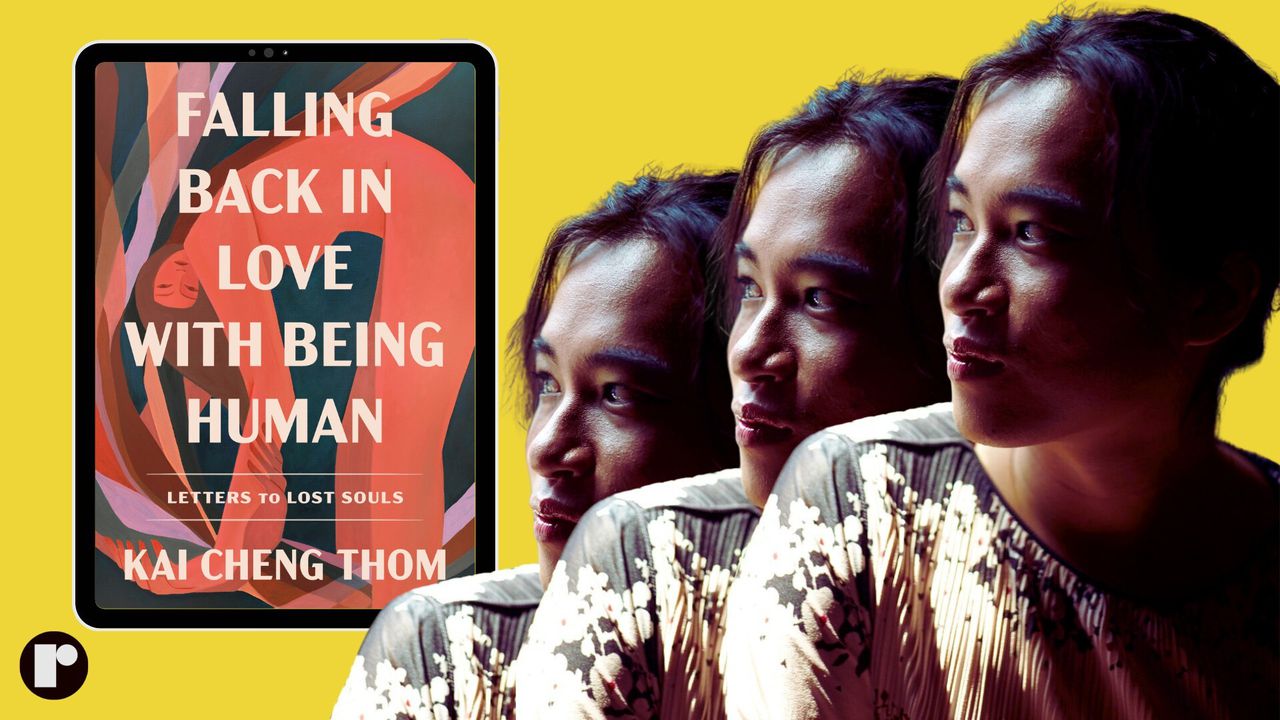

Breaking the chains of self-hate: trans author Kai Cheng Thomâs message to queers and lost souls

Kai Cheng Thom defines a lost soul in two ways: her own lost soul, but also the lost soul of the world at large.

Thom is a Chinese Canadian writer, performance artist, community healer, a former queer youth therapist and advice columnist at LGBTQ digital publication Xtra Magazine. Her newest poetry collection, Falling Back in Love with Being Human: Letters to Lost Souls, is a series of letters that serve as a warm invitation for what she considers to be “lost souls” of which she is not excluded from.

“I’m an Asian trans lady—there’s nowhere to go,” said Thom, who in the process of writing the book turned inward first. “That invokes some lostness. There are actually real life-threatening agendas we are being threatened with every day.”

One of the poems is a letter to J.K. Rowling, inspired after the Harry Potter author released a statement in June 2020 defending her personal distaste in the fight for trans rights. Thom’s connection wasn’t in her disagreements with Rowling, though.

An excerpt from her letter read: I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe. When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman, then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside.

“There’s a lot in the statement to disagree with, but the parts that I focused on were moments where she talked about being a survivor of abuse, and about being kind of gender confused as an adolescent,” Thom said, noting that people like Rowling are the other group of people who Thom categorizes as a lost soul. “She is someone who, from a place of pain, reacted in fearful ways and then that fear became a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

In the opening of the book, Thom writes about the heartbreak, violence, and the losses she witnessed in the world, and how they inspired her to write poems in the form of letters.

“Yes, dear reader,” she says in the first few pages. “This is a book of love letters—to everyone and everything I have ever had trouble holding in my heart.” The poetic formatting of letters is not coincidental. Thom admits to Reckon that she loves the epistolary format, though the significance runs deeper than her own personal enjoyment.

“There’s something categorically different about writing to “you,” because it implies that there is a direct relationship between the writer and the reader,” she explains. “I think we need that closeness and intimacy to really explore the emotional landscape of all the conflicts and polarization happening in the world.”

Given the record-breaking number of anti-trans legislation this year and recent hate crimes against Asian women, Thom had to reconcile with her own rage. For her, falling back in love with being human means falling back in love with her rage. She describes it as a deep monstrous part of herself that actually wants revenge.

“I think that if we stay stuck in either the place of repressing rage or like the place of constantly enacting rage, we become mirrors of the people who are trying to hurt us,” she said. It is no surprise that she is unafraid of confronting the people who have hurt her—people whom she might have rage toward.

In her chapter “To the Johns,” Thom speaks directly to the men who would frequently see her when she was a sex worker. In the beginning of the chapter, she lays out the bad deeds her former clients committed, like ghosting appointments or demanding more out of her without additional pay. In the second half of the chapter, she shifts to reflect on the men who treated her well, ultimately challenging the simplistic notion that men who seek sex workers are inherently deviant or cruel—even if some of them were.

“Being a sex worker taught me something about humanity, and particularly men, like nothing else did—not being a therapist, not being a social worker,” she explains. “There’s all this whorephobia about sex workers, but there’s also this idea about “Johns” like they’re disgusting, horrible people.”

Even while she straddles her frustrations with some of the men, she gives them grace in the same vein. She says that in sex work, men would be a lot more decent and vulnerable because they knew they were paying for brevity and anonymity “so they could release the squirmy, soft parts of themselves.”

This experience taught Thom about empathy, “that inside people who we deem as monsters were almost always somebody just looking for a space to be taken care of,” she said.

Her writing process also took on a journey of its own in tandem with her emotional growth. In her twenties, she would go on bad dates with men, pick up McDonald’s on her way home and write from a place of self-loathing. Sometimes intentionally. This was her practice of summoning her “monster,” agitating it for the sake of seeing it be upset. For her, “monster” is another way of describing the pain she carries, and her craft as a writer in her twenties relied on pain to be the catalyst for her art.

Thom, who is now in her thirties, said that now it is “much more about creating a ritual time for the monsters inside me to emerge, and then to play with them. To be in a loving relationship with the parts of me that are unsettled that have something to say. It’s a very spiritual experience.”

It was also intense to confront moments in her past that she struggles to relive. In the chapter “To the ones who hurt me,” she repeats the phrase “I forgive you” over and over for three pages. It was an ode to the bystanders who watched her be assaulted when she was in her twenties.

At the time, Thom was heavily embedded in a queer anarchist community in a major city. “We were obsessed with the rhetoric of safety, safer space, harm reduction, consent, and were talking about it nonstop,” she said. “But then we would have these intense queer parties, and there were a couple particular incidents where I was assaulted. People I knew were in the room and didn’t do anything. It made me wonder: Why? What was it about me and the relative worth or worthlessness of my life? Or was it just hypocrisy? That was hard to forgive.”

Besides the series of things and people she addresses in the book, she wants to make it clear who this book is for. On one hand, she dedicates the book to the queers who hate themselves.

“Whether we committed, witnessed or experienced violence, no one should have to hate themselves,” said Thom, who also dedicates this book to “my younger self who lived in an art-barren neighborhood. I lived in a place where access to poetry was not easy. And it’s my hope that teenagers could find this book in a Target and see themselves in a deeply nuanced and complex way.”

Ultimately, the heart of Falling Back in Love with Being Human is in the introduction to the series of letters, where Thom begs the question: What happens when we imagine loving the people—and the parts of ourselves—that we do not believe are worthy of love?

For her, this book is the answer to that theory. “I think life becomes more worth living.”