Alabama’s billion-dollar prison plan does not end the overcrowding

Alabama is set to spend close to $1 billion on a new prison near Montgomery and is planning to spend at least $600 million more to build a second mega prison by 2026. But the new construction likely won’t end the state’s legal problems with overcrowding.

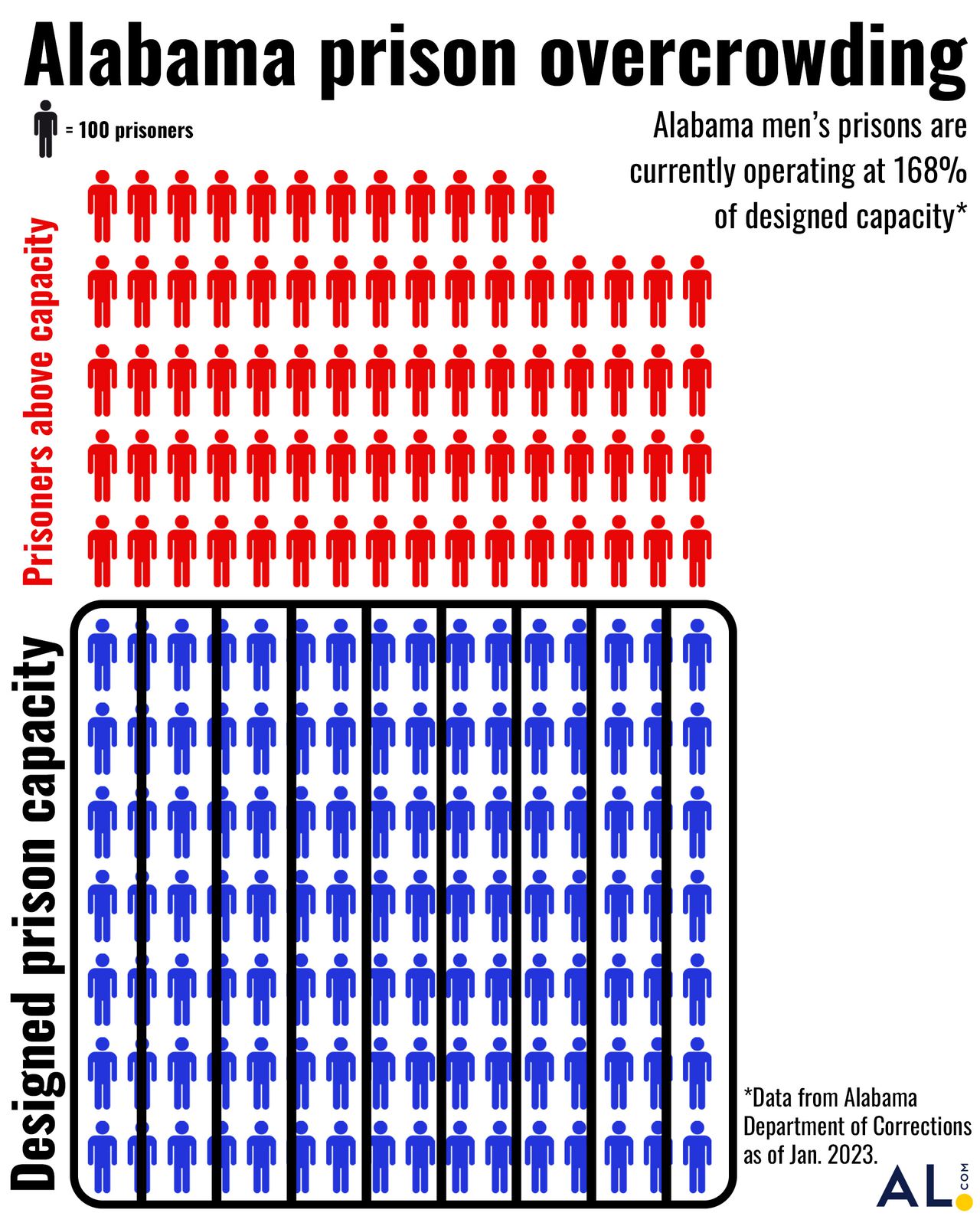

There were nearly 19,000 male inmates in Alabama correctional facilities as of January, in buildings designed to house just 11,000. That means the state’s prisons are operating at 168% of capacity, with one of the highest incarceration rates in the entire world.

Alabama’s prisons were operating at 168% of their designed capacity as of January 2023. | Graphic by Ramsey Archibald

As the two new men’s mega prisons open, the Alabama Department of Corrections will close four older, overcrowded prisons and move those inmates to the new buildings. After all of the shuffling of inmates and staff, Alabama will wind up with more prison space overall. However, unless the number of inmates drops suddenly, the state system will still be well over capacity.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Alabama in 2020 over what they called overcrowded and dangerous conditions. The Justice Department cited failure to protect prisoners from inmate-on-inmate violence and sexual abuse, failure to protect them from excessive force by staff, and failure to provide safe conditions of confinement.

The Legislature and Gov. Kay Ivey agreed on the plan in October 2021 to build two new men’s prisons, one in Elmore County and a second in Escambia County. Each new prison is designed to house 4,000 inmates.

Despite the plan, Alabama remains on track to face trial against the U.S. Department of Justice next year. In the federal government’s 2019 letter to the state, the Department of Justice said that building new prisons wouldn’t solve Alabama’s prison crisis.

“While new facilities might cure some of these physical plant issues, it is important to note that new facilities alone will not resolve the contributing factors to the overall unconstitutional condition of ADOC prisons, such as understaffing, culture, management deficiencies, corruption, policies, training, non-existent investigations, violence, illicit drugs, and sexual abuse. And new facilities would quickly fall into a state of disrepair if prisoners are unsupervised and largely left to their own devices, as is currently the case,” said the letter.

Alison Molman, ACLU of Alabama’s senior counsel, said a mega redesign isn’t the solution to Alabama’s prison woes. “The DOJ couldn’t have been more explicit when they told Alabama… this wouldn’t be proceeding towards a trial if Alabama’s new prisons were enough,” she said.

Once the new men’s prisons are opened, Kilby, Staton, Elmore and eventually St. Clair Correctional Facilities will all close, according to legislation. Those four prisons were designed to hold a total of around 2,500 inmates.

Designed capacity of the new prisons is roughly 4,000 each, according to the Alabama Department of Corrections, which means the plan will result in a net increase in designed capacity of roughly 5,500 for the state.

But that would bring the designed capacity of all men’s prisons in the state to just 16,691. The system already housed 18,839 prisoners this January.

[Can’t see the chart? Click here.]

If the new prisons opened today, the current numbers would mean an occupancy rate of 113%.

Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm said recently that the expectation is that once the new prisons are completed and older ones are closed, there won’t be any net gain in the number of prisoners that can be housed.

He said that could change depending on projections of the prison population and decisions made by a repurposing committee that is studying options for the use of some of the state’s older prisons. But, he said, the new prison designs will allow better management of the inmate population than the existing prisons, which mostly hold inmates in large dorms that have housed as many as several hundred in a single room. The new prisons will have more individual cells.

“Just in round numbers, we have about 80 percent dorms now, 20 percent cells,” Hamm said. “We’re going to have about 70 percent cells and 30 percent dorms. So it will be a little bit easier to control.”

But, Molman isn’t convinced. “Converting to cells is not going to make anything safer,” said Molman. “It’s a misconception that cells are going to make everything safer.”

Nearly all of Alabama’s men’s prisons are overcrowded, including the four that are set to close under the state’s plan. Both Staton and Kilby have close to three times as many prisoners as they were built to hold, and the four closing prisons together held nearly 5,000 prisoners as of January, the last month for which data was available.

Alabama has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world. According to data from the Prison Policy Institute, Alabama has the sixth highest incarceration rate in the United States, which itself has by far the highest rate of any nation. If Alabama were its own country, its incarceration rate would be roughly 1.7 times higher than El Salvadore, the next closest country outside the U.S.

[Can’t see the chart? Click here.]

Molman said for cells to be effective in the way the state envisions, there must be working locks– something the DOJ cited several times in its lawsuit as a problem in Alabama prisons. And if prisoners are locked in cells, Molman said, the matchups in roommates could be fatal. “Unless ADOC is going to make drastic changes to how they make housing assignments, they will be just as deadly as the prisons we have now.”

She said that Alabama has an external classification system to determine which prison someone should be housed in. But once someone gets there, the department doesn’t use an internal classification system—meaning an elderly inmate without a history of violence can be housed with a young, violent prisoner.

New prisons aren’t enough to change the culture of violence within Alabama’s prisons, Molman said. She pointed to Alabama’s documented lack of staffing inside correctional facilities.

“One of the problems with Alabama’s prisons is the lack of staffing. Cells are blind spots… when you don’t have adequate staffing, you’re actually creating more dangerous environments.”

She described issues at St. Clair Correctional Facility, a prison that is designed with more cell space than dorms. Several years ago, she said, an inmate had a heart attack inside his cell; although the rest of the inmates were yelling for help, there were no guards nearby. When they finally came to check the cause of the commotion, the man was dead.

Molman said that often when prisoners are in medical distress, other inmates are left to care for them. Videos posted across social media platforms like TikTok show men in Alabama’s prisons caring for their dormmates during overdoses without any prison staffers in sight. Other times, Molman said, inmates are the ones carrying their fellow prisoners to the infirmary in cases of emergencies. She said Molman said incidents like these show how dangerous cells can be, if the persons locked inside can’t get help.

“I’ve heard them described as death traps.”

She pointed back to staffing as a primary issue with the system, another area the DOJ focused on when it sued the state.

Hamm recently announced salary increases for correctional officers as a hiring incentive.

“The issue with DOC is not the pay…the issue is culture,” Molman said. “People don’t feel like they have the support they need in these prisons. People don’t feel empowered to do their jobs and follow the rules because they don’t have the support they need.”

Molman said the state continues to say the new construction will assuage the DOJ, but she doesn’t think that will happen. “The new prisons will be unconstitutional if changes to the culture aren’t made.”