Archibald: Even the dead can’t get paroled from Alabama prisons. It’s time to look ‘em in the eye.

This is an opinion column.

How do you know when someone’s lying to you?

You start by looking ‘em in the eye.

How do you show you’re taking someone seriously?

You look them in the eye. It’s the least you can do.

How do you refuse to grant parole to a man who died in prison 10 days earlier?

You don’t even bother to look at them at all.

On February 27, a 55-year-old Lineville man named Fredrick Bishop was found in dire shape at Easterling Correctional Facility in Barbour County. He was, prison officials said in a statement, taken to a health care unit, where attempts to save him failed. The cause of his death has not been determined or revealed.

On March 9, a week and a half later, Fredrick Bishop’s name came before the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles. He was eligible for release on a 2008 robbery. The two members of the parole board present that day – they are now back up to a full panel of three – denied his parole.

They didn’t even bother to know he was dead. Why would they?

It’s not like in the movies, where inmates like Morgan Freeman’s Red plead their cases before a panel. No one gets that privilege in Alabama. Those up for parole are never allowed to attend hearings, so Bishop, dead or alive, was denied on the spot, like 20 of the 21 other people the board ruled on that day.

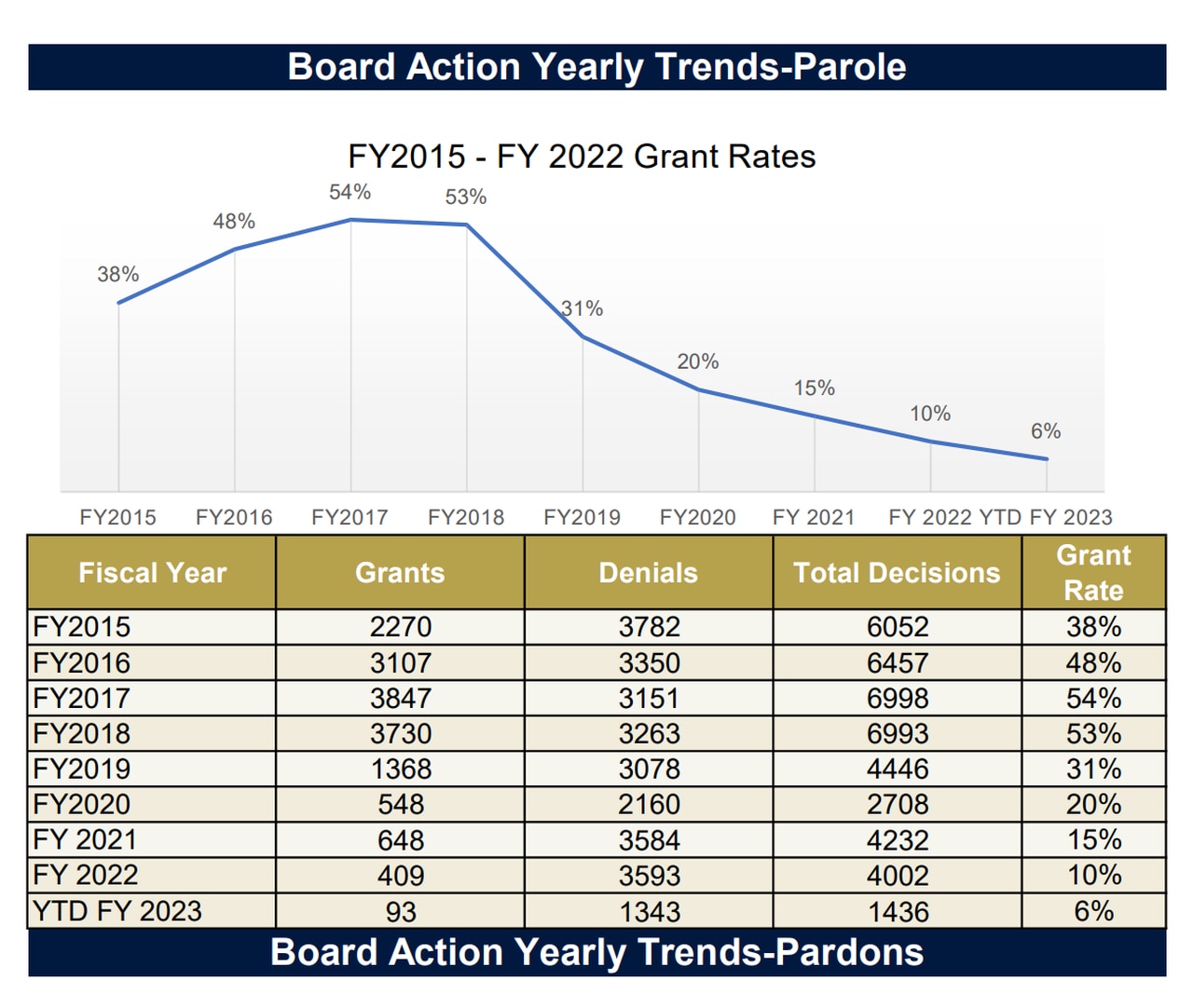

Data from the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles shows the declining rates of those granted parole in the state. (ABPP)

So far this year that panel has decided the fates of 792 people. It has granted parole to 25 of them. That’s 3% of eligible people.

They didn’t have the brass to look any of them in the eye.

They don’t have the decency to look at them as human.

“I can’t believe they did that,” Bishop’s mother, 79-year-old Dorothy Jean Bishop, told me. But she stopped short, and changed her mind.

“I believe it. Because they don’t care.”

Ms. Bishop, of Lineville, knows it’s too late for her son, but she wishes parole board members could have at least seen him face to face. Then, perhaps, they could have seen in him a glimpse of the things she saw.

She wishes they could see the good boy who ran up the hill to shoot hoops, or the young man with many friends who played guard for Lineville High School’s basketball team. She wishes they could have seen the man who joined the Army and spent years there. She wishes the prison system had seen the man coughing in bed for weeks. She wishes any of them had simply taken the time to see her son as a person, and not just a number.

“You can’t bring him back, but God knows,” she said. “I don’t think they really took care of him.”

They did not. Alabama’s prisons remain under federal scrutiny for dangerous conditions. At least 266 people died in prison last year, and the percentage of those paroled fell from 50 percent of eligible inmates in 2017 to just 9 percent last year.

There are ways to improve the process. The parole board could and should have more members, more hearings, including some at prisons, where it could see inmates face to face. It should make it a point to look people in the eye. It should make a point to be human, to see humans instead of just case files.

In the end, Bishop said, the situation doesn’t show her son’s inhumanity. It reveals theirs.

“The people that are doing it are not human,” she said. “They don’t care about regular people.”

The parole board did send out an apology after realizing it had denied parole to a dead man.

“The Bureau apologizes for any confusion this may have caused interested parties and will continue to take steps to avoid this and similar situations in the future,” it said.

In it, it misspelled Fredrick Bishop’s name.

John Archibald is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for AL.com.