Birmingham and the NFL, Part 4: One last shot, moving on

EDITOR’S NOTE: The second iteration of the Birmingham Stallions won the championship of the United States Football League on July 1. The new USFL is the latest in a long line of upstart football leagues to call the Magic City home in the last five decades. None has lasted longer than three seasons. From the mid-1960s to the late 1990s, Birmingham also at various times pursued a franchise in the National Football League, but was never able to land either an expansion team or a team relocated from another city. The following story is the last in a series that traces the history of pursuits by local leaders to land a big-league football team for Birmingham.

Paul Finebaum began getting calls about the subject in the mid-1980s — could, should Birmingham, which called itself the “Football Capital of the South,” build a domed stadium to try and woo an NFL team?

Such plans in other cities had been a mixed bag in the past. While Atlanta landed baseball’s Braves and the NFL’s Falcons shortly after building what would become Atlanta Fulton County Stadium in the mid-1960s, the Sun Coast Dome in St. Petersburg, Fla., sat empty for years while several Major League Baseball teams threatened to move there before securing stadium deals in their home cities.

But by the mid-1980s, Birmingham’s Legion Field was no longer considered state-of-the-art. It was sufficient for a handful of Alabama and Auburn games per year, but as the permanent home base of an NFL team, the “Old Gray Lady of Graymont Avenue” left a lot to be desired.

READ THE FIRST THREE PARTS IN THE SERIES

Part 1: ‘Close enough, almost, to touch’

Part 2: Rival leagues, rampant rumors, and Dolphins

Part 3: One very powerful man’s opinion, another start-up league

Those early calls to Finebaum, by the mid-1980s a highly influential columnist at the Birmingham Post-Herald, came from a man named Art Clarkson. Clarkson himself was very prominent in Birmingham sports, having brought the Barons minor-league baseball team back to the city after six-year absence in 1981 and later reviving the Bulls hockey club.

“Art started banging the drum for the domed stadium very early on,” Finebaum recalled. “He very effectively co-opted me as his trumpet. I started writing in the mid-80s about the dome, with Art being the one talking about Legion Field being a relic.”

The Barons played at Rickwood Field until 1988, when they moved into Hoover Metropolitan Stadium in the suburbs. Rickwood sat less than two miles from Legion Field in west Birmingham, a neighborhood that began to deteriorate due to white flight once public schools were integrated in the late 1960s.

In addition to Alabama and Auburn — who played the annual Iron Bowl there every year until 1989 — Legion Field had been the home to every Birmingham pro football team over the years. The Americans and Vulcans of the World Football League played there in 1974 and 1975, as did the Stallions of the original United States Football League from 1983-85.

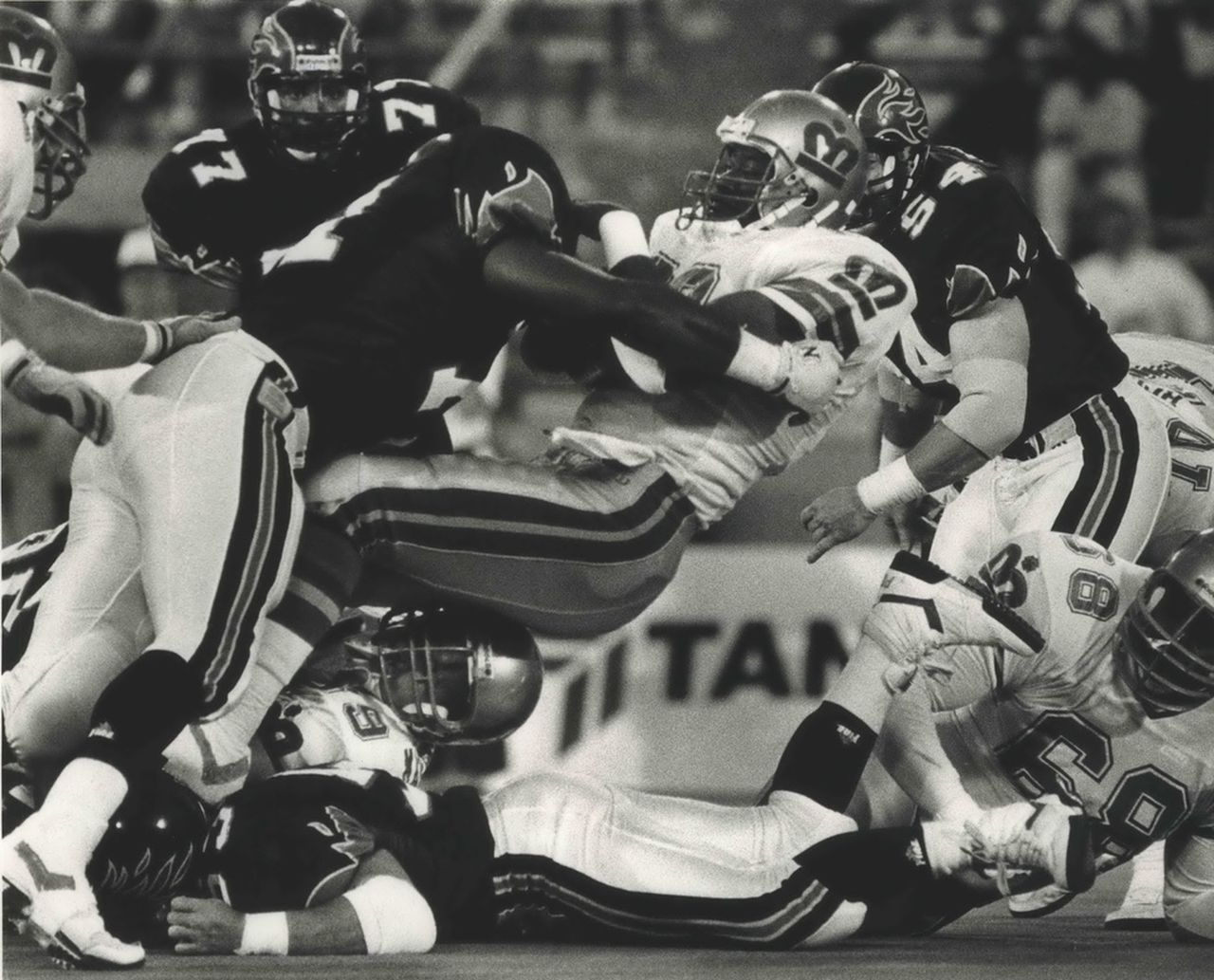

The Birmingham Fire of the World League of American Football is shown during a game against the London Monarchs at Legion Field in Birmingham in 1991. The Fire lasted two seasons before the league re-packaged itself as NFL Europe and moved the entire operation overseas in 1993. (Photo by Joe Songer/Birmingham News)The Birmingham News

Another pro football venture set up in town in 1991, with the Birmingham Fire one of 10 teams in the World League of American Football, which featured three teams in Europe and one Canada in addition to seven in the U.S. The WLAF wasn’t as high a level of football as the WFL or USFL had been, but it did have the financial backing of the NFL.

NFL executives viewed the WLAF less as a way to develop players (colleges did that for free, after all) than as a chance to “test” markets for potential future expansion, particularly London and San Antonio. Then-commissioner Paul Tagliabue made visits to all the WLAF home cities in 1992 and stopped short of showing any support for Birmingham’s potential NFL future.

Tagliabue noted that 11 cities applied for NFL franchises when the league announced expansion plans in 1990, but Birmingham wasn’t one of them.

“At this point, that’s probably a sound judgment,” Tagliabue said.

Scott Adamson, then a young sportswriter who would later be sports editor of the Post-Herald, had long dreamed of a major pro football team for his hometown. He found Tagliabue’s remarks discouraging, to say the least.

“He basically said at that point that Birmingham was just a better fit for the World League instead of the NFL,” Adamson recalled in 2020. “So that was almost like ‘thanks for playing, but you’re not major-league.’ That was sort of the end of it. ‘It’s a nice city, but it’s not nice enough to get an NFL franchise.’”

The World League proved to be something of a red herring anyway, as none of the 10 home markets in the league has ever gotten an NFL team. After two seasons, the NFL disbanded the American portion of the WLAF and re-purposed it as NFL Europe, a developmental outfit that played games exclusively in the U.K., Germany and Spain until ceasing operations in 2007.

The NFL expanded to Charlotte (the Carolina Panthers) and Jacksonville (the Jaguars) in 1995, further appalling long-time football followers in Birmingham who had seen those two cities — among others — surpass their hometown in population, business development and prestige in the last half-century. So, if there was any hope of an NFL team in Birmingham, it would have to be a relocation rather than an expansion.

Birmingham did have one fairly major flirtation with an NFL team in the mid-1990s, but it was as the result of the Houston Oilers moving to Nashville (another Southern city once viewed as “inferior” to Birmingham). Oilers owner Bud Adams had announced in 1995 his team would move to Nashville for the 1998 season, causing support in Houston to disappear almost immediately.

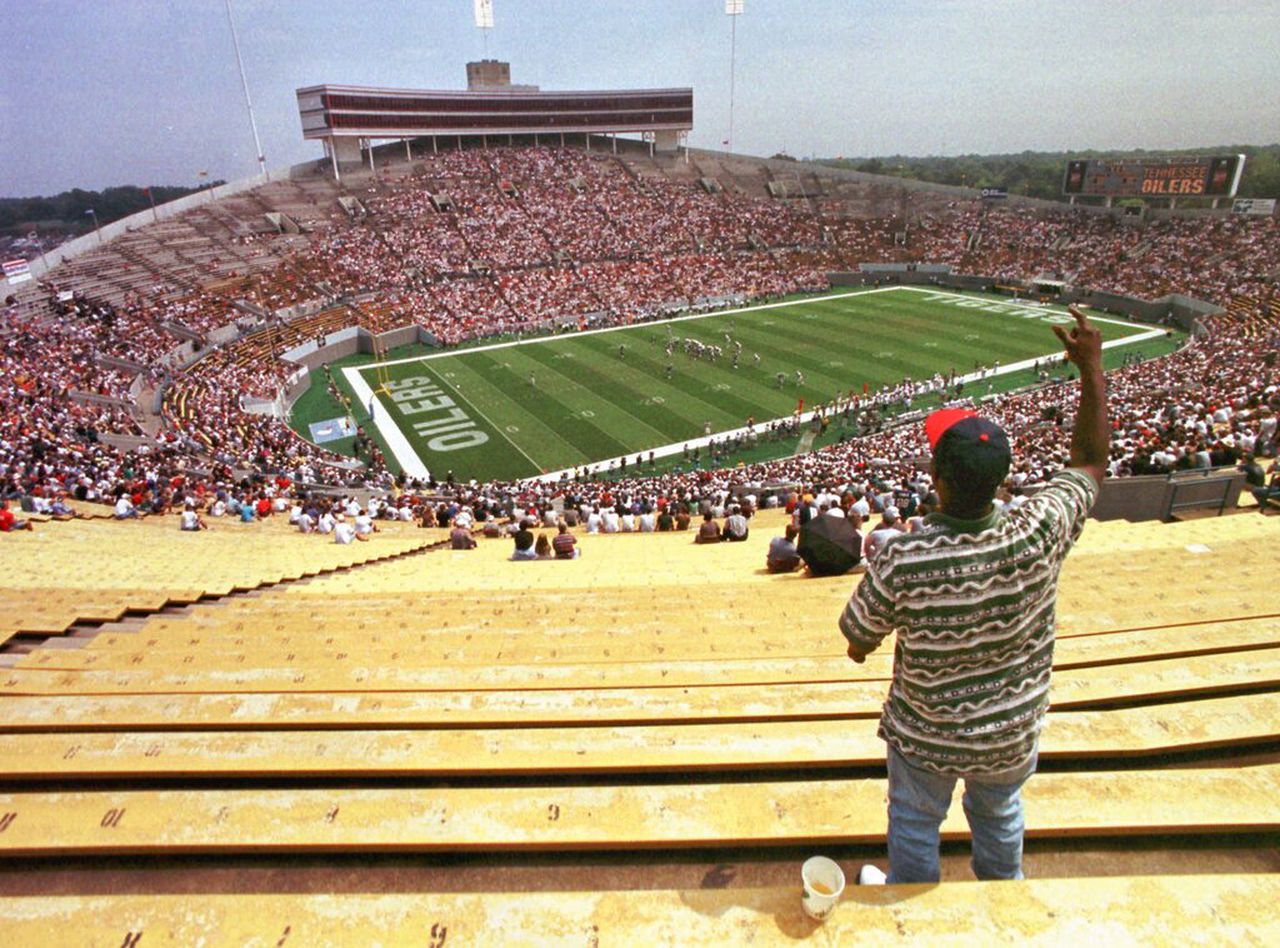

The Tennessee Oilers play their opening game against the Oakland Raiders before a sparse crowd of 30,000-plus at Liberty Bowl Stadium in Memphis on Aug. 31, 1997. The team spent just one season in Memphis before moving permanently to Nashville in 1998. (AP Photo/Jake Herrle)AP

With a new stadium in Tennessee still two years away, the Oilers were looking for a temporary home to play the 1997 and 1998 seasons. Birmingham made a run at it, proposing a preseason game at Legion Field as a test.

“We had several meetings with the then-Houston Oilers’ administration, to the point of probably thinking they were going to come maybe even temporarily to Birmingham,” said Walter Garrett, stadium manager at Legion Field from 1968-2005. “Instead they ended up going to Nashville. …That was what I thought was closest we had gotten to the possibility of getting a pro team.”

The Oilers actually played the 1997 season in Memphis at the Liberty Bowl but had perhaps underestimated the rivalry between that city and Nashville in doing so. Due to low attendance, the team (by then re-christened the Titans) played at Vanderbilt Stadium in Nashville in 1998 before what is now Nissan Stadium opened the following year.

The dalliance with the Oilers played out in late 1996, just as the Birmingham Post-Herald published a cover story “Tale of Two Cities” comparing the ever-growing Nashville with the stagnant Birmingham. Nashville had a combined city and county government, allowing for proposals such as the plan to build Nissan Stadium and what is now Bridgestone Arena (home to the SEC basketball tournament and the NHL’s Nashville Predators) to pass more easily.

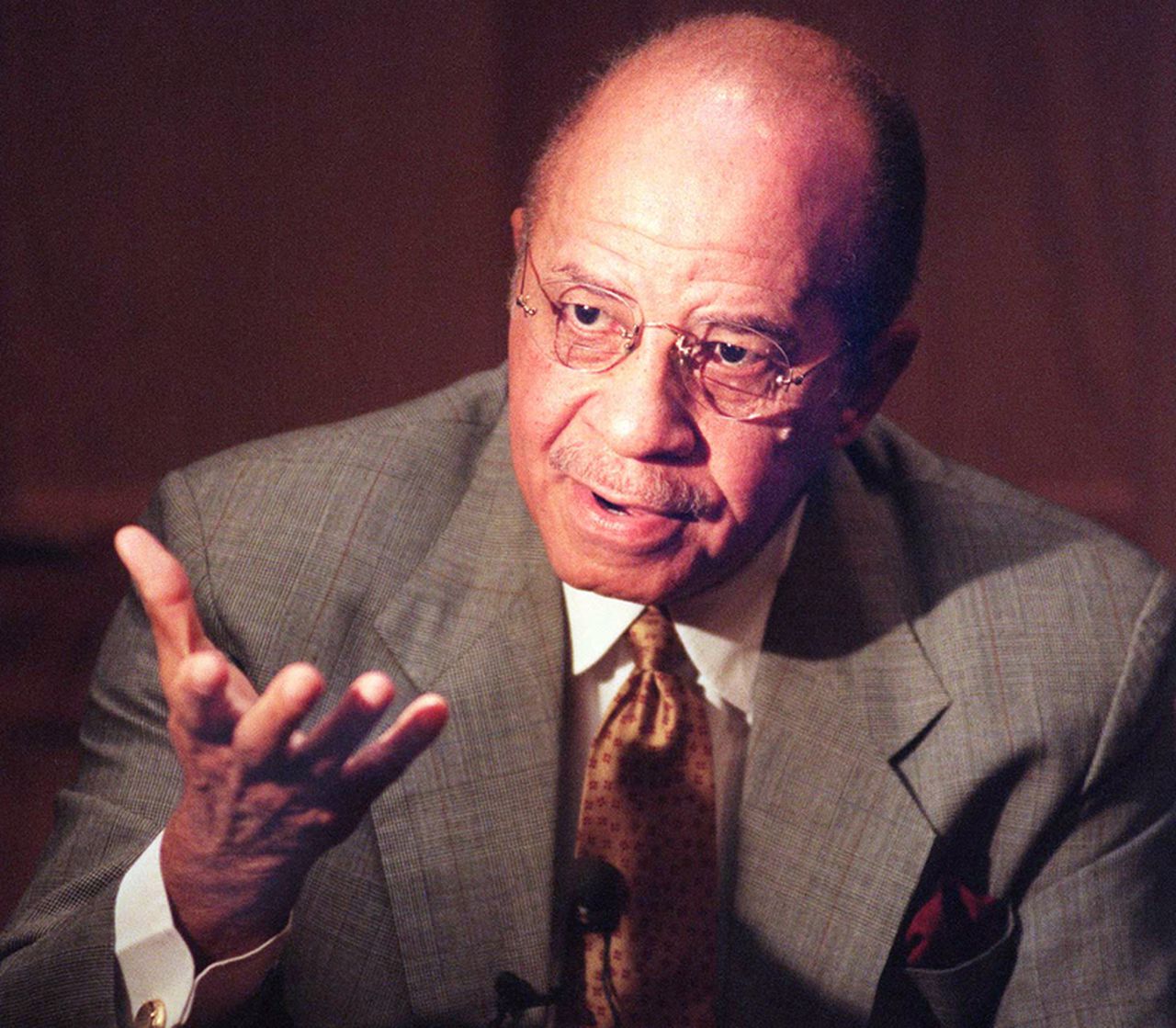

“We just do not have a real sense of community like Davidson County (Nashville), Charlotte, Jacksonville,” then-Birmingham mayor Richard Arrington said in the story. “Those governments speak with one voice. Here, we speak with different voices. All the facilities we have here — the Botanical Gardens, the zoo — suffer, because we don’t have a united effort. Somehow, there has to be some formalized system of inter-governmental cooperation.”

A year earlier, Alabama Rep. John Rogers had proposed a bill for a domed stadium, with support from Clarkson and others of influence in Birmingham. Clarkson envisioned something similar to Atlanta’s 71,000-seat Georgia Dome, which had opened in 1992 at a cost of $214 million and not only housed the NFL’s Falcons but had taken the SEC football championship game from Legion Field beginning in 1994 and hosted several events at the 1996 Summer Olympics — including basketball and gymnastics simultaneously.

Art Clarkson, who owned the Birmingham Bulls, Birmingham Barons and Tennessee Valley Vipers at one time or another, is shown in 2002. Clarkson was a proponent of a domed stadium for Birmingham, which he hoped would lure an NFL team to town. (Huntsville Times file photo by Eric Schultz)HVT

The thinking, at least among some, was that a domed stadium might finally lead to an NFL team for Birmingham. Both Clarkson and Gene Hallman, a longtime sports promoter and marketer in Birmingham, were hopeful.

“If you would have gone to the average person on the street 10 years ago in Jacksonville or Nashville and asked them if they would have had an NFL team in 10 years, an overwhelming majority would have said no,” Hallman said. “We’re very similar to those cities and we need to be forward-thinking.”

Another major figure who emerged on the Birmingham sports scene around this time was HealthSouth CEO Richard Scrushy, who was viewed as a potential owner for any future pro sports team in the city. Scrushy was also a major booster of the domed-stadium plan.

(As it turned out, Scrushy’s wealth via HealthSouth ended up being wildly overstated. He was later convicted on federal charges of financial impropriety and ended up in prison in a scandal that also ensnared former Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman.)

Rogers’ proposal wound up becoming MAPS, the Metropolitan Area Projects Strategy. MAPS proposed a $525 million sale of bonds to be paid off by an increase in local hotel sales taxes and would result in various transportation and infrastructure upgrades in Birmingham, as well as a domed stadium/convention center.

MAPS was put to a vote on Aug. 4, 1998, and turnout in Birmingham was the largest since the 1992 presidential election. The proposal failed by a 57-43 margin, with most of the “no” votes coming from the suburbs.

“It was attacked from all over,” Finebaum said of MAPS. “But had it passed, Birmingham would have had a domed stadium by around 2000. Of course, it would be obsolete by now.”

While the MAPS plan was being formulated, Birmingham again came up in relation to an NFL team that was threatening to move. The Minnesota Vikings battled local government over their lease in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, which they’d occupied since the early 1980s.

Richard Arrington, mayor of Birmingham from 1979-99, tried to get the MAPS proposal passed in 1998. The project would have improved infrastructure throughout the city, and provided for the building of a domed stadium/convention center. The vote failed by a significant margin, with most of the “no” votes coming from suburban Birmingham. (Birmingham News file photo by Phillip Holman)PH

The Vikings were also for sale, and famed spy-novel author Tom Clancy had withdrawn his $200 million bid in May 1998 over fears his ongoing divorce proceedings would adversely affect his financial portfolio. Former team president Roger Headrick put together an ownership group that included Dr. Larry Lemak, a well-known orthopedic surgeon in Birmingham.

The Headrick group initially lost out on the Vikings to San Antonio-based businessman Red McCombs, who quickly put to rest any chance of the Vikings moving. Lemak also never intimated the idea of moving the team to Birmingham, saying he viewed the Vikings an “investment opportunity.”

Even if MAPS had passed, Hallman says now he’s not sure it would have resulted in the Vikings or any other NFL team coming to Birmingham. Building a stadium to lure an NFL team is a classic example of putting the cart before the horse, he said.

“If you’re able to find a franchise that’s willing to relocate, they’re going to want input into the facility,” said Hallman, who now runs Eventive Sports. “They’re going to want to direct the design and make sure that it’s state-of-the-art for that period of time. And there will be an expectation that they contribute financially to the facility.

“So (MAPS) was really being done because (A) we needed to replace Legion Field, desperately, and (B) we needed more convention floor space, which a dome gives you oddly enough. Yes, there was this periphery conversation with the Vikings, but I wouldn’t say the correlation was high, as I know now.”

Thus ended the last hint that an NFL team might move to Birmingham. The MAPS program had failed, and Legion Field had become hopelessly outdated by the turn of the century.

There were two other Legion Field pro football tenants worth mentioning — the Birmingham Barracudas in 1995 and the Birmingham Bolts in 2001. The Barracudas was part of the Canadian Football League’s ill-conceived expansion into the United States, while the Bolts were a member of the original XFL, a joint venture of NBC Sports and World Wrestling Entertainment impresario Vince McMahon.

Both played in the spring/summer and drew well in their initial stages, but local fans lost interest as college football season approached in August. The CFL pulled the plug on its U.S. venture after just one season, as did the XFL with its entire operation.

Alabama football coach Mike Shula is shown during a 2003 game vs. South Florida, the last game the Crimson Tide played at Birmingham’s Legion Field. (Birmingham News file photo by Steve Barnette)bn

Alabama and Auburn played the last Iron Bowl in Birmingham in 1998, and the Crimson Tide played its final home game there in 2003. The stadium’s west-side upper deck was condemned and removed in 2005, though UAB continued to play its home games there until 47,000-seat Protective Stadium opened in downtown Birmingham in 2021.

“The original XFL tried to pretend it wasn’t a minor league, but it certainly was,” said Adamson, who published a book in 2020 about Birmingham’s pro football history. “Everything since then I think is just sort of trying to position itself that if the NFL ever decides they want to do the NFL Europe (developmental league) route again, then they could be in line for that. If you want to have any kind of chance at survival, hitching your wagon to the NFL is the best way to go.”

To that end, the Alliance of American Football formed in 2019, billing itself as an unofficial developmental league for the NFL. The Birmingham Iron was one of the AAF’s eight teams and played its home games at Legion Field.

But the Alliance fell apart midway through its first season, when the league’s primary investor pulled out. Another Birmingham pro football league had failed, but it wouldn’t be the last to give the city a try.

The new USFL formed in 2022, with a different format than most of its predecessors. League executives — a group that includes former Dallas Cowboys star and current broadcaster Daryl “Moose” Johnston as president — secured the rights to several of the franchise names, logos and color schemes from the original USFL, putting teams such as the Pittsburgh Maulers, New Orleans Breakers and yes, the Birmingham Stallions, back on the field. (The XFL has also re-formed twice, in 2020 and 2023, but has not put a team in Birmingham either time).

The entire USFL played its games at Birmingham’s Protective Stadium in 2022 but moved to a four-city “pod” system for Year 2. Two each were based in Birmingham, Detroit, Memphis and Canton, Ohio, with the Stallions and Breakers calling the Magic City home.

Birmingham has been the class of the league in both of its seasons, going a combined 17-3 and winning the championship in both 2022 and 2023. Attendance and TV ratings were down from Year 1 to Year 2, but it appears the commitment is there to bring the USFL back for a third season.

Gene Hallman, a longtime sports promoter and marketer in Birmingham, is shown at Barber Motorsports Park in 2007. Hallman and the organizations he has worked with have helped bring numerous sports and sporting events to the city and surrounding area over the years, from football to basketball, to auto racing and soccer. (Birmingham News file photo by Matthew Williams)bn

“It all gets back to resources, and commitment,” said Hallman, whose organization has been a primary promoter of the USFL in Birmingham. “The business model for a professional football team is dramatically different than minor league baseball, or the (NBA) G-League. The economics are much more difficult, starting with medical and liability insurance. That’s just an enormous factor. And the previous leagues did not have the financial wherewithal or the long-term vision to make it work.

“This is 180 degrees opposite from the previous two I’ve been involved with. It is tracking on a solid trajectory toward success. The ratings are solid, the crowds are solid. … I’m very optimistic about this one, the USFL, being successful.”

Then there is UAB, which began playing football in 1991, moved up to the FBS level in 1996 and joined Conference USA in 1999. The Blazers found it difficult to push through entrenched Alabama and Auburn fandom in Birmingham, and never averaged 25,000 fans per home game through their first quarter-century.

UAB president Ray Watts infamously killed the football program after the 2014 season, only to see it revived three years later after widespread backlash. The Blazers averaged 26,000-plus for home games in the first three seasons at Legion Field after returning in 2017 and have averaged slightly less than 25,000 since the move downtown to Protective Stadium.

The Blazers move leagues this season, from CUSA to the American Athletic Conference. After so many failed professional football ventures, it’s possible UAB is the closest thing Birmingham will ever get to a sustained “home” team.

UAB students and fans are shown during a 2021 game against Liberty, the Blazers’ first at Protective Stadium in downtown Birmingham. (Patrick Greenfield/AL.com)

“I really have total love and respect for UAB and what they’ve done for this town,” said Tom Cosby, who worked for the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce for 35 years. “Even despite all the years I worked on the peripheries of trying to get NFL football in here, I think UAB is our ticket. From a Chamber of Commerce perspective, here in the Deep South, you’ve got to have a football team if you’re really going to grow your enrollment. When (UAB) killed football, the enrollment maybe was around 18,000. And in since they brought it back, it’s grown to 22,000.

“… As Bear Bryant famously said ‘in Alabama, it’s kind of hard to rally around a math class.’ Even though the UAB students don’t support their team the way I wish they would, the fact that it’s there gives them something. The center holds with a football team here in the Deep South. And without it, it doesn’t.”

UAB is part of a Birmingham sporting scene that still includes the Barons, who themselves moved downtown to Regions Field in 2013. The G-League’s Birmingham Squadron play basketball at Legacy Arena, the Legion FC of the United Soccer League competes at Protective Stadium, while the latest version of the Bulls hockey team calls the Pelham Civic Center home.

Birmingham also hosts a number of large-scale sporting events each year, including the Magic City Classic football game between Alabama State and Alabama A&M at Legion Field, the SEC baseball tournament in Hoover, the Regions Tradition PGA Champions Tour event at Greystone Golf and Country Club and the Children’s of Alabama IndyCar Grand Prix at Barber Motorsports Park. NCAA basketball regionals also come to town on a regular basis (with Alabama and Auburn both playing at Legacy Arena this past March), while Birmingham served as the hub for the 2022 World Games.

But in terms of a “major league” team in MLB, the NBA or the NFL, it appears that ship sailed a long time ago for Birmingham. Even Hallman, the eternal optimist and local sports booster, admits “I just don’t see.”

“I don’t see it anywhere on the horizon for a lot of different reasons,” Hallman said. “When you look at the NBA and its waiting list, it’s got five or six cities that clearly would be in front of us for relocation, or if they were to entertain an expansion, would be well in front of us. I think you could go through every league and make that case. I think even (Major League Soccer) is reaching a saturation point.

“But I don’t think we need it to validate ourselves as a sports town. We do have, of course, great intercollegiate athletics. But we also are known as a great event town. … When something comes here, that’s an event, or even in the case of the USFL, it’s going to be supported in a way that it would get buried in one of our sister cities here in the Southeast.”

Creg Stephenson has worked for AL.com since 2010 and has written about football for a variety of publications since 1994. Contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter at @CregStephenson.