Alabama’s approach toward gambling is raising questions about public meeting agendas

A public hearing before the Alabama State Senate Tourism Committee was never listed on a meeting agenda, nor was a bill pre-advertised for a possible vote.

But a hearing still took place on Wednesday, creating confusion among lawmakers perplexed that no specific legislation had been presented to them for consideration on the high-profile issue of gambling.

“This is not good government when you bring a bill 140 pages long and no one has seen it and expect us to vote on it,” state Sen. Andrew Jones, R-Centre, said, referring to substitute legislation senators are considering to the Alabama House’s gambling bill that was approved on Feb. 15.

The chaotic meeting might’ve underscored Alabama’s long struggle in crafting a gambling bill, but it is also raising new questions over the handling of a public meeting one week before national Sunshine Week that is recognized each year by journalism and civic groups to highlight the importance of open government and meetings.

The Tourism Committee’s concerns focused on the lack of a requirement in Alabama law for any public body to require a detailed agenda, especially on high-profile matters.

“Regardless of legal nuances, we should step back and talk about what is right,” said David Cuillier, director of the Joseph L. Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the College of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida.

“Clearly, it’s important the public be apprised of the important issues before they are discussed, so people have a chance to participate and observe,” he said. “If we don’t have that, we don’t have much of a democracy.”

Meeting fallout

Alabama State Senator Chris Elliott, R-Josephine (John Sharp/[email protected]).

The meeting’s fallout has some lawmakers concerned over the public turning its back on any gambling measure that could be voted out of the Legislature. Voters would be required to adopt a constitutional amendment legalizing any form of gambling – casinos, lottery, or sports betting – if legislation is approved in both chambers.

“In my time in public office, I have never seen a meeting notice with no bill on the calendar but a public hearing taking place on the thing that wasn’t there,” said State Sen. Chris Elliott, R-Josephine, a committee member. “Some of my colleagues might not think about this, but if we feel like the legislation is in a good spot, if the public doesn’t feel good about the process, it might undermine their trust on what passes the Legislature.”

He added, “You still need the public’s buy-in and understanding what decisions were made and why.”

Some lawmakers, reached late last week, said they were not overly concerned over the dysfunctional committee meeting that resulted in a public hearing filled with general statements about gambling.

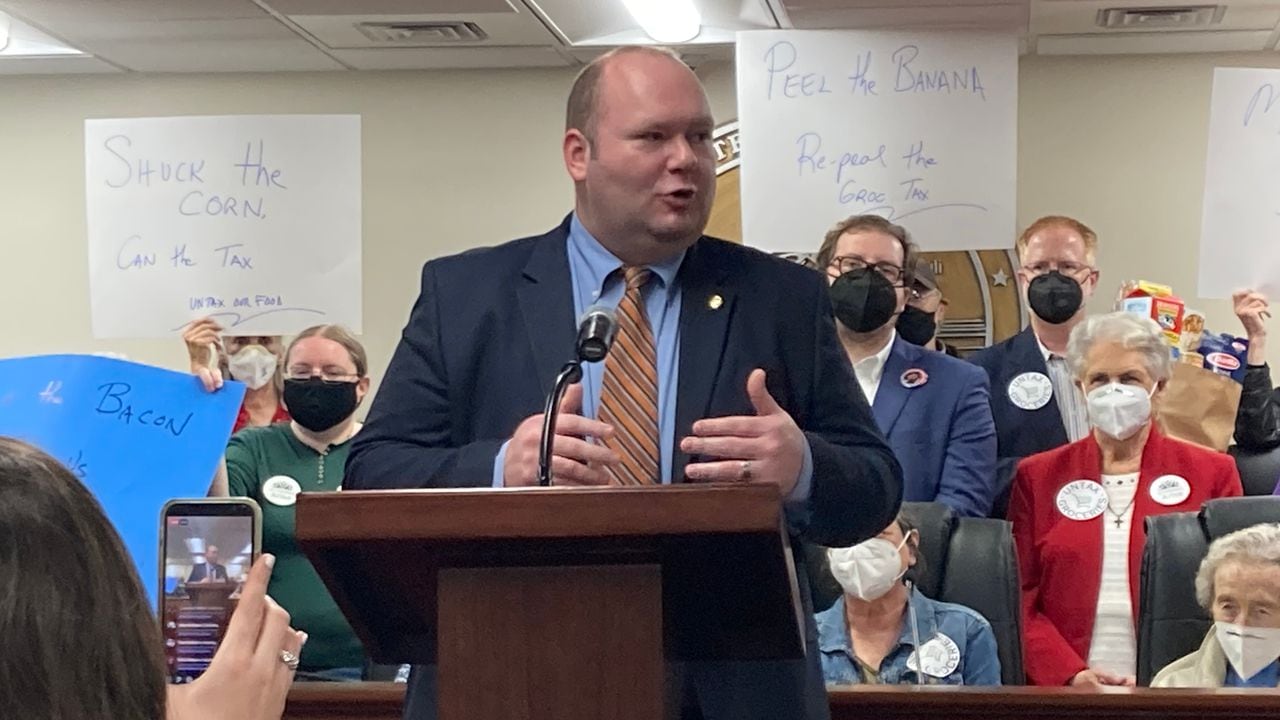

Alabama state Sen. Andrew Jones, R-Centre, speaks at an Alabama Arise rally on repealing the state sales tax on groceries. Jones is sponsoring a proposed constitutional amendment that would repeal the tax if approved by voters. (Mike Cason/[email protected])

Jones, critical during the meeting of how the gambling bill was being handled, told AL.com late last week that he is confident in the process going forward.

“The public has been very engaged and involved long before this bill even came up to the Senate, and I believe that constituent involvement is critical to the process,” Jones said. “And at the end of the day, the public will have a final say at the ballot box should this bill make it over the finish line.”

Sen. Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro, who said it was “unfair” for the committee to host a public hearing before a proposed gambling bill was reintroduced, said the meeting was held within the legal bounds of Alabama law.

He also said that the committee’s chairman — Sen. Randy Price, R-Opelika – had “no intention of doing anything underhanded” and was dealing with other variables that were outside his control at the time. Price did not return a call for comment.

Alabama State Senator Greg Albritton of Atmore speaks during a candidates forum in Mobile. The Republican candidates seeking the Congressional District 2 nomination spoke before a group of GOP voters on Monday, Jan. 15, 2024, at the Marriott Hotel in Mobile, Ala. The forum took place 50 days before the March 5, 2024, primary election in Alabama.John Sharp/[email protected]

Sen. Greg Albritton, R-Atmore, said at the time of the meeting, there was a “substitute” gambling bill coming “off the presses,” and one that would replace the House versions. The House version is a comprehensive gambling package that creates a lottery, authorizes casinos in up to seven designated locations and approves sports betting.

“We didn’t know what to put on the agenda, frankly,” Albritton said, adding that he was in favor of approving the House versions to “keep the process moving along.” The committee opted to not do that.

Other Senate Republicans, who have a supermajority status in the chamber, say the House version does not have enough support.

“The issue is what the House passed, whether you like it or you don’t, simply cannot pass the Senate,” said Elliott, who anticipates the Tourism Committee considering a new gambling version when it next meets. As of Monday afternoon, the Alabama Legislature’s website was not advertising a Tourism Committee meeting this week.

Albritton said the public hearing at last week’s meeting revealed little of substance, adding that the issue has been well-discussed and debated for years.

“We’ve had so many public hearings that we know who believes in what,” Albritton said. “I don’t think the public hearings are worthwhile. We just need to do the job that we have.”

Requiring transparency

Gambling is considered one of the Legislature’s biggest ticket items this spring session and all eyes are on how lawmakers handle the process of crafting the bill.

Evans Bailey, an attorney for the Alabama Press Association, said the Senate committee is allowed to make its own rules regarding meeting notices. He said the state Senate has rules established that do not require detailed agendas, though he would like to see that changed.

The Alabama Constitution of 1901 allows the Alabama House and Senate to set its own rules when it comes to public access to and prior notice of all sessions and committee meetings.

“Requiring more transparency in public notices would be beneficial for all, including legislators, because it would avoid the pitfalls of legislating by surprise,” Bailey said.

Alabama’s Open Meetings Law also does not require detailed meeting agendas for city councils, county commissions, school boards, and other public bodies throughout the state. The law requests that any preliminary agenda be posted as soon as possible in the same format as a meeting notice, which is required. If a preliminary agenda has not been created, the notice must include a “general description of the nature and purpose of the meeting.”

In 2010, the Alabama State Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s ruling that allows a government body to discuss matters that are not included on a preliminary agenda. In that case, a 2008 decision by the Alabama State University board of trustees to remove the named, “Joe L. Reed” from the Acadome in Montgomery occurred despite it not being listed on the meeting’s agenda.

“Perhaps unfortunately, Alabama law allows issues not in the formal agenda to be raised and voted upon,” a trial judge wrote. “However distasteful this tactic may have been in this particular instance, there is not substantial evidence that any laws were broken.”

State approaches

Some states do require more from the meeting agendas, according to an analysis by the Reporters Committee for the Freedom of the Press.

Some examples:

- In Arizona, agendas are required to list specific matters to be discussed, considered or decided during a meeting. Nothing can be added to the agenda once a meeting begins, not even by a majority vote of the public body. And only in cases of an “actual emergency” can an agenda be altered within 24 hours of the meeting.

- In Illinois, a public body cannot act on something not included on the agenda. Though Illinois law doesn’t include requirements for a proper agenda, an appeals court found in 2002 that an agenda simply stating “New Business” failed to provide sufficient advance notice to the public on an action taken on an alternative benefits program for elected county officers.

- In Iowa, “tentative agendas” cannot be amended within 24 hours of a meeting’s start time. Previous court cases have described the adequacy of a meeting notice to be determined “by what the words in the agenda would mean to a typical citizen or member of the press.”

- In Louisiana, a public body cannot take up an item not on the distributed agenda at least 24 hours before the meeting begins except by unanimous vote of the members present. And significant proposals must be identified specifically in the agenda.

In Tennessee, lawmakers recently made changes requiring more details on meeting agendas. Under a Tennessee law approved by lawmakers last spring, the state’s open meetings law requires city and county legislative bodies produce an agenda available to the public at least 48 hours before a meeting that “reasonably describes” each agenda it.

Reality TV

Elliott said in Alabama, there could be issues Alabama lawmakers look at in the future, especially over how the Tourism Committee meeting was handled.

But he also said it’s important for there to be a balance on hosting open meetings for big-ticket items like gambling as opposed to the process becoming “reality TV.”

“Just like with everything else, there is middle ground there and members need to discuss and debate what is going on,” he said. “Of course, you need to have your agendas published. And no, you should not have a public hearing on a bill that is not noticed. The public has a right to know what is going on and provide input into the legislative process, and that’s very fair.

He added, “But it’s not a reality TV show where you can see every legislator eating dinner and going to bed at night. There is a line between that. The public ought to know what is coming, and they should have time to drive to Montgomery, email their senator. All of those things should take place.”