‘Any hour of the year could bring a tornado,’ Alabama scientist says

Tornado researchers from Huntsville’s Severe Weather Institute and Lightning Laboratories (SWIRLL) are in Memphis today for the kickoff of what meteorologists call “one of the largest and most comprehensive severe storm field campaigns” in the country.

It’s called PERiLS (Propagation, Evolution and Rotation in Linear Storms) and it’s funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It will deploy resources from a dozen top atmospheric research centers to areas “from the Missouri bootheel southward to the Gulf Coast and from the mid- and lower-Mississippi Valley eastward to the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains.”

It’s called Dixie Alley, and the research team at the SWIRLL, a University of Alabama in Huntsville laboratory, is part of the 12-member team of storm experts deploying across the region. South and east of the traditional Tornado Alley in the Midwest, Dixie Alley includes Alabama where weather can produce long-track, violent tornadoes especially in Spring. The scientists aren’t going to chase storms. They’re going to set up networks and observe what the weather does.

“The computer models are getting better,” UAH professor and SWIRLL Director Kevin Knupp said Tuesday. “They’re better at reproducing the the expected conditions for a potential severe weather event.”

The laboratory at UAH “is well positioned to continue to really spearhead that research,” research scientist Ryan Wade said. “We’ve really been focused on helping to bring light to … the unique problems that are associated with warning (about) fast-moving tornadoes embedded in lines wrapped in rain at night.”

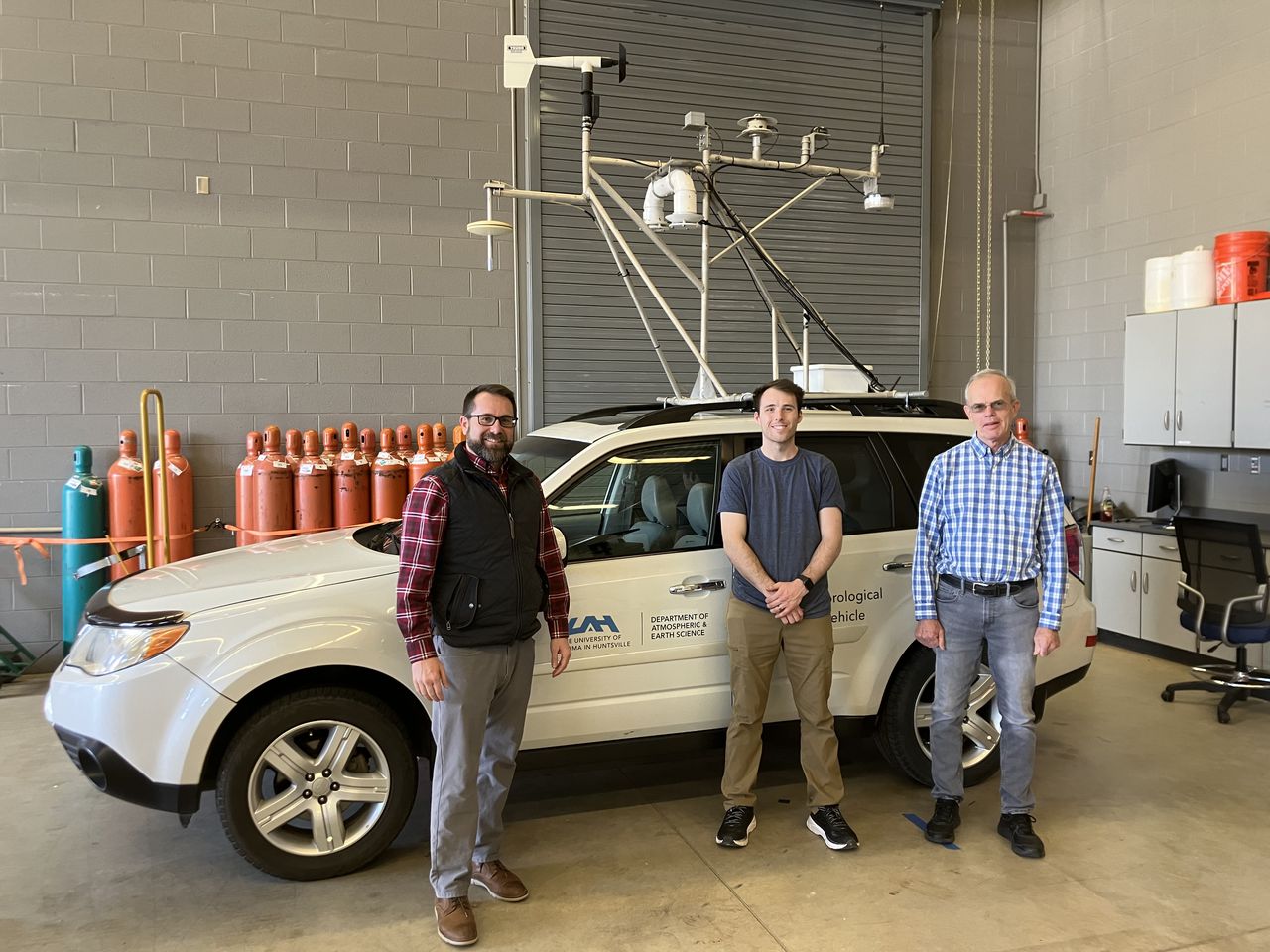

Storm-chasing University of Alabama in Huntsville instructors pose before a roving tornado and storm chaser full of tracking and measuring gear. From left are Research Scientist Ryan Wade, Research Associate Preston Prangle and Professor Kevin Knupp. Spring is one of Alabama’s most active tornado seasons, but the scientists say storms can happen in the South any day of the year.

“We’re getting a better idea about the variability in how rapidly the environment changes immediately ahead of the squall line,” Wade said. “Quasi-linear convective system is the technical term. I like the more common term ‘squall line.’”

“It can be that we’re relatively cool and rainy and you don’t think it feels like tornado weather,” Wade said, “but immediately out ahead of the line, you get this surge of moisture that sometimes help feed the instability. You get this acceleration in winds that helps produce that stronger spin.”

Wade and Knupp say scientists are getting a “little bit better handle” on how tornado friendly environments evolve. They know the sheer number of tornadoes in the Southeast is up from 20 years ago.

Knupp’s research is centered on the “boundary layer” around the storms in the lower atmosphere. The shorthand for that work is PERILLS which stands for “propagation, evolution and rotation in linear storms.” Knupp agrees with Wade that the common phrase for these linear storms is “squall line.” What makes the Southeast unique for tornado research is that “any hour of the year could bring a tornado here” in Knupp’s words.

“We are gradually improving the numbers, improving lead time,” Knupp said of warnings. “A unique characteristic of our cool season events is they’re really shallow,” he said. “That means that radar won’t detect the relative circulations if they’re too far away.”

Knupp said he had a student study a weather event caught by radar at the Huntsville International Airport Jan. 1, 2022. “The ARMOR radar out there was right on it. It was only 5 or 10 kilometers away,” Knupp said. “It clearly showed a well-defined circulation. But the Hytop Radar (east of Huntsville) really didn’t see anything. Nor did Columbus (Miss.) to the west.

“That was an example of one of those shell systems that had a good signal close in, but the distant radars didn’t see the circulation well at all,” Knupp said. “So, you have to key in on other things to fill in that information gap.”

What does this weather scientist do to protect himself at home? “I’m watching RadarScope,” he said of a popular weather app. “And if I have to take cover, I’ll take cover.” Knupp doesn’t have a storm shelter at his home, but he’s thinking about adding one. In-ground is better, he said, but “either one would be much, much better than having nothing at all.”

No conversation about tornadoes in Alabama would be complete without a question about the “polygon,” the tilted box shape National Weather Service forecasters use to warn residents where tornadoes are most likely. “Respect the polygon,” is famous advice from Alabama’s best-known television meteorologist James Spann. Do the research scientists have anything to add?

Some areas in the country “will put up these really large polygon boxes,” Wade said, “because, well, somewhere in there …. (are) all these circulations that are embedded plus strong winds, (so they’re) just going to warn for the whole thing.” National Weather Service offices in Birmingham and Huntsville are better about their polygons, Wade said.

“Fine-tuning the polygons” is one of the big goals of modern weather professionals. “(That’s) so the weather radio isn’t going off while you’re sitting up in Hazel Green and the warning is for south Huntsville and Lacey’s Spring,” Wade said. Look for even more of that tuning in the coming decade, he said.

Will we ever neutralize the tornado threat? “If we could produce weather, we would and we’d be making a lot more money,” Wade said. “Nature is going to do what it’s going to do and all we can do is help with the prediction part.”

That’s the mission of UAH’s SWIRRL laboratory, Wade said. “With all of the equipment that we have and all the expertise that we have, we’re really that leading severe weather research university and institution focusing on Southeast weather.

“We’re focusing on the problems of our people and the unique environments here and we feel like we’re position to really focus on the unique tornado changes that we have here in Alabama,” Wade said.