Archibald: Mary Allen Jolley almost died, and then she was unstoppable

It has been said that Mary Allen Jolley lived a Forrest Gump life.

She came from humble Alabama beginnings and modest ambitions and rose, sometimes compelled by forces beyond her control, to exalted places.

She came to rub shoulders with presidents, to take part in world-changing events. Her work helped millions get an education, pulled women into math and science long before STEM was even a seed, and assisted in the birth of Alabama’s automaking industry.

But Mary Jolley was no Forrest Gump, bumbling as he did through his fictional story. Jolley seized her very real life, even when it threw her curveballs, and used skill and persistence and audacity to change the world.

For those who knew her.

For those who never heard her name.

Jolley died in December. She was 95. Her funeral will be Friday in Tuscaloosa. But please do not think this an obituary. It is, like Jolley’s life, something more.

Because this story could have been a tragedy about a life cut short long ago, a career upended by illness and stained by disappointment. It is instead a parable of indomitable spirit, of what can happen when strong people refuse to accept wrongs as simply the way things are.

When people talk about Mary Jolley they inevitably talk of that spirit.

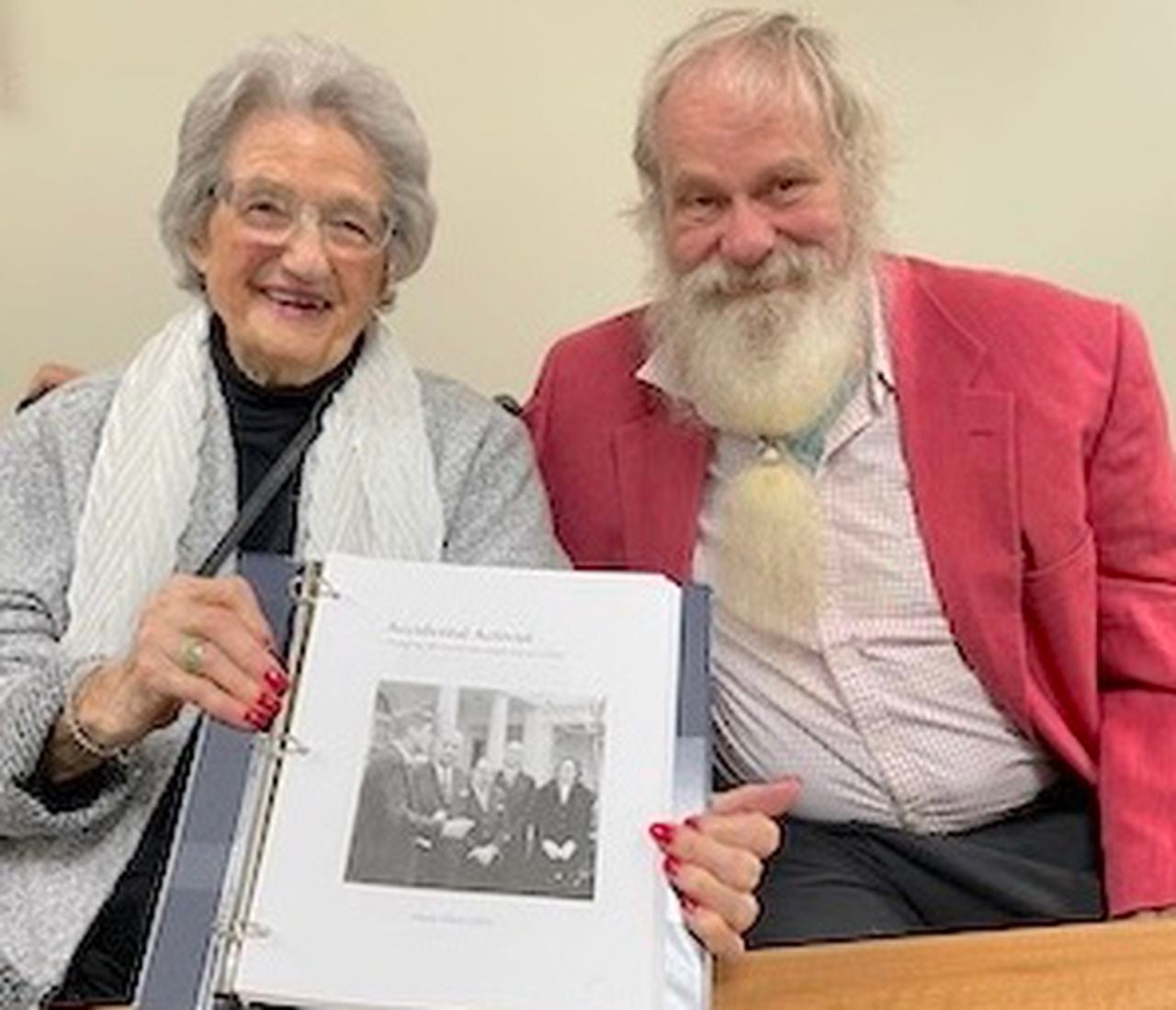

Mary Allen Jolley with Julian Butler following the Profile in Courage Award Ceremony at the University of Alabama.

Dan Liss, a Rhodes scholar-turned tech CEO who came to know Jolley during a campaign to increase enrollment in Obamacare, recalls a conversation from a few years back, when Jolley turned 93.

“She said to me, ‘Dan, my ankle’s so bad I can no longer walk backwards. I can only walk forward.’”

Liss thought it a metaphor for our time. It’s a summation of her life.

Ever forward. Ever moving. Ever hopeful.

Stories about her determination would fill a book – not just her own, “Accidental Activist,” which she proudly finished before she died and is slated for publication in June.

Family members tell how they came to expect marching orders with every visit. She didn’t tell them to go make the world a better place. She gave them specific steps for how to do it, often with phone numbers attached.

Jan Pruitt, who refers to herself as Jolley’s editorial assistant, talks about the end of Jolley’s life. She fell into a days-long state of unconsciousness, and friends thought she might be gone. But suddenly Jolley woke, asked for a taco salad, ate it, and fell back to sleep.

She died not long after. She knew what she wanted. Until the end.

‘What do you mean a woman can’t drive?’

Liss points farther back, to the beginning. It was 1943 and Jolley – Mary Allen, then – was a freshman at Ward School in rural Sumter County.

Her brother, the school bus driver, left to fight in World War II, leaving Jolley and about 20 classmates without a 15-mile ride to school. Over protest she marched to the county seat, took and passed the driver’s test and became that county’s first female bus driver.

“That captures her spirit,” Liss said. “What do you mean a woman can’t drive? What do you mean I can’t be the bus driver? Why not? Will they give me a license? Okay. I’ll go get my license. You almost can’t teach that kind of spirit.”

To me, though, the story that says it all – not just about her, but about her legacy – is the one that almost killed her.

Jolley graduated from the University of Alabama with an education degree and was hired to teach music and girls PE in Frisco City, in Marion County. In 1951 her life was taking shape.

Until the doctor gave her terrible news. She had tuberculosis. She was sent to a sanatorium.

“She got worse and worse,” said her nephew William Loyd Allen. “She assumed she would not survive.”

But the use of streptomycin as a TB treatment had just begun, and she received massive doses. It cured her. But TB changed everything.

She was set to return to Frisco City, where she roomed in a teacherage with her colleagues. But they refused to let her back in. They were afraid of the disease. She had become a pariah.

“That was when she understood prejudice for the first time,” Liss said. “She wasn’t allowed back to teach because the teachers wouldn’t let her, because of misinformation. She had to reinvent herself.”

And boy, did she.

That moment, that near-death, hard-life experience, changed everything, like the flap of a Black Belt butterfly’s wings.

She would take a job with eight-term Congressman Carl Elliott of Walker County, who gave her more responsibility as his trust in her grew.

And gradually the woman who had been thrilled to be a school marm in rural Alabama found herself side by side with senators and congressmen, working on a plan to give more struggling people a pathway to college education.

She and Elliot put hard work into that idea, but it was the Soviet launch of Sputnik that propelled the National Defense Education Act of 1958 to reality. That act created the low-interest loans that have been used by tens of millions of Americans to pay for college, graduate school and vocational programs.

It is impossible here to speak of everything she had her hands in, of all the noes she refused to take for an answer.

Mary Allen at age seven in Sumter County.

When Adm. Hyman Rickover, the so-called father of the atomic sub, shouted on the phone that he was too busy to testify before a congressional committee about a bill he didn’t know anything about, she went to his house on a Saturday and told him why he should care. He wound up, as she writes in her book, testifying after all.

There is so much more. Appointments by presidents Kennedy and Johnson gave her a key role in building legislation that funded education and workforce development. Her work in higher ed in South Carolina brought women into math and science careers long before that was cool.

She even gets credit for helping launch Alabama’s automotive industry. As former UA Chancellor Malcolm Portera has been quoted as saying, Jolley “came up with a strategy to recruit automobile manufacturers to Alabama.”

Pounding the table

It is easy to be struck by the magnitude of it all. She did big things. But along the way she saw the importance of the things others might think of as small.

Jolley, in that soon-to-be published book, describes watching miners disabled by black lung disease arrive at Elliott’s office.

“There was no elevator in the Jasper Federal Building,” she wrote, “so those men had to climb stairs, arriving in the office so out of breath and racked with coughing that I sometimes thought their lives might end right in front of my eyes.”

She campaigned for JFK in 1960, and when he took office she told the president the problem, and asked for help. In three months the building got an elevator.

It wasn’t all she wanted – she wanted better working conditions for miners and legislation to address the causes and costs of the disease, which would come later.

But it is testament to how she saw the plight of people being harmed by larger problems, and found ways to help. She expected that of herself, and she came to expect it of others.

Liss, along with Josh Carpenter – another Rhodes scholar and now president and CEO of Southern Research, met Jolley when the two set out to train students to talk to people about enrolling in Obamacare at a time when Alabama politicians spent money on political ads blowing it to bits.

They were told they had to meet her, so they went to Tuscaloosa.

They were in their 20s, eager. They walked past decades of newspaper headlines, honorary degrees, and pictures of Jolley with presidents to find an 85-year-old woman in her assisted living apartment. They looked at each other, unsure what to expect, and then launched in on their bold plan:

They intended to reach 100 students in Tuscaloosa alone, they told her, proud, and 1,000 across the state.

“OK,” Jolley replied matter of factly. “A thousand in Tuscaloosa.”

The young men were unsure if Jolley heard properly, and Carpenter quickly corrected her.

“Dr. Jolley, we said a hundred in Tuscaloosa.”

Jolley pounded on the table.

“I said 1,000 in Tuscaloosa!” she reiterated. And there would be no argument.

The two, and their group, Bama Covered, went to work, and Jolley became the most important advisor to a campaign, Carpenter said. The group had more than 100,000 personal conversations about enrollment across Alabama, and the state’s enrollment surpassed predictions. The group, and the numbers, were even lauded in the New York Times.

Jolley with Dan Liss and Josh Carpenter at her 90th birthday celebration in Tuscaloosa.

The parable of Mary Allen Jolley

Jolley always saw a way.

“She had this unbelievable sense of humor, and then she would say these audacious things in this gentle drawl,” Carpenter said. “She had a sense of possibility that was inspiring and contagious.”

Former Alabama First Lady Marsha Folsom was in tears, a week after Jolley died, because she would miss her mentor and friend, because the world needs a Mary Jolley.

Because Jolley didn’t just believe in hope, she believed in finding ways to give us all reason to hope, to believe in each other.

I just can’t stop thinking of that butterfly flapping its wings, of how a rural Alabama teacher faced tragedy, and turned her own misfortune into a gift to the world.

She didn’t look at troubles – including almost dying and being ostracized by her peers – as setbacks, Folsom said.

“She looked at those as learning experiences, and she gained wisdom from them,” Folsom said. “That’s something I think we should all learn from.”

That is the parable of Mary Allen Jolley.

In our finest moments we might just be able to change the world. It is in our weakest moments, though, when we find the strength to change ourselves.

John Archibald is a two-time Pulitzer winner at AL.com.

Mary Allen Jolley in November delivers her “Accidental Activist” manuscript to Joe Taylor, director of Livingston Press at the University of West Alabama.Special