Birmingham and the NFL, Part 3: One powerful manâs opinion

EDITOR’S NOTE: The second iteration of the Birmingham Stallions won the championship of the United States Football League on July 1. The new USFL is the latest in a long line of upstart football leagues to call the Magic City home in the last five decades. None has lasted longer than three seasons. From the mid-1960s to the late 1990s, Birmingham also at various times pursued a franchise in the National Football League, but was never able to land either an expansion team or a team relocated from another city. The following story is the third in a series that traces the history of pursuits by local leaders to land a big-league football team for Birmingham.

Hugh Culverhouse was a Birmingham native, nationally renowned tax attorney and a multimillionaire real estate investor, but even he wasn’t foolish enough to cross Paul “Bear” Bryant in the state of Alabama in 1981.

Culverhouse, then owner of the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers, was the guest speaker of the Birmingham Touchdown Club on Nov. 9, 1981. During the Q&A portion of the evening, he was asked about what had been on the mind of many in the self-styled “Football Capital of the South” for nearly two decades — the possibility of Birmingham getting an NFL franchise of its own.

READ THE FIRST TWO PARTS IN THE SERIES

Part 1: ‘Close enough, almost, to touch’

Part 2: Rival leagues, rampant rumors, and Dolphins

Culverhouse said he would support the idea, with one major, MAJOR caveat.

“Coach Bryant at Alabama is a very close friend,” Culverhouse said, according to the Birmingham Post Herald. “If he doesn’t want a team here, then I don’t.”

Culverhouse went on to note that the NFL planned to expand again by 1985, and that Birmingham was on the short list of possible franchisees, along with Phoenix, Los Angeles, Memphis and Jacksonville. He added that if Birmingham was serious about getting an NFL team, “the city fathers, businessmen, everybody should unite and go work for one.”

As fortune would have it, Bryant was scheduled to speak to the Birmingham Monday Morning Quarterback Club the following week. His Alabama team had just beaten Penn State 31-16, giving the legendary coach his 314th career victory and moving him into a tie with Amos Alonzo Stagg for the all-time record.

Though Bryant did discuss the upcoming Iron Bowl (which Alabama would win 28-17, giving him the record) and his team’s possible bowl destination, he focused largely on Birmingham’s pro football potential — which he staunchly opposed.

“If you want pro football, you don’t want college football,” Bryant said, via The Birmingham News. “I don’t want to see it in Birmingham. A lot of people want pro football in Birmingham. I’m not one of them.”

It’s not as if Bryant was anti-NFL, per se. He’d famously toyed with the idea of leaving Alabama for the Miami Dolphins in the winter of 1969-70, and by the early 1980s had dozens of former assistant coaches and players making careers in the pro game.

But he wasn’t about to voluntarily cede territory — along with eyeballs and pocketbooks — to pro football. Moreover, he believed it would harm college football in Alabama on the whole.

“If you have (pro football in Birmingham), Jacksonville, Troy, Livingston, Florence and Alabama A&M will be out of business,” Bryant argued. “Five or six years later, Alabama and Auburn will be playing before 25,000.

“If you want pro football in Birmingham, turn on the tube.”

Hugh Culverhouse, right, a Birmingham native who owned the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, advocated an NFL team for his home city, but only if Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant was in favor of it. (Allen Dean Steele/Allsport via Getty Images)Getty Images

Bryant worried that the presence of an NFL team would diminish college football in Birmingham, the way he believed that Falcons had undercut Georgia Tech in Atlanta and the way the Saints had carved out part of LSU’s market share in New Orleans. He also worried that a pro team would pull away media coverage from college football.

Bryant had intimated such a stance in the past, usually done so in private. When Birmingham got its World Football League team in 1973, Bryant had supposedly placed a call to a bemused Ralph “Shug” Jordan, his head-coaching counterpart at Auburn.

“The story goes that Bryant called Shug and said ‘we need to do something. Like in Atlanta, the pro team is on the front page, and we’ll be on Page 6. We need to stay on Page 1,’” former Birmingham News sportswriter Wayne Martin said with a chuckle. “And (Jordan) said ‘what do you mean ‘we’? You’re the one that’s on Page 1. Auburn never is on Page 1.”

But could college and pro football co-exist in a market like Birmingham? Bryant put forth the example of Atlanta and Georgia Tech, but University of Georgia football was thriving at the time, irrespective of the Falcons.

And even though the Dallas Cowboys were one of the most-followed and highly successful NFL teams of the time, college football still had a toehold in that city due to the annual Texas-Oklahoma game, the Cotton Bowl Classic and SMU’s recent run of winning seasons. Joe Horrigan, former executive director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, told AL.com that while the battle for ticket dollars was a real thing prior to the explosion of television contracts in the 1990s, the rivalry between college and pro football was a tale as old as time.

“Historically, I can go all the way back into the 1920s when the (NFL) was starting, college coaches would blast the pro game,” Horrigan said. “There was this attack or assault on amateurism. And yet the most-vocal speakers on behalf of amateurism are the paid coaches that were just coaching professionally with college teams. They were paid, they weren’t amateurs, but they were the ones that were most opposed to it. It’s always interesting. It makes you kind of chuckle when you look back.”

Auburn coach Ralph “Shug” Jordan, left, is shown with Alabama’s Paul “Bear” Bryant during the 1970 Iron Bowl at Legion Field. Both worried that professional football in Birmingham might draw media attention away from their teams and others in the state. (Birmingham News file photo by Ed Jones)Alabama Media Group

However well-founded Bryant’s worries might or might not have been, they hit Birmingham’s pro football boosters like a gut punch. Chamber of Commerce director Don Newton was so shocked he wouldn’t comment publicly, and others were left “puzzled” by Bryant’s remarks.

“Nobody is willing to go public and challenge Coach Bryant,” one anonymous member of Birmingham’s pro football committee told The Post-Herald. “After all, this is the ‘Year of the Bear.’”

Tom Cosby, who worked alongside Newton for many years, told AL.com that Bryant effectively killed any chances of the NFL coming to Birmingham while he was still alive.

“I don’t have empirical proof, but that was always said, that he would and he did,” Cosby said.

In the early 1980s, Alabama was still playing several games per year at Legion Field, which would have also housed any NFL team that came to the city. That meant Bryant had influence over the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board, which operated and maintained the stadium.

Walter Garrett was manager of Legion Field from 1968-2005, and said he’s always heard rumors about Bryant lobbying behind the scenes against pro football. But Birmingham had a team in the World Football League during Bryant’s early 1970s heyday, and Garrett said he never heard anything directly from the coach about keeping an NFL team out of Birmingham.

“He never expressed that to us,” Garrett said. “He never would be a part of any discussions we had anyway.”

Still, Bryant had enormous influence among Birmingham power brokers and generally got what he wanted.

Paul Finebaum was a young reporter at the Post-Herald in 1981 and covered Bryant’s remarks to the Birmingham Monday Morning Quarterback Club regarding the NFL. He wrote a handful of follow-up stories about the controversy, and came to the same conclusion about the Magic City and professional football as Cosby and others did.

“I talked to a number of people that claim to have known, and the story always was that Bryant killed it,” Finebaum said. “… He had seen what happened in Atlanta and that was not going to happen in Birmingham. He knew how dangerous the NFL was. And by the way, he was right.

“… It was always a dicey story because there were the devotees who couldn’t believe it. Nobody really wanted to blame Bryant. I think that Quarterback Club (speech) in ‘81 is the only time he ever really talked about it. And even though I interviewed him a couple of times for other things, it was just never important enough to dig into because the story was pretty obvious. And even during the 80s, it was a long shot. But it’s just another story of Birmingham missing out.”

Bryant died in January 1983, and by that time Birmingham had secured a franchise, the Stallions, in the original United States Football League. That outfit would play its games in the spring, however, and thus wasn’t a direct competitor to either Alabama football in particular or college football in general.

The Birmingham Stallions of the original United States Football League played at Legion Field from 1983-85. The league folded after trying to move to the fall to compete directly with the NFL. (Birmingham News file photo by Frank Couch)Alabama Media Group

The USFL was formed as a 12-team league in mid-1982 with TV executive Chet Simmons (a University of Alabama graduate) hired as commissioner. The league immediately showed it was serious by securing a two-year, multi-million-dollar broadcast deal with ABC Sports.

Marvin Warner, a Birmingham native who had made his fortune in banking and had at one time been United States ambassador to Switzerland, headed up the ownership group. Birmingham business executive Jerry Sklar came aboard as president and general manager, with veteran NFL coach Rollie Dotsch, recently of the Pittsburgh Steelers, hired as head coach.

It seemed that, finally, Birmingham was approaching the pro football pinnacle.

“I covered the Birmingham Stallions and that was big-time,” Finebaum said. “That’s as close as we’ve ever come to legit NFL football.”

Some in Birmingham still believed that the city’s dalliance with the World Football League a decade before had killed any chances of an NFL team. There was initially the same fear when the USFL formed, though it “ended quick,” Sklar said.

The USFL had a regional draft, and Birmingham focused on bringing in talent with SEC and in-state ties. Former Auburn center Tom Banks joined the Stallions after several years with the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals, as did wide receiver Joey Jones after finishing his Alabama career in 1983.

“One thing I’ll always remember was how well-run the organization was,” Jones told AL.com in 2018. “It was run extremely well. Coach Dotsch was as good a coach as I’ve ever been around – real tough on you, but a great coach. The administration, starting with Jerry Sklar, they were just top-notch.”

The USFL’s biggest personnel splash, of course, came when the New Jersey Generals signed Georgia’s Heisman Trophy winner Herschel Walker. The NFL at the time did not allow underclassmen to enter its draft, and Walker jumped to the USFL rather than return to college for his senior season in 1983.

The Stallions played their first game on March 7, 1983, a Monday night. Despite rainy conditions, more than 38,000 showed up to see the game, which Birmingham lost to the Michigan Panthers 9-7.

Birmingham went 9-9 that first year and drew 20,300 to Legion Field for the season finale against Tampa Bay on July 2, a Saturday. It was during that 1983-84 offseason that the USFL’s mission statement seemed to change.

The USFL expanded from 12 to 18 teams, including putting a team in Memphis, the Showboats. Some of the league’s owners — most notably Donald Trump, who had bought the Generals in 1984 after unsuccessfully attempting to purchase the NFL’s Baltimore Colts — were no longer satisfied with being a “spring alternative” to the more-established league and began making rumblings about moving to the fall.

USFL owners also began spending like crazy, throwing millions at players such as BYU quarterback Steve Young and Nebraska Heisman Trophy winner Mike Rozier.

The Stallions turned the corner on the field in 1984, however, after bringing in running back Joe Cribbs (a former Auburn star who had reached a contract impasse with the NFL’s Buffalo Bills) and veteran Pittsburgh Steelers backup quarterback Cliff Stoudt. Birmingham got off to a 9-1 start before finishing 14-4, eventually losing to the Philadelphia Stars in a league semifinal game.

The Feb. 26, 1984, season-opener against Walker and the Generals drew a league-record 62,500 to Legion Field on a Sunday afternoon. Attendance fluctuated the rest of the year, but the Stallions played before 50,000-plus in Memphis in June and drew 32,000 for a first-round playoff victory over Tampa Bay in July.

“We filled up Legion Field when we played Herschel Walker and the Generals,” Sklar said. “So there was no question that if the National Football League had come in here, they would have been very popular.”

Donald Trump became owner of the USFL’s New Jersey Generals in 1984. Soon after, he began to agitate for the league to move its games to the fall to compete with the NFL. (Circa Images/GHI/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)Universal History Archive/Univer

That 1984 season might have been the high-water mark for pro football in Birmingham, however. Factors outside the team’s control nearly derailed the team’s third year.

Just weeks into the 1985 season, Warner’s Home State Savings Bank was seized by Ohio banking regulators as part of a widespread savings and loan scandal. He was forced to give up controlling interest in the Stallions, with minority owners — and even the city of Birmingham — counted on to pick up the slack.

The USFL had also shrunk from 18 to 14 teams, and many top players in the league began making preparations to defect to the NFL. The USFL formalized plans to jump to the fall in 1986, and owners filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NFL.

Nevertheless, the Stallions continued to win. Buoyed by strong performances from Stoudt and Cribbs and a pro football record 16 interceptions from Chuck Clanton, Birmingham finished the regular season 13-5.

The Stallions beat Houston 22-20 in the first round of the playoffs, earning the right to host the Stars (now based in Baltimore) in a league semifinal at Legion Field on July 7, 1985. Baltimore won 28-14 before a sparse crowd of just 23,350.

Baltimore beat the Oakland Invaders the following week in the championship game, and the league began to fall apart shortly thereafter. By the end of July, Oakland had fired its front-office staff, and teams in San Antonio and Portland had released their entire rosters.

By March of 1986, the USFL had dropped to eight teams, including Birmingham. The antitrust trial against the NFL began in May, ended with a USFL victory, but famously only a $1 award from the jury (which was tripled to $3 under federal anti-trust law).

So, the USFL was effectively dead. All that was left was regret.

“I don’t know how you could go head-to-head with the NFL,” Jones said. “I felt like they should have left it a spring league and it would have been what it was. We were averaging, just from my memory, probably 33,000 a game — good crowds. For what it was, I thought it was an excellent league. But moving to the fall, going head-to-head with the NFL, wasn’t smart.”

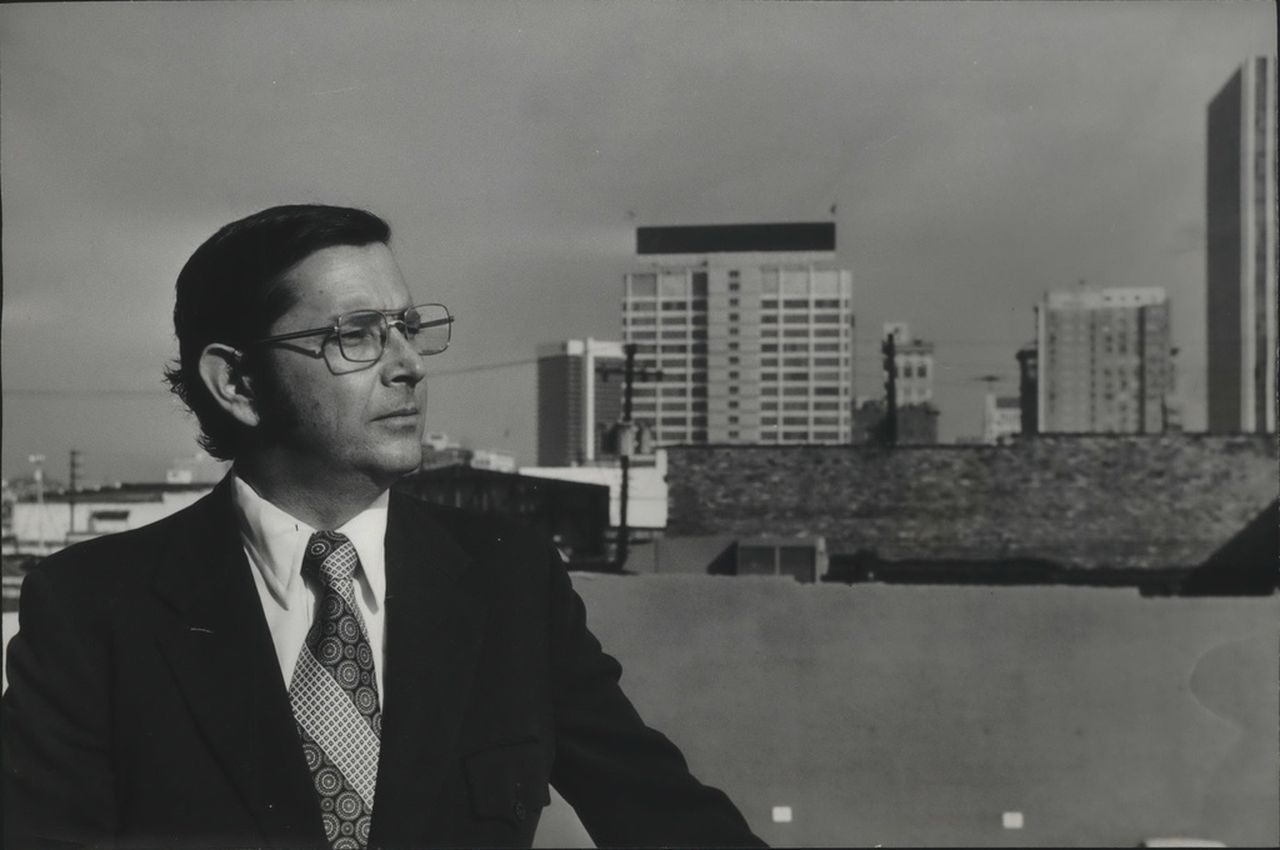

Don Newton, shown here in 1973, headed up Birmingham’s efforts to land an NFL team in the 1980s while he was president of the city’s Chamber of Commerce. (Birmingham News file photo)

It has always been theorized — though he has refused to admit it over the years — that Trump’s ultimate aim in pushing for the USFL to move to the fall was so that the NFL would give in and invite a handful of teams into its league as part of a limited merger. Rozelle flatly denied any such plan existed, though many in Birmingham hoped it might be the case.

“That was the thinking behind every one of these leagues — if we really do well, if we really support it well, if the league does well,” Cosby said. “You have to remember, the mentality was, we saw what happened with the AFL being merged into the NFL. We always thought that would happen with the WFL, USFL, you name it.”

The Orlando Sentinel reported in June 1986 that the NFL was considering paying $20 million to each of the remaining USFL owners and folding six teams into the league to settle the lawsuit, but the story was quickly denied, at least publicly. Sklar said there were definitely some informal conversations between USFL executives and NFL owners.

“I spoke with the owner over in Atlanta, Rankin Smith (of the NFL’s Falcons),” Sklar said. “And when our league went down, he came over and we spent a day and a night talking about every player on our team and what happened. And they were genuinely interested in some of the USFL franchises.”

In addition to the competition for players from the USFL, the NFL was beset by numerous problems in the 1980s. Player strikes in 1982 and 1987 had cost the league money and prestige and left no appetite for expansion.

Three teams moved cities in the 1980s, and two of them were met with opposition from the league. The Oakland Raiders left for Los Angeles in 1982, after the Rams had vacated the Los Angeles Coliseum for suburban Anaheim.

Raiders owner Al Davis tied the NFL up in court, opening the way for the Colts to move from Baltimore to Indianapolis in 1984. Phoenix finally got its NFL team in 1988 when the Cardinals moved from St. Louis.

By 1987, the NFL was making rumblings about another round of expansion. Memphis again took the bait, sending FedEx CEO Fred Smith to meet with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle at the Super Bowl.

Newton and the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce sat this one out, however, having been burned too many times. No potential owner had emerged for a possible Birmingham franchise.

“I really don’t think Memphis has a snowball’s chance of getting a franchise,” Newton told the Birmingham Post-Herald. “I really don’t see much of a likelihood of the NFL choosing Birmingham in the near future. … Right now, I think the (cities) they are looking at are New York, Oakland and Baltimore. That leaves the rest of us to wait until another expansion.”

In fact, the NFL wouldn’t expand again until 1995. Birmingham would not receive serious consideration in that round, either, leading local football boosters to seek alternative measures.

NEXT UP: The final part in the series covers one last effort to land an NFL team in Birmingham, and examines the city’s present and future potential in professional sports.

Creg Stephenson has worked for AL.com since 2010 and has written about football for a variety of publications since 1994. Contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter at @CregStephenson.