As Native Americans contend with more extreme weather, some die waiting for help

A few days before Christmas, Oglala-Lakota tribal member Alice Phelps was driving through one of the worst winter storms to hit the enormous Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in decades.

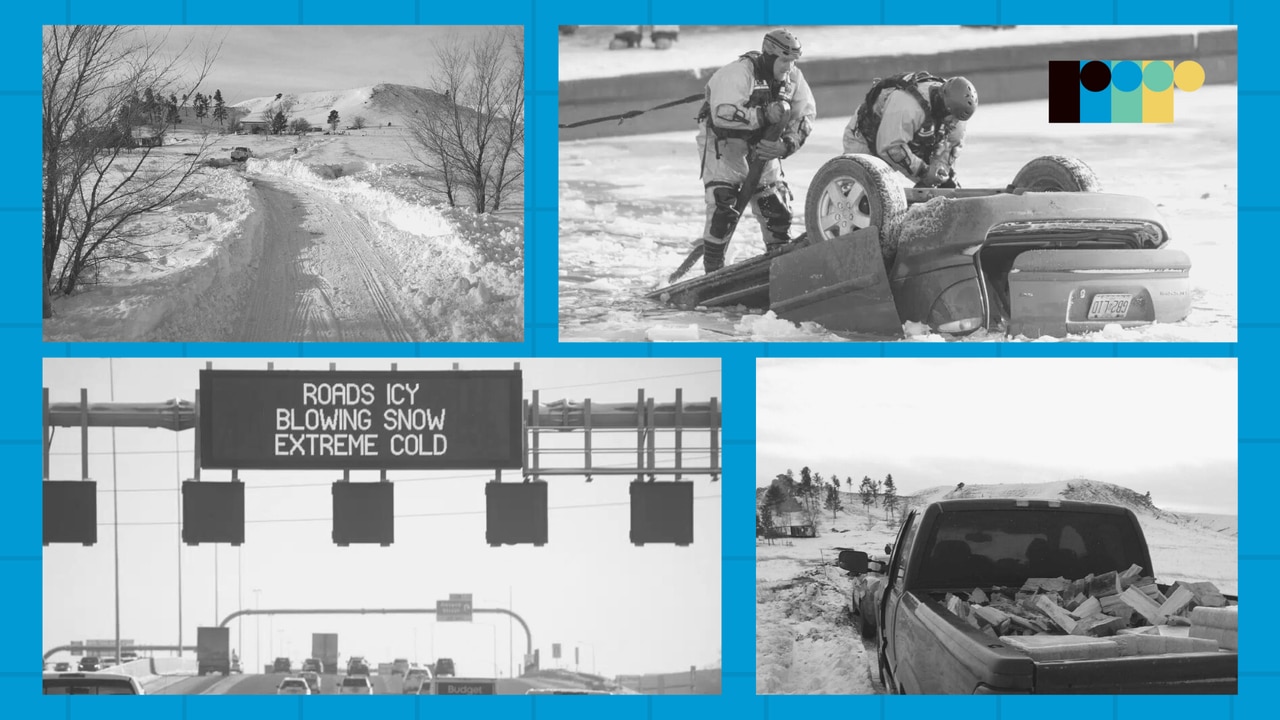

Temperatures in the reservation – the location of the infamous Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where U.S. government forces killed 300 Lakota people – plummeted to around minus 35 in some areas and visibility was zero as a ferocious ground blizzard swept across the vast plains of the Midwest.

It was a complete whiteout, according to Phelps, who said it was one of the scariest experiences she’d had during South Dakota’s harsh winters.

“I had my two sons and we were freaking out because we couldn’t see anything and if you stopped, you were going to get hit,” she told Reckon.

The best roads on the reservation, which is the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined, were barely passable and snow drifts in some places were as high as 12 feet, said Phelps, Principal of the American Horse School in Allen, a small settlement within Pine Ridge.

While driving through the storm, she suddenly caught a glimpse of an 18-wheeler lorry through the blizzard. She swerved to avoid a collision and her car landed in a nearby ditch. Another car was clipped from behind by the truck and also veered off the road. The injured driver, a doctor, was rescued, but the car remained in the ditch for weeks.

Thousands of residents across the reservation were subjected to nearly a week without power and water. Propane and wood were in short supply, forcing some to burn clothes to survive. Those living in remote areas became stranded and helicopters were contracted to drop medical supplies. Six deaths were confirmed in the neighboring Rosebud Reservation, including at least one child. Emergency crews took two and a half days to reach a heart attack victim, while cancer and dialysis patients also waited days for volunteers to clear the roads.

In all, people were snowed in for two weeks, according to Phelps. Some roads are still currently impassable.

From Florida to Alaska, Native Americans, already ravaged by generations of anguish and displacement, are now facing the deadly and life-altering consequences of climate change. While the effects of a warming planet have forced many communities to reimagine their relationship with the environment, many indigenous communities do not have the resources or financial power to adapt or survive severe weather.

“It was one of the worst storms to hit us in a long time,” said Phelps, a community leader among the Oglala Lakota Tribe and runs First Families Now, a non-profit charity that helps children and families in impoverished and isolated parts of the Pine Ridge Reservation. “We can handle winter weather, but we don’t have the resources to deal with these serious winter storms and other big changes to our climate.”

Stranded in some of the nation’s most uninhabitable lands, America’s first people are being left behind.

Tribal lands facing challenges

Pine Ridge was later established as a prisoner-of-war camp in 1899 before becoming home to the roughly 20,000 people who live there today. Although, some estimates put the population closer to 45,000.

Today, there are few job opportunities on the reservation due to its remote location. It ranks as the poorest county in the nation. Economic development, infrastructure and reliable communications are almost non-existent, according to a 2019 report to Congress.

“These circumstances also contribute to the many social challenges that our people currently face, which include extreme poverty, alcohol and substance abuse, inadequate health care, and high crime rates,” noted Julian Bear Runner, former president of the tribe, in a report to Congress.

The report noted that unemployment is between 80% and 90%. Half of all people who live in Oglala Lakota County live in poverty. The per capita income is below $9,000 a year and life expectancy is around 67 years old, although other statistics place it at 47 for men and 55 for men.

Climate change activist Greta Thunberg visited the reservation in Oct. 2019. She met with tribal leaders and her Native American counterpart, Tokatawin Iron Eyes, also a teen climate change activist.

A series of disasters have hindered life on the reservation in recent years. In 2011, the reservation was hit by severe drought and wildfires, followed by high winds, tornadoes and catastrophic flooding in 2012. A series of tornadoes hit again in 2016, followed by an ice storm in 2018 and a bomb cyclone in 2019, which left some residents stranded for up to two weeks without food or water.

The USDA declared the area a primary natural disaster after a drought hit the area in June 2021.

But examples of tribes experiencing severe weather exist all across the country.

The Navajo Nation in the American West has experienced severe drought for decades, affecting crops, livestock and drinking water. In Louisiana, the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe is facing coastal erosion, placing at risk their homes and ancient burial mounds. Losing land also allows increasingly frequent and dangerous hurricanes to get closer to tribal dwellings.

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, located adjacent to the Everglades National Park, is concerned that encroaching saltwater and mangrove forests will destroy freshwater marshes and untouched habitats that the tribe used for traditional and cultural practices. That could destroy native wildlife species, resulting in the loss of traditional hunting grounds while sacred tribal areas become flooded.

The Yup’ik people of Alaska hope to relocate because of rising sea levels. Wildfires in Washington state destroyed buildings and killed livestock on the Colville Tribe’s reservation.

Where is the help?

Getting help to deal with these disasters hasn’t always been straightforward.

Until 2013, Tribes were not permitted to ask FEMA for direct assistance. They had to go through the states first. But after the passing of the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act, named after the storm that devastated the east coast in October 2012, tribes can now approach the federal agency directly.

President Trump granted Pine Ridge disaster relief in June 2019 after it experienced snow storms and subsequent flooding in March 2019. South Dakota’s National Guard helped clear some roads after the most recent heavy snowfall.

However, FEMA is less likely to help tribes with disaster relief than communities in the rest of the country, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

On average, American citizens receive $26 per person in federal disaster relief from the Department of Homeland Security, which controls FEMA.

Native citizens receive just $3.

Part of the problem is that FEMA requires each tribe to have a disaster mitigation plan to prove resilience and reduce risk. While all states and over 85% of the country are covered by such a plan, less than half of all tribes have a mitigation plan, according to FEMA. That means tribes may not receive full disaster relief from the government when disaster strikes.

When FEMA stepped up, it was not always helpful.

“I live in a FEMA trailer and they are not meant for South Dakota weather,” said Darlis Morrison Rex Crow, a tribal police officer in Pine Ridge who is often seen around the reservation helping families in need. “If you cover up the vent, it breaks the heating system. So we end up spending more on heating.”

Rex Crow said that most homes on the reservation were overcrowded and that the problem worsens after every winter. When another becomes uninhabitable, they move in with a nearby family member. Homes built for two to four people have as many as twelve people, she said.

Around 40% of tribal homes throughout the country are considered inadequate, while thousands live in FEMA trailers, many of them from Hurricane Katrina.

In August, FEMA announced its first national tribal strategy, which is aimed at building a better relationship with tribal nations.

However, only federally recognized tribes are eligible for assistance, meaning groups like the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe would not get federal disaster relief. There are 574 federally recognized tribes and 400 that are not recognized.

Despite the changes, some believe FEMA and other disaster assistance aren’t doing much to help tribes in need.

“If you travel the country like I have, you see the state and federal government helping when a disaster hits,” said Adam Grieco, who is not Native American and first visited Pine Ridge when he cycled from Virginia to California in 2010. “Outside of the reservation, people can call for help and it will be there pretty quickly. You will probably wait days, if not weeks, on reservation.”

Grieco is a volunteer member of a crew of reservation workers that meets at the Community Assistance Program office each morning. The crew is given various daily tasks, like delivering food and propane tanks, chopping down trees and pulling people out of ditches. He recently extended his stay after his truck broke down.

While tribes have treaties with the U.S. Government that entitle them to certain economic benefits, like housing and education, the level of assistance is often overstated. In reality, U.S. government obligations to Native Americans, which stem from more than 400 treaties, are often underfunded and poorly managed.

And it’s the same at the state level, according to Phelps, who said that Pine Ridge is effectively cut off from South Dakota’s economy and almost entirely void of development.

“It’s like a third-world country here,” said Phelps, who, during the storm, delivered 100 propane tanks to the most in-need families and is currently taking donations to buy heaters and blankets. “We’re completely on our own and the government will only help so much during winter storms and floods. It can feel impossible to exist here for so many people.”

“We never asked to live here, they forced us to be here through the barrel of a gun and false promises,” said Phelps. “Now we’re dealing with devastating weather patterns we had no part in creating.”

But indigenous groups are fighting back.

Throughout the country, various tribes are finding novel ways to endure severe weather and promote sustainability.

In Pine Ridge, underground greenhouses are helping grow food in places that would ordinarily be impossible because of the extreme weather. The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in the Pacific Northwest, one of the first tribes in the country to create a climate change action plan, are using ancient practices to build clam gardens on their coastline. It’s one of the tribe’s many efforts at combating climate change in the region.

The tribe is fighting to block mining operations in British Columbia to protect their waters downstream. To increase shade and reduce river temperatures for the local salmon run, they have planted trees.

In late 2022, tribes across the country launched a collaboration to address broader climate change issues. They will look at new technologies to help remove carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

But at the heart of all these environmental efforts is education, which Phelps says is the key to changing the lives of indigenous communities.

“I see the glass half full,” said Phelps, who, on the anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre on Dec. 29, spent the day inside her family sweat lodge praying for her people of the past, present and future. “If we are going to heal, it’s going to be through educating our young people and making sure they have a bigger voice.”