Battered woman shot her abuser 32 years ago. Alabama’s parole board won’t let her out.

Her face still bears a scar from the abuse Marguerite Brooks suffered in her short marriage.

“I don’t know why I married this man,” she told AL.com from a prison phone. “He was the worst person I’ve ever been with in my life.”

She and Lewis Brooks had been married for about six months when Marguerite, standing just over 5 feet tall and slightly over 100 pounds, fatally shot Lewis in a Montgomery street.

Marguerite didn’t deny the killing. The abuse he inflicted on her, which was detailed in court records, didn’t stop her from being sentenced to life in Alabama prisons. At her trial, the state’s psychologist testified that she suffered from Battered Woman Syndrome.

“It was terrible,” said her son Kenneth Hardy. “He beat her every time he got.”

The shooting happened in the summer of 1992. She was just 27 then.

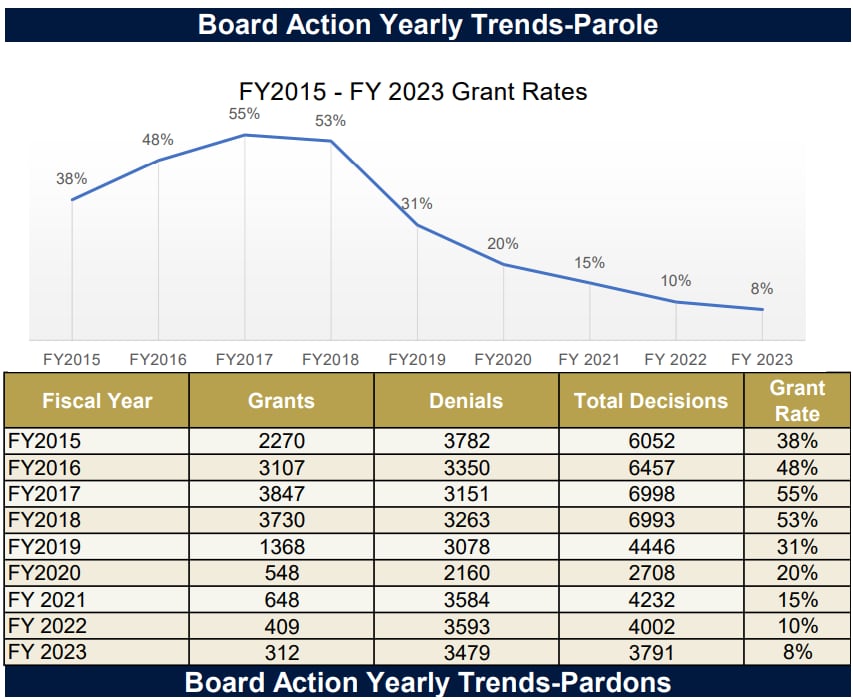

Now, she’s dependent on the Alabama parole board for a second chance, and it’s a long shot. In Alabama, paroles slowed to a trickle last year, as fewer than 1 in 10 eligible inmates got out. The three-member board routinely denied parole to people who have already served decades for drug charges and nonviolent crimes, to people who are in minimum custody facilities and many who are safely serving fast food and working jobs by day, only to return to prison at night.

When it comes to violent crimes, like Marguerite’s, the odds are much lower. The state automatically speaks in opposition to their release, as often does a victims’ rights group. The inmates are not there to speak for themselves, not able to explain a complicated case involving an abused wife.

Despite not having any disciplinaries in prison for the past seven years, Marguerite was denied parole in 2021. She didn’t have a lawyer to speak on her behalf.

Hardy, her son, said he stopped going to the parole hearings. “The last time we went there, the people standing behind the booth, they really didn’t give us a chance to say nothing,” he said.

“You got to just put yourself in her shoes. If a man was beating you over and over, what would you do?”

‘I had to save my own life’

Marguerite will turn 60 this summer. She still bears a scar from the night Lewis Brooks hit her across the face with a glass ashtray, her son told AL.com.

“I will not tell you that I am not sorry for the life being taken, because I am,” wrote Marguerite in a letter to the judge who sentenced her. “But I had to save my own life.”

Gabrelle Simmons and Darryl Littleton, Associate Members of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, and Leigh Gwathney, Chair, listen to supporters of offenders during a hearing at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama, January 9, 2024. Tamika Moore | AL.com

The abuse started quickly in the relationship, according to Marguerite and court records. But problems escalated when Lewis robbed the convenience store where Marguerite worked.

Lewis came in while she was on shift, holding her at knifepoint during the robbery.

She didn’t push the emergency button or call 911 at the time, she said, because Lewis said he would “completely cut your throat before the police get here.”

After Lewis was caught, he told police that Marguerite was involved. She was charged, but the case was later dropped.

Marguerite was upset about being charged, she would later tell police, and told Lewis she wouldn’t be able to find another job and was at risk of losing her children. She already had two young boys when they married.

And on the afternoon of Sept. 18, 1992, Marguerite’s sons — just 5 and 9 at the time — told their mom that Lewis was looking for her, court records said.

Marguerite and a friend were walking in their Montgomery neighborhood when Lewis and his friend drove up. There was an argument, according to appellate court records, and Lewis grabbed Marguerite’s shirt and jerked her toward him. She got free, and the women headed back to Marguerite’s mother’s house. As the men followed, the argument continued.

“Just let her come home… she did her time.”

Kenneth Hardy

The man who was with Lewis told the court at trial that Lewis had said he was “going to kill that bitch.”

Records from the appeals court say Lewis was “drunk and angry.”

As the fighting escalated, Marguerite told police, Lewis and his friend kept trying to get her to come down the street. When Marguerite and her friend got to Marguerite’s mother’s house, she went inside and got a gun. She went back outside.

She told police: “He said, ‘Bring your ass here,’ he said, ‘I ain’t gonna say it no more.’”

She told him she was tired of him hurting her.

“I said, ‘I’m tired of you jumping on me and harassing me,’” Marguerite told the cops, detailed in a transcript of her initial police interview. According to the appeals court, Lewis advanced toward her despite her warnings that she would shoot.

“You got the gun, go on and do what you got to do,” he told her, according to court records.

This spring, Marguerite told AL.com that she understood his words to be a threat and that he reached inside his pocket.

Marguerite fired.

She knew she would spend time behind bars. But Marguerite said she never thought it would be the rest of her life.

A chance at freedom

Marguerite has come up for parole before, always getting denied.

At first when her case came before the parole board in the early 2000s, Marguerite said the board denied her due to disciplinary citations in prison.

Over 31 years, she’s faced dozens of disciplinaries. Most of them were in the 90s, when she had first been sent to Julia Tutwiler Women’s Prison. She hasn’t received one since 2017, and that one was for smoking in the wrong place.

Marguerite said she doesn’t know why the parole board doesn’t deem 31 years enough for killing the man who, she thinks, would have killed her.

Paroles have declined sharply since 2015, as shown by the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles data. Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles

Court records show in 2009, a welding instructor from J.F. Ingram State Technical College wrote a letter calling Marguerite an “exceptional student” and describing the school’s pride in her. He recommended her for any opportunities she could get.

Records from Marguerite’s last parole hearing show that a representative from a victim’s rights group spoke against her release, along with someone from the Alabama Attorney General’s Office. One of Lewis’s daughters — from a relationship he was having at the same time he was married to Marguerite, she said — contested her parole, too.

She is not set for another parole hearing until August 2026. Currently, she’s housed in what the Alabama prison system calls “minimum-out” custody. The department describes the custody level as “appropriate for inmates that do not pose a significant risk to self or others” and can work off site without direct supervision.

Would she have shot Lewis today, knowing what she knows now?

“To save my life?” she asked AL.com. “Yes.”

The state’s expert psychologist, Dr. Karl Kirkland, testified during Marguerite’s trial that her “status as an abused woman or wife played a major role in her behavior at the time of the offense.”

“Just let her come home,” said Hardy, her son, recalling life with Lewis and recalling his mom protecting her sons from from the violence.

“She did her time.”

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.