they are not attempting to tinker with police procedure.

Councilwoman Gina Gregory sees things differently. She said during a recent council meeting that she felt the two ordinances were unlawful and urged the council to table consideration of them until Marshall’s office had a chance to review.

“I can’t recall any ordinances the council passed or attempted to pass to regulate any day-to-day operations of a city department,” said Gregory, who has been on the council for 17 years. “I don’t know what other cities do, but our form of government is set up under the Zoghby Law and it makes us a litter different than other cities our size.”

Home rule

Mobile and Decatur aside, the issue about how far city councils can go in directing policing matters strikes at the heart of criminal justice reform measures destined to be heard during the spring legislative session starting in February.

One issue headed for likely hearing in the Alabama Legislature is whether to make body cam footage a public record. The Alabama State Supreme Court ruled via an 8-1 decision in 2021 that the footage is exempt from the state’s open records law.

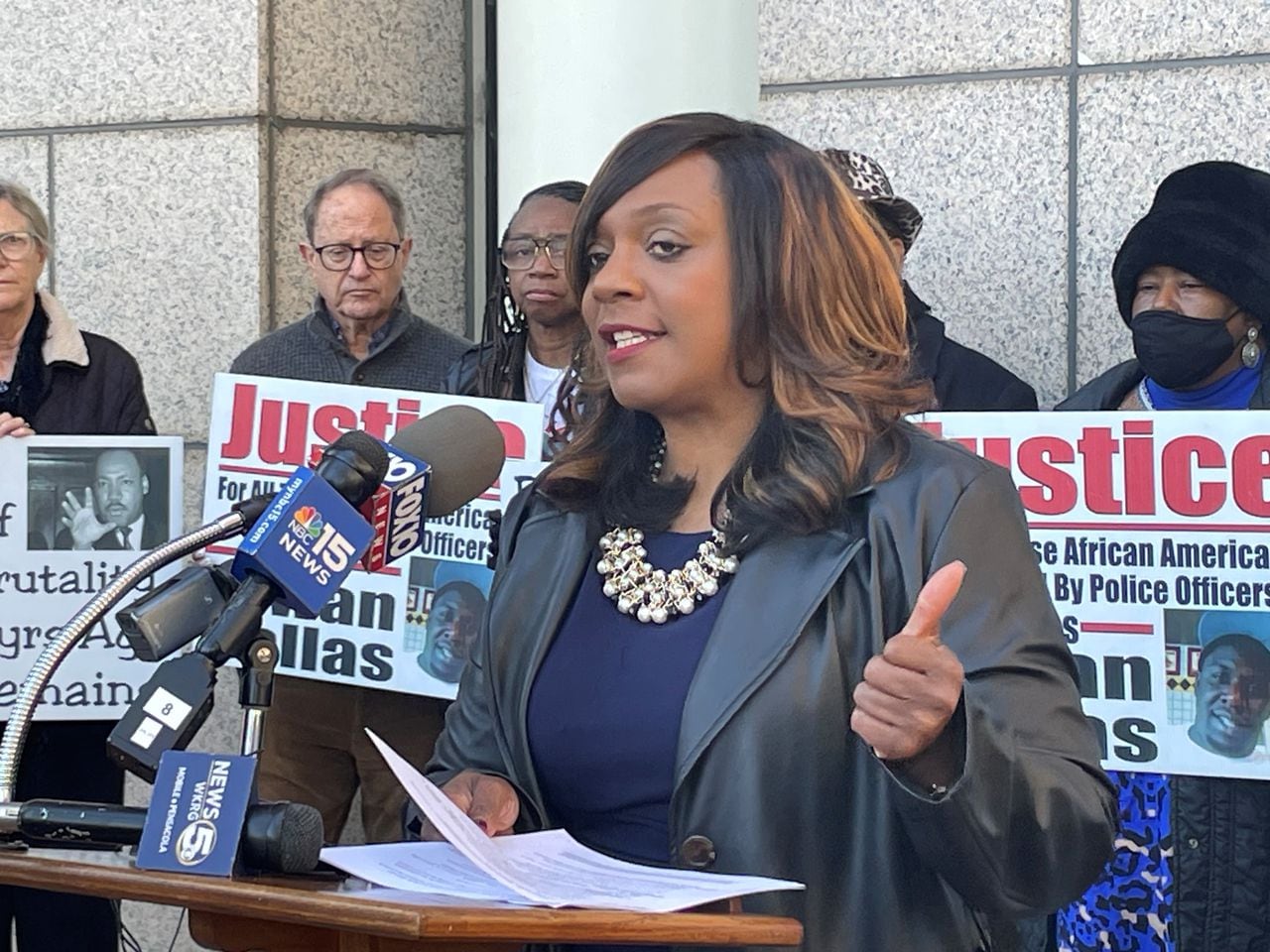

Alabama State Senator Merika Coleman, D-Birmingham, is flanked by supporters of the Jawan Dallas family as she introduces proposed legislation requesting that police-worn body camera and dash cam video footage be considered a public record in the State of Alabama during a news conference on Thursday, Dec. 21, 2023, in downtown Mobile, Ala.John Sharp/[email protected]

Alabama State Senator Merika Coleman, D-Birmingham, who is sponsoring legislation requiring the footage to be public record, said there is nothing the cities can do about making substantive changes, referring to the lack of home rule authority cities have in Alabama.

“I often tell young people when talking to them … I say that you are looking at a very powerful woman,” said Coleman, who is also a candidate for the 2nd congressional district seat in 2024. “I say that because the power (in Alabama) is centralized in Montgomery.”

She added, “We don’t have home rule in Alabama, that’s why many of the city officials don’t have the ability to pass (criminal justice reform measures). They will be passing them in name only just to say this is something we want in our city.”

It’s not always so clear cut. In Huntsville, the City Council adopted an ordinance in October that goes above and beyond a state law adopted a year ago prohibiting people to hold their cell phones while driving. The state law considers it a secondary offense, but Huntsville lawmakers OK’d a provision – backed by their police department – that makes it a primary offense and gives police more authority in regulating it.

“It will be interesting to see if it’s contested,” said former Republican state Rep. Mike Ball of Madison, a former Alabama State Trooper.

Ball said he was unaware of any city council adopting an ordinance directing police on a specific policy that the agency might oppose.

He doesn’t believe a council is overstepping its authority in doing so.

“(A city council) doesn’t have the authority over the State Police or the local sheriff, but the police department is under the city government,” Ball said. “I know police officers feel like this hampers them and their ability to do the job, but their power is derived from the local government they work for. They can argue it hampers their ability to enforce laws, but the city council is the one who answers to a vote of the people they represent. That’s called a representative republic.”

Alabama State Rep. Allen Treadaway, R-Morris, and a former assistant police chief with the Birmingham Police Department, speaks on the floor of the Alabama House of Representatives on Thursday, June 1, 2023, in defense of legislation that adds enhanced penalties against people who commit crimes while associated with a criminal enterprise. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

State Rep. Allen Treadaway, R-Birmingham, who served over 30 years in law enforcement, also said he cannot recall one instance in Alabama in which a city council voted to adopt an ordinance that established a policing policy.

“I don’t know of any case where a council passed anything that has had an effect on a police department or an oversight of a police department’s policies and procedures,” said Treadaway, the current chairman of the Alabama State House’s Public Safety and Homeland Security Committee.

But Treadaway said he would have a concern with city councils adopting permanent ordinances regulating policing, such as whether to release body cam footage.

Mobile is also contemplating permanent ordinances restricting the use of pre-dawn raids or no-knock warrants. The ordinances codify into city law the order Stimpson made in November following a pre-dawn raid that resulted in a police officer killing a 16-year-old boy who was not the intended target of the raid.

“I just think when you have elected officials who come and go, we have to be careful with emotions when a tragedy occurs in a community that they somehow want to mandate changes to procedures,” Treadaway said. “There needs to be more listening and understanding on their point as to why there are procedures and policies in place as to body worn cameras and if the (footage is) released, how that might affect a criminal who is on the loose or eventually when they are brought to trial. We have to be careful about that.”

Matthew Valasik, associate professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Alabama, said police generally do not like being scrutinized, and that reform measures often take a long time to implement.

“Historically, police departments are out of the purview of the public and generally, when there is a reform of any kind, it takes them a while to adapt to it,” Valasik said. “You really need everyone moving in the same direction. If one of those institutions isn’t, then it becomes a challenge.”

Disproportionate statistics

Decatur Police officers politely ask protestors to leave the median and move to the sidewalk for their own safety as a crowd gathers along Wilson Street in front of the Doubletree by Hilton hotel in Decatur, Ala., Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2023, to protest the killing of Stephen Clay Perkins by a Decatur police officer last week. Alabama governor Kay Ivey was speaking at an event in the hotel. (Jeronimo Nisa/The Decatur Daily via AP)AP

The differing viewpoints on policing authority could be headed to a classic urban-vs.-rural debate in Alabama, with racial undertones where a mostly white GOP that runs state government and has the power to preempt local ordinances in cities that are majority Black, and where Black residents continue to deal disproportionately with violent encounters with police.

According to a Washington Post database, police killed 1,096 people in 2022. It was the highest number of deaths of people by police in a single year since the Washington Post began tracking the data in 2015.

The 2023 figure is closing into 2022′s high number, with 1,089 deaths.

Black Americans, who account for 14% of the U.S. population, are killed more than twice the rate by police than white Americans, according to the Post.

Mobile has been a majority Black city for quite some time, with a majority Black voting-age population even after a July 18 annexation vote that brought in more white voters.

There have been several high-profile violent encounters involving Black men and police in 2024, fueling the concerns in Alabama’s Port City and the spirited commentary at council meetings.

Council members hope what they do next isn’t viewed as a challenge against police officers, even though 50 uniformed police showed up to a recent meeting to oppose the ordinances.

“I think you are going to have your challenging moments,” Penn said. “But even with the ordinances that are presented, it’s nothing against police officers. It’s not an attack. I think they are supportive and helpful toward protecting the officers. So hopefully people can see that.”