As migrants arrive from Texas, Chicago advocates strain to meet growing need

Dr. Stephanie Liou had never seen a patient with chickenpox at the Alivio Medical Center on Chicago’s southwest side, where she works as the head of pediatrics and site director. Because of mandatory vaccines, the contagious disease is rare in the U.S., with fewer than 150,000 cases each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But in the last few months, she has seen a “ton” of new cases in migrant shelters across the city.

In the last couple of years, the clinic, which is located about two blocks away from the largest temporary migrant shelter in Halstead, has seen an influx of patients — many who are in need of urgent care but do not have insurance or money to pay for treatment.

“I didn’t go into medicine to count how many patients I see or figure out how to keep the doors open,” Liou, who was raised by a low-income immigrant single mother, said. “But the reality is we were already operating on such limited funds, and now we are seeing so many patients who need more time and more resources.”

The clinic — which serves low-income and uninsured people — and other nonprofit and advocacy groups in Chicago have been operating on overdrive since summer 2022, when Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began bussing and flying out migrants arriving from the southern border.

Liou said she sees between 20 and 25 patients a day.

As of Jan. 5, about 29,657 migrants have sought refuge in Chicago after being bussed from Texas as part of Abbott’s “Operation Lone Star,” according to the city’s new arrivals dashboard. Nearly 636 buses have arrived since August 31, 2022. Since June last year, at least 4,000 migrants were flown in by airplane.

“Many new arrivals survive brutal and dangerous journeys to border states and are promptly and inhumanely transported with little to no triage,” Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson said in a statement. “As a result, interior cities like Chicago are receiving new arrivals with more severe medical needs.”

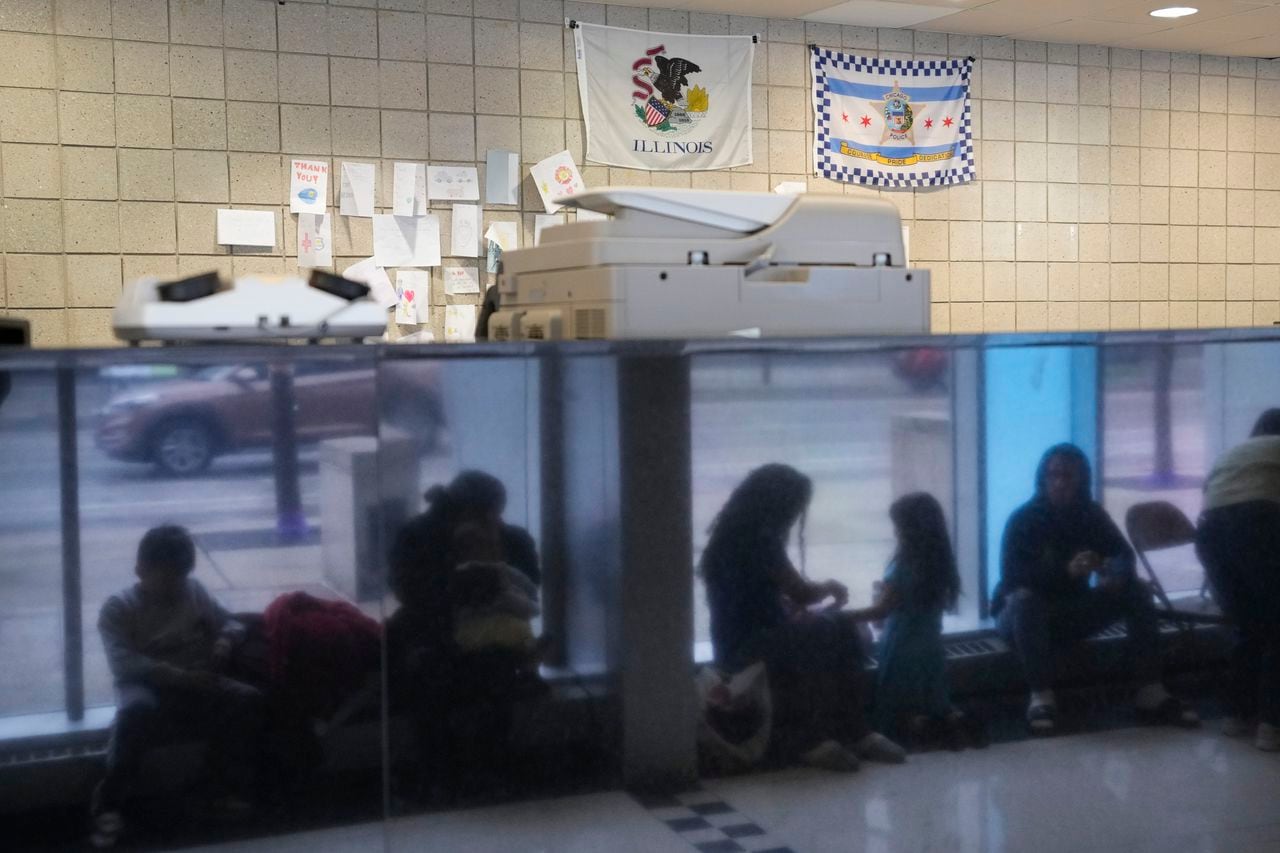

More than 14,000 migrants fill about 27 temporary shelters in Chicago, with more than 300 refugees awaiting placement. City officials said more than 1,000 asylum seekers and migrants were sleeping on the floors of police stations, airports and outdoors awaiting shelter from the winter weather.

Although the city established criteria for safe and secure shelters, many of these places are overcrowded, do not adequately protect from the cold and are prone to disease outbreaks, immigrant advocates said.

“I talk to parents every day who have gone through challenging, long, dangerous journeys to get here and they do it because they want a better future for their family and for their children,” Liou said. “Even if they’re living in a shelter with 2,000 other people and there’s six disease outbreaks going on in their midst — they feel like there’s a chance here.”

The Halstead shelter recently came under heavy scrutiny after a 5-year-old boy became sick and died on Dec. 19. His family had arrived in Chicago on Nov. 30.

City officials, citing the incident report, said shelter staff saw the child experiencing a medical emergency and began performing chest compressions until first responders arrived. The boy was taken to a local children’s hospital where he was pronounced dead.

Officials said the cause of death is under investigation and claimed that the incident is not related to a disease outbreak in November that sent three children to the hospital. The Chicago Department of Public Health said the boy did not appear to die from an infectious disease and there was no evidence of an outbreak at the shelter.

Other refugees in the shelter were transported by ambulances to local hospitals and many others were discharged with symptoms of respiratory virus, but officials said the cases are not related except for the location where they happened.

City-run shelters operate 24 hours a day, with an 11 p.m. curfew for guests. Case managers onsite connect migrants with health resources and other support, according to officials. A 60-day limit was recently imposed at the shelters to “accelerate how new arrivals engaged with the emergency shelter system,” according to the city website. Officials said the goal is to resettle people in Chicago or Illinois, or to help them reunify with family or sponsors elsewhere.

Officials said the city receives limited information about the number of arrivals by buses and airplane, but noticed an “unprecedented increase and frequency of buses” followed after Chicago announced it would host the Democratic National Convention in August.

Karina Ayala-Bermejo, the president and CEO of Instituto del Progreso Latino (Institute for Latino Progress), said Chicago must take that opportunity to show the nation how it handles a crisis. The institute is a nonprofit that helps immigrants by providing education, training and employment opportunities and legal services.

Ayala-Bermejo said they receive some funding from Chicago and the state, but much of what “propels the project forward is generosity from individuals,” with about 400 people volunteering to aid migrants.

“But we shouldn’t be at this point,” Ayala-Bermejo said. “We should be supported by the federal government in a larger way to address what is clearly a man-made humanitarian crisis.”

The institute worked with Chicago to set up an Amazon gift registry for donations of essential items to refugees in shelters. More than half a million items have been donated, she said.

“We could triple what we have and still not meet the need,” she said. “But we’re doing the best that we can.”

Through the institute’s Project AMOR (Asylum Migrant Outreach Response), staff and volunteers meet with migrants sheltering at police stations and airports, providing them with necessary items and information.

“They are embedded in the shelters, and the level of commitment and passion that you need to continue at that rate and not to take on vicarious trauma is so immense,” she said. “Unfortunately, we do find that we always have vacancies to be filled.”

Alivio Medical Center, which now has seven locations across Chicago’s southwest side, was founded in 1989 by Mexican immigrants and activists in the Pilsen neighborhood to care for marginalized members of the community. Since summer 2022, the number of patients has largely increased at the medical center.

“I don’t think anyone here in Chicago who’s doing this work has the resources that they need or the time or the emotional support,” Liou said.

She said the center has adjusted its operations due to the influx of migrant patients. Newly-arrived people now have 30 minutes to provide their full medical history and concerns. If they reduced appointment times, they would see more people but have even less information about each person, Liou said.

Ayala-Bermejo has spoken with families sleeping at police station floors and she’s welcomed people arriving by bus. She remembers children excitedly pointing out the Chicago skyscrapers, tall buildings like they had never seen before. And some adults she spoke with were frustrated with the long and complicated process.

“I can’t blame people for wanting something more because that’s what brought my family here,” Liou said. “That’s why I’m here.”