Alabama’s parole rate more than doubled in 2024: ‘Accountability has changed things’

After a year in the public spotlight, the head of the Alabama parole board once again chose to say nothing.

“Any questions will have to go to Matthew (our spokesperson),” said Leigh Gwathney, the chair of the board, after a handful of parole hearings on a cold Thursday morning in December.

AL.com attempted to ask the three board members why they had started letting more people out in 2024 — even if it was most often on a split vote. Gwathney still remains a reliable ‘no’ vote, but the other two members have been voting yes and paroling people nearly three times as often this year.

Gwathney didn’t let the other two board members answer, either.

“Come on,” a security guard said softly, ending any questioning.

That morning, Gwathney had just voted to deny two paroles — both for men convicted in drug cases. Her colleagues disagreed, thinking both men deserved a shot at life outside of prison. Both were paroled.

Gabrelle Simmons and Darryl Littleton, Associate Members of the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, and Leigh Gwathney, Chair, listens to supporters of offenders during a hearing at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama, January 9, 2024. Tamika Moore | AL.com

That’s how it’s gone most of this year, as AL.com spent 2024 delving into Alabama’s broken parole system, a system that had all but stopped releasing eligible prisoners in 2023. Last year the parole rate fell to just 8% – despite the parole board’s own criteria showing about 80% of the eligible inmates should be let out. The chairperson even denied parole to a quadriplegic inmate who couldn’t speak and denied another inmate who had died a week earlier.

As the reporting continued, the broken system began to change:

- Two of the three parole board members began to change their voting patterns, opting to let more people out of prison.

- Alabama’s parole rate rose to 20% in 2024, according to data from the Bureau of Pardons and Paroles. That comes out to roughly 250 more people getting out of prison this year than in 2023.

- Criticisms and concerns poured in from both sides of the aisle. In a rare move, two former chief justices, one Democrat and one Republican, separately went to Montgomery and argued with the board chair over who should be released.

- Lawmakers held hearings and demanded answers. They said reporting increased public scrutiny on an issue lawmakers were already tracking. “This sort of accountability has changed things,” Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, said this summer.

In the downtown Montgomery parole building that same day, several Alabama lawmakers piled into the room to watch some of the final hearings of the year. They sat quietly on a back row, some watching the dais while others looked around the room. They called no attention to themselves.

‘I’ve tried everything’

The Joint Prison Oversight Committee’s appearance at the parole board that morning in December wasn’t the first time the committee scrutinized the agency this year.

In July, at a regularly scheduled meeting, the committee heard from family members of people locked away in prisons across the state. For 90 minutes, they heard accounts of deaths, rapes, assaults, and extortions behind bars.

Those stories included parole denials.

One mother asked why the Alabama parole board wouldn’t let anyone out, including her son.

“I’ve tried everything I can… you can’t get nowhere because once they put you in there, they throw the key away,” Karen Gann said. “You’re stuck for life.”

Another woman said her brother is on work release and spends his day in the community without supervision but has been denied parole five times. “We don’t understand why and what’s the problem,” she said.

The front entrance to the Alabama Bureau of Pardons & Paroles as pictured in May 2024, in downtown Montgomery, Ala. File photo

Rep. Jim Hill, a former judge and Republican from St. Clair County, told the room that the legislature doesn’t control the parole board, nor the prison system. “We can offer suggestions, we can do some things that perhaps call certain things to their attention… But the day-to-day operations of the parole board are not supervised, they are not directed by the legislative branch of government.”

“Pardons and paroles ought to be here… to hear what you have to say,” he added.

Packed prisons

Alabama’s prisons are notoriously overcrowded, fueling what the federal government calls unconstitutionally dangerous conditions. In fact, state prisons are facing a lawsuit from the Department of Justice for being cruel and unsafe, challenges coming under both Republican and Democrat administrations.

And the bottleneck at the Alabama Parole Board is not helping the problem.

AL.com’s reporting found:

- Alabama used to parole most eligible inmates, but the board began to stop nearly all paroles when Gwathney took over as chair in 2019

- The board often denies parole to people who are already safely working in fast food and warehouse jobs – sometimes for years

- Many of the denied are serving out decades-long sentences under three-strikes laws that no longer exist.

- The prison system itself has to use medical furloughs instead of depending on parole to send dying, elderly inmates home

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall, the state’s top law enforcement officer, said in 2021 that the people in state lockups needed to be there, and there was no one left to reform.

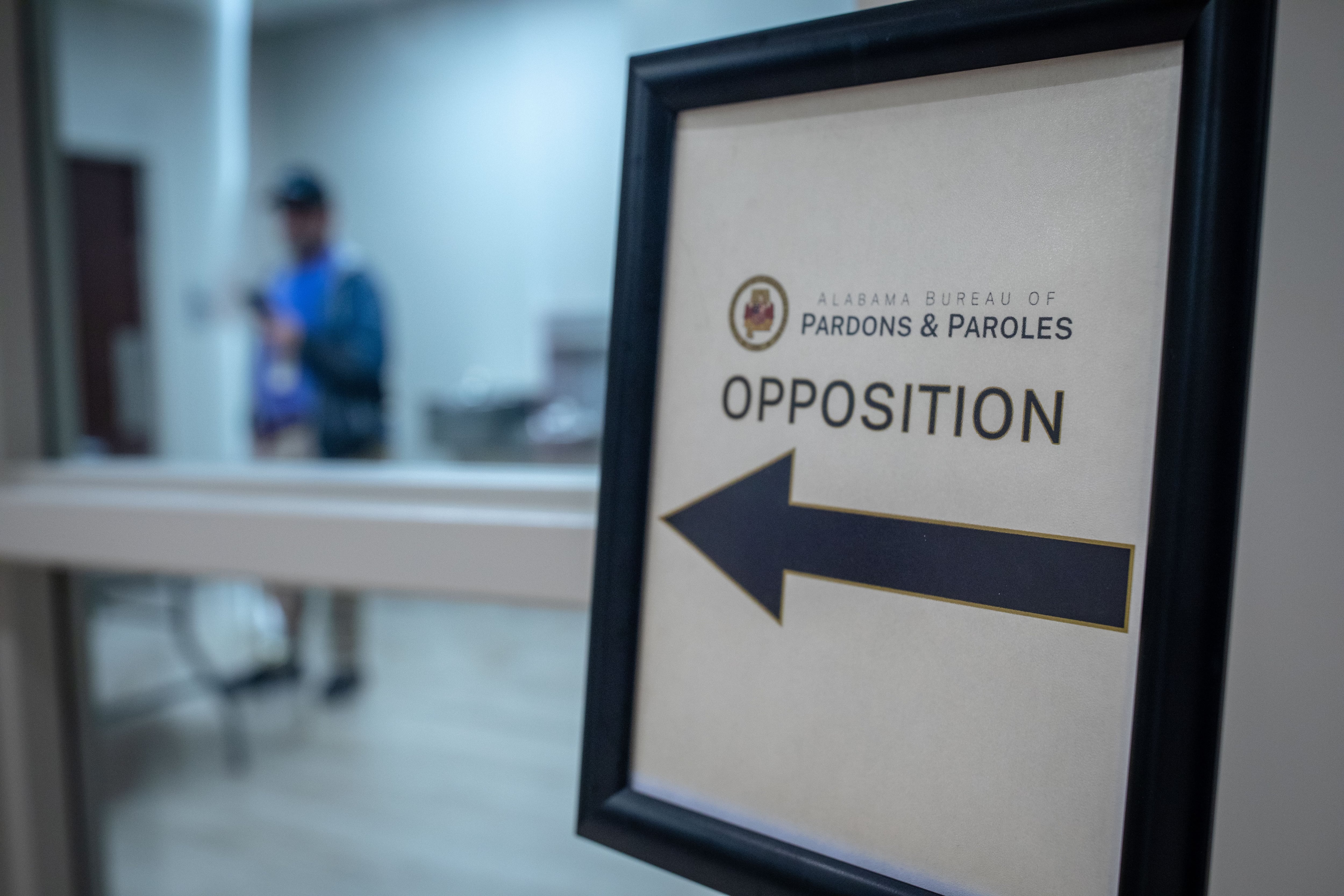

And while inmates cannot attend their own parole hearings, Marshall’s office doesn’t miss a hearing. He has a representative oppose parole at nearly all hearings conducted publicly.

The opposition waiting area of the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama, January 9, 2024. Tamika Moore | AL.com

To test Marshall’s theory, AL.com ran a series of stories about individuals who had been denied parole. Their stories included a man who went back to prison indefinitely for missing a meeting; one who was deemed safe enough to serve ice cream at a beach restaurant but not to go home at night; one who gets passes to leave prison on the weekends but can’t seem to get paroled; one who stole a nail gun from Lowe’s; and more.

As the series ran, nonprofits took an interest. Lawyers volunteered to represent people featured on AL.com, online fundraisers helped raise money for legal defense, community organizations hosted forums that revolved around paroles and law schools asked for guidance in training their students.

During rehearings throughout the year, on a split vote, the board even released two prisoners featured on AL.com for their past denials. None of the others profiled had hearings set for this year.

When asked in the spring if Marshall still stood by his comments or had anything to add to the parole conversation, a spokesperson said, “We do not have anything further to add as we disagree with the premise of every article you have written on the topic.”

The same spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

Marshall’s office has a longstanding relationship with VOCAL — a nonprofit victims advocacy group, which stands for Victims of Crime and Leniency. Like the attorney general’s office, the group speaks against parole at many hearings, even when the victim’s family doesn’t oppose release, even when some families don’t want them to speak for their loved ones.

The Alabama Attorney General’s Chief Counsel, Katherine Robertson, is a member of the VOCAL board, and a spokesperson for the office previously said, “It is a proud tradition of the Attorney General’s Office to partner with VOCAL to ensure that Alabama’s crime victims continue to have a voice.”

Contentious meeting

After the prison oversight committee called out the board for not attending in July, all the three parole board members showed up to the next meeting in October. This time, Chairperson Gwathney took that same podium where family members had complained about the board and their decisions.

“It can be looked at that we are only looking for one side of things,” Gwathney said. “That could not be further from the truth.”

Gwathney told lawmakers that the board “believes in transparency.”

During her testimony, she detailed the criteria for deciding who to parole. But according to the board’s data, they only follow their own guidelines about 20% of the time. And when asked about those guidelines, data and methodology, Gwathney said she didn’t know the definitions for a certain set of their data.

“Madam chair, that is problematic,” said the committee’s chairperson, Sen. Clyde Chambliss, R-Prattville.

The meeting grew contentious, with several lawmakers shaking their heads as Gwathney attempted to answer questions.

England, who also sits on the committee, told the former prosecutor that her testimony wasn’t persuasive.

“You inadvertently made the case that the board needs oversight,” England told Gwathney.

“People want justice. They want bad people to stay in, they want people that are worthy of parole to get out.”

Former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore

That meeting also included a back-and-forth between Gwathney and Chambliss over questions that the lawmakers had asked in January but still hadn’t received answers to. Chambliss told Gwathney she had until the end of November to get those answers.

“That’s why we are frustrated,” Chambliss said.

“We asked specific questions. We want specific answers.”

‘Tough world out there’

Gwathney, a former prosecutor in both the Alabama Attorney General’s Office and the Jefferson County District Attorney’s Office, voted no in the cases featured on AL.com and hundreds more.

Yet, her counterparts Darryl Littleton and Gabrelle Simmons have begun freeing more people on parole through 2-1 votes. While Gwathney is chair of the board, her votes do not weigh more heavily.

Gwathney, who was appointed to the board in 2019, often seeks to put off hearings and send inmates back to prison for another five years — the maximum time allowed by state law.

Gwathney’s term ends in the summer of 2025, but she could be reappointed by Gov. Kay Ivey.

Leigh Gwathney, Chair of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, listens to an offender ask for a pardon during a hearing at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama, January 9, 2024. Tamika Moore | AL.com

Former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb founded a legal group to help elderly or sick inmates get parole. And when Gwathney denied one of Cobb’s clients who was locked up on a property crime and who became totally incapacitated in prison, Cobb drew the line.

“I am convinced that the public should know that the chairman of the parole board voted to deny the medical parole of a nonviolent offender who is a quadriplegic, completely bedridden, and spends most of the day in a catatonic state,” said Cobb.

“I don’t know how she sleeps at night.”

The chairwoman has not responded to requests for comment throughout the year from AL.com. And when approached for this story after public hearings, Gwathney said all questions needed to be sent through the agency’s communications director, Matthew Estes.

Those questions were sent and received by the director, who forwarded them to Gwathney and the other parole board members.

They did not respond.

However, Gwathney did stop one hearing in the summer to directly address AL.com. When giving her typical speech after hearings before the board begins silently deliberating, she addressed AL.com, saying “it’s important to us that everybody that comes to parole hearings knows that we don’t just show up here and listen and decide who we think did a better job of arguing their case, because that would be an absolute horrific injustice to everybody involved.”

“It’s oftentimes reported that’s what we do. That we show up and we make a very quick two-second decision and that is the furthest from the truth.”

She talked about how the board’s files are secret, but many people write to them instead of showing up.

“Well, I bet AL.com can imagine that it’s a tough world out there, right?” Gwathney said in the public hearing.

“People can’t afford to put gas in their cars. You all started having somebody come more often, and I’m glad for that. And I hope that you all remember that it’s tough. It’s tough for folks to come to these hearings.”

The inmates

Even the prison system has to work around the entirely separate parole board. While John Hamm, the Commissioner of the Alabama Department of Corrections, didn’t comment on the board publicly at that meeting in October, he did detail the status of the prisons and the efforts to hire more people to staff them.

This year, Hamm has used his power as commissioner to release a handful of people who had been denied parole, granting them a special release known as medical furlough. Only extremely sick people who meet a slew of conditions can get the status, and it’s designed to let those who are gravely ill die at home.

So far in 2024, eight inmates have been granted medical furlough. At least five had been recently denied parole.

Will Tucker, the southern director of a nonprofit called Jobs to Move America, said it’s time politicians take up the issue of parole in Alabama. The group is dedicated to improving working conditions and ensuring fair pay for all workers — including inmates.

Tucker said it’s “absurd” that Alabama declines to parole hundreds of prisoners who are on work release, who leave prison five or six days a week for regular jobs at McDonald’s and KFC and Burger King and warehouses and government offices.

Right now, Alabama has 3,000 inmates who are cleared to work outside. Many have been denied parole.

And while they continue to work in the community and go back to sleep in prison, Alabama collects 40% of each paycheck to help pay for their lockup.

“Finding a way to get the incarcerated workers in work release out of prison fully should not be a controversial task,” Tucker said.

“And if you really want to address problems with overcrowding and understaffing in Alabama as a policymaker, you would look for a way to make that happen.”

‘Sunshine is the best antiseptic’

During the last legislative session, lawmakers introduced five bills to reform the parole board.

England, the representative from Tuscaloosa, introduced a bill that would have allowed inmates to attend their own hearings and appear virtually. He introduced three others, too. The second would reduce the power of any single vote by increasing the number of parole board members from three to five.

His third bill sought to create a council to develop a new risk assessment for those up for parole and develop a process for inmates to appeal if they met the state guidelines but were denied anyway. He’s already prefiled that bill for the 2025 legislative session, which starts in February.

England’s other bill called for inmates 60 and older who are denied parole to be given a detailed plan on how to improve their chances for their next hearing, and had other provisions for inmates seeking medical release.

In 2023, 10 people 80 years old and above were up for parole. Each was denied.

This year, eight people over the age of 80 had parole hearings. And this year, two were granted.

A fifth bill during the last session, sponsored by Sen. Linda Coleman-Madison, D-Birmingham, sought to require the board to restore voting rights for certain people who meet the criteria.

All five bills failed to pass. But in 2024, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle began to acknowledge there was a problem with paroles in the state.

Former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore appeared at the parole board this summer in support of a man who was spending his life in prison for stealing a nail gun from a Lowe’s store near the beach years ago.

“People want justice. They want bad people to stay in, they want people that are worthy of parole to get out. That’s the system,” Moore said at the time. “That’s what it’s supposed to be. But that’s not what it’s been.”

“What it’s been is a representative of the attorney general’s office controlling the parole board in my opinion.”

After fighting for that man, Willie Conner, for several years, Moore saw Conner paroled on a 2-1 vote. The former judge got into a lengthy back-and-forth over the letter of the law with Gwathney during the hearing. Eventually, Gwathney voted to keep Conner behind bars.

Moore is a Republican. Cobb, who once held the same office as the head of the Alabama Supreme Court, is a Democrat. And yet the two agree on this issue, as Cobb also went before the parole board and argued with Gwathney this year.

Cobb appeared in April on behalf of Robert George, an 85-year-old man who was serving a life sentence for firing a gun during a gathering in 1993 and accidentally killing a young girl.

The face of Robert George at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama. He one of many who were denied of parole in Alabama. Photo Illustration by Tamika Moore | AL.com

Gwathney grilled Cobb and her colleagues, questioning how a mother could come to support parole of a man who shot her daughter.

“What kind of home did she live in?” Gwathney asked about the victim’s mother.

“Have you done any kindnesses for her the past year?”

“How many times did you initiate conversation? What percentage?”

“Who was there when she signed the affidavit?”

George was, after a lengthy hearing, paroled. Gwathney voted no.

Not long after his release, George died.

“There’s an old phrase that sunshine is the best antiseptic,” Cobb said previously. “The sunshine that AL.com has brought upon the decisions by the Alabama parole board chair exemplifies this old adage.”

Cobb continued to win parole for often elderly and sick inmates through her work as the executive director and founder at the nonprofit legal center Redemption Earned. Late this year, she stepped out of the role, and former Jefferson County Circuit Judge Teresa Pulliam took over.

And it wasn’t just lawyers and politicians and people with loved ones inside who worked to create change in 2024.

During the Alabamians for Fair Justice Lobby Day this spring, about 60 people showed up to walk the halls of the Alabama State House and talk to lawmakers about parole reforms. Cumberland School of Law enacted a parole clinic in partnership with Redemption Earned. A free event about criminal justice from PARCA, a state nonprofit think tank, shifted into an hourslong public talk on the parole board this spring. And law students from across the country traveled to Montgomery, volunteering their time to represent people seeking a shot at freedom.

Carla Crowder, a lawyer and the executive director of Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, said she’s generally hopeful about the rise in parole rates this year.

But, she doesn’t think it’s high enough. She said too many people still languish in Alabama prisons for too many years on old charges.

“People are being denied based on their crime of conviction, which might have been 25, 30, 35 years ago,” she told AL.com, “and not based on extensive records of rehabilitation and lack of dangerousness when they get out.”

A flurry of lawsuits

In 2023, the board ended the fiscal year with an 8% parole rate — the lowest in more than a decade.

But in 2024, the board’s September data showed they ended the fiscal year with a 20% parole rate. There were 2,221 parole denials in the fiscal year, with 565 grants.

That’s despite the board’s own guidelines showing 83% of the eligible inmates should be paroled.

Lauren Faraino, a lawyer who founded a nonprofit organization that represents inmates called The Woods Foundation, often appears at the parole board. She also represented George, along with Cobb’s organization.

“The Alabama Parole Board remains a glaring tool for perpetuating the outdated and exploitative system of convict leasing in our state,” Faraino told AL.com.

Inmates sit in a treatment dorm at Staton Correctional Facility in Elmore, Ala., Wednesday, Sept. 4, 2019. AP Photo | Kim Chandler

She is one of several lawyers representing inmates who are suing the state in federal court over what they call labor trafficking for holding prisoners in work-release centers and taking a chunk of their paychecks.

She said that parole in the state has been “effectively shut down” for years and the elevated rate is making up “for the thousands of people who were unjustly denied in years past.”

Two of the board members, Littleton and Simmons, list their training in risk assessment and re-entry on their state web pages, along with their professional associations in national parole groups. Gwathney’s page has no information on training or associations and, while a spokesperson said he asked the chairwoman for that information, she never responded.

“It is somewhat encouraging to see that two members of the parole board appear to genuinely prioritize public safety in their decision-making,” Faraino said. “However, it is clear that Leigh Gwathney is not one of them.”

“She seems singularly focused on fulfilling a mandate to keep as many individuals incarcerated as possible, regardless of the evidence demonstrating their readiness for release.”

Arthur Charles Ptomey Jr. has been repeatedly denied parole, and he’s long since stopped waiting on the parole board to change their practices.

He has been in prison for almost 18 years on third-degree burglary and robbery charges. He’s spent the last six in work release, going back to sleep behind bars at night, and going home on occasional weekend passes.

“I can only keep doing what I’m doing,” he said. “Really, it’s just that my time is in the Lord’s time. It doesn’t have to do with man or the parole board.”

But for others, the new voting patterns this year changed their lives.

The face of Kenneth Wayne McCroskey at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama, January 9, 2024. Photo illustration by Tamika Moore | AL.com

Kenneth McCroskey missed a meeting and was sent back to prison in 2019 to serve out a life sentence handed out under the old three strikes law. He was denied parole last year. But the board reheard his case in May.

This time, by a split vote of 2-1, he got out.

“It’s surreal,” he said.

This project was completed with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures.