Archibald: Alabama torturing these inmates should shock us

This is an opinion column.

One inmate was baked. As if in an oven.

Tommy Lee Rutledge’s body temperature was 109 degrees when he was found, on Pearl Harbor Day in 2020, in a scorching mental health unit at the federal Donaldson Correctional Facility outside Birmingham. He was 44.

Another inmate was frozen to death. Apparently stored like meat in a freezer.

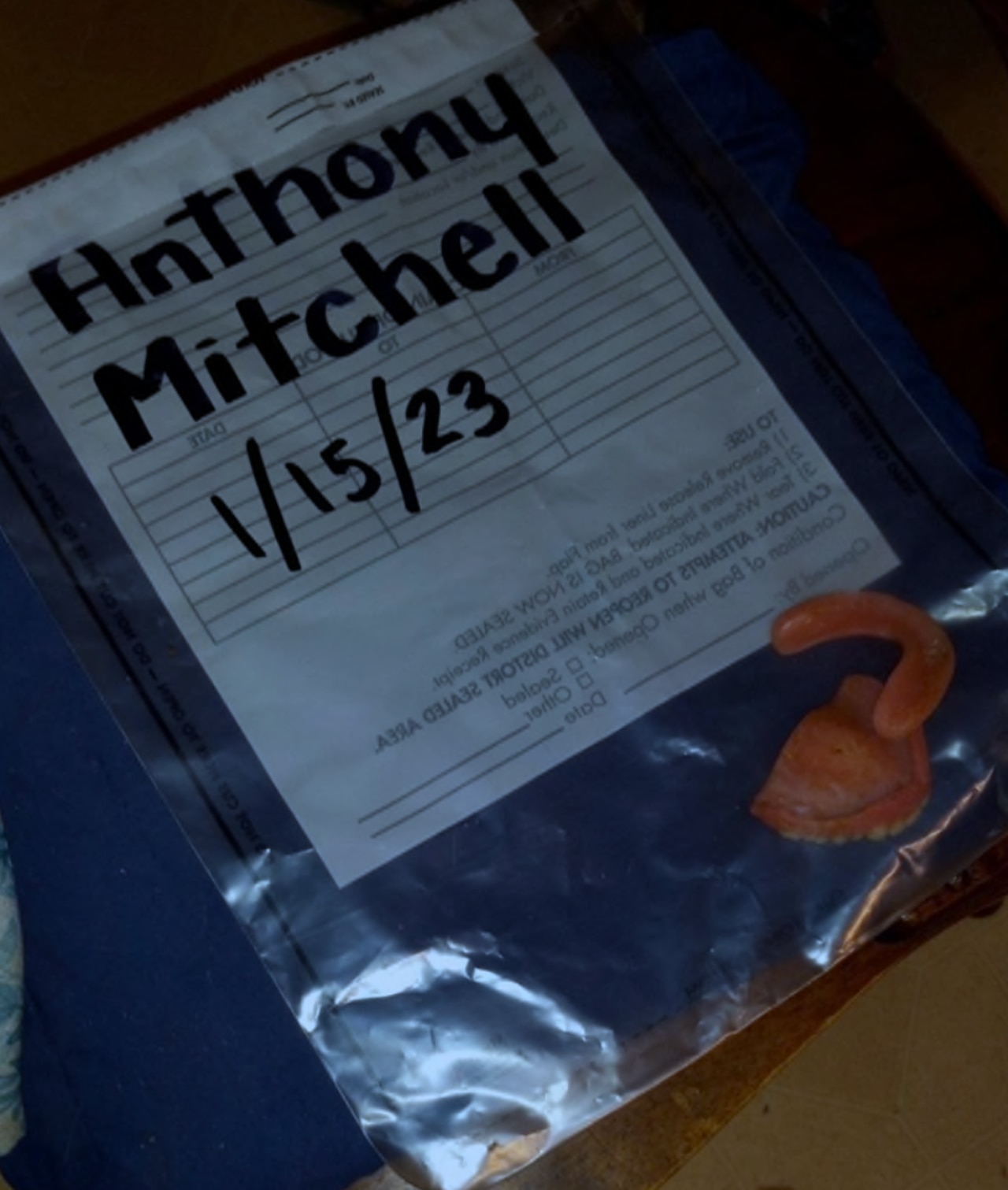

Anthony Mitchell’s body temperature was 72 degrees last month when Walker County deputies finally dragged his hypothermic body to the emergency room. He’d been arrested two weeks earlier, delusional and unwell, but apparently got torture instead of treatment at the hands of Walker County law.

“It is difficult to understand a rectal temperature of 72,” an ER doctor wrote in Mitchell’s file.

It is difficult to understand any of it, to process the horrors described in lawsuits, or in stories by AL.com’s Sarah Whites-Koditschek.

It is difficult to process the negligence of a federal prison that allows a mentally ill man to die in a hot room, his face stuck to the window where he took his last breath trying to suck a little cool air.

It is difficult to process the bulk of a whole Walker County Sheriff’s department ignoring inhumane, and ultimately deadly treatment of a mentally ill man.

It is less difficult, though, if you’ve paid attention to how much of this country, and Alabama specifically, treats mental illness and incarceration.

Hundreds of Alabama inmates, many of them mentally ill, died in custody between the deaths of Rutledge and Mitchell, and we have normalized inmate deaths so thoroughly that most of us barely notice.

Hundreds more died in federal prisons in that time, and across the country thousands – more than 10,000, if previous patterns held – died in state prisons.

The number of drug or alcohol-related deaths in state prisons across the country rose 623% from 2001 to 2019, from 35 to 253, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Suicides rose 85%, and homicides 267%.

More than 40 percent of people in state prisons and local jails nationally have been diagnosed with a mental disorder, according to the non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative. Two-thirds of those in federal prison and three-fourths of those in state prison got no mental health care while locked up.

Yet in Alabama – we are not alone in this, by the way – we have punished the mentally ill and addicted in most every way possible. Data shows those two conditions are often related, according to the National Institutes of Health, yet our approach is deadly.

We start from a spot with a basic lack of preventative mental health care, and exacerbate it with failure to expand Medicaid, so those in most need, and among the most vulnerable, can’t afford care at all. So we come to rely on police, rather than trained healthcare workers, to respond to crises.

Get John Archibald’s newsletter

Enter your email to subscribe to John’s upcoming weekly newsletter:

It often ends badly.

So many families are touched by mental illness, as they are by any disease. Who should get help? And who should get jail?

It shouldn’t be political.

Yet doctors say new guidelines for addiction medication – brought to you by the Alabama Legislature – will make it harder for patients to get the effective addiction medication Buprenorphine, meaning they will more likely die on the streets, or be jailed with illegal drugs, which does not solve the problem and costs the state millions.

Our politicians scream “tough on crime,” and put drug offenders behind bars, but our prisons are criminally overcrowded and the parole system as broken as any law.

And now a bill has been pre-filed in the Legislature to put homeless people in jail for longer periods of time.

Prisons cost us millions upon millions, but criminalization is an industry too. For contractors and governments. Departments at every level of the criminal justice system count on money from tickets and arrests to perform their basic function.

Our jails and prisons are warehouses for those we don’t know how to deal with, and offer little in the way of rehabilitation, or treatment. So people die, and suffer, and waste their lives every day.

And we don’t see them. Or don’t see them as people worth saving.

Let the deaths of Tommy Lee Rutledge and Anthony Mitchell be shocking. They should be.

But let them shock us into seeing them as people, regardless of their crimes or mistakes or addictions or illnesses. Let it shock us into seeing the others who died under less extreme, but just as tragic circumstances.

Let it shock us. If it helps us to see ourselves.

John Archibald is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for AL.com.