Alabama students saw record gains in the US on education test. Here’s why

Alabama made the biggest gains in the country in fourth grade math this year, new data shows, with scores reaching within one point of the national average.

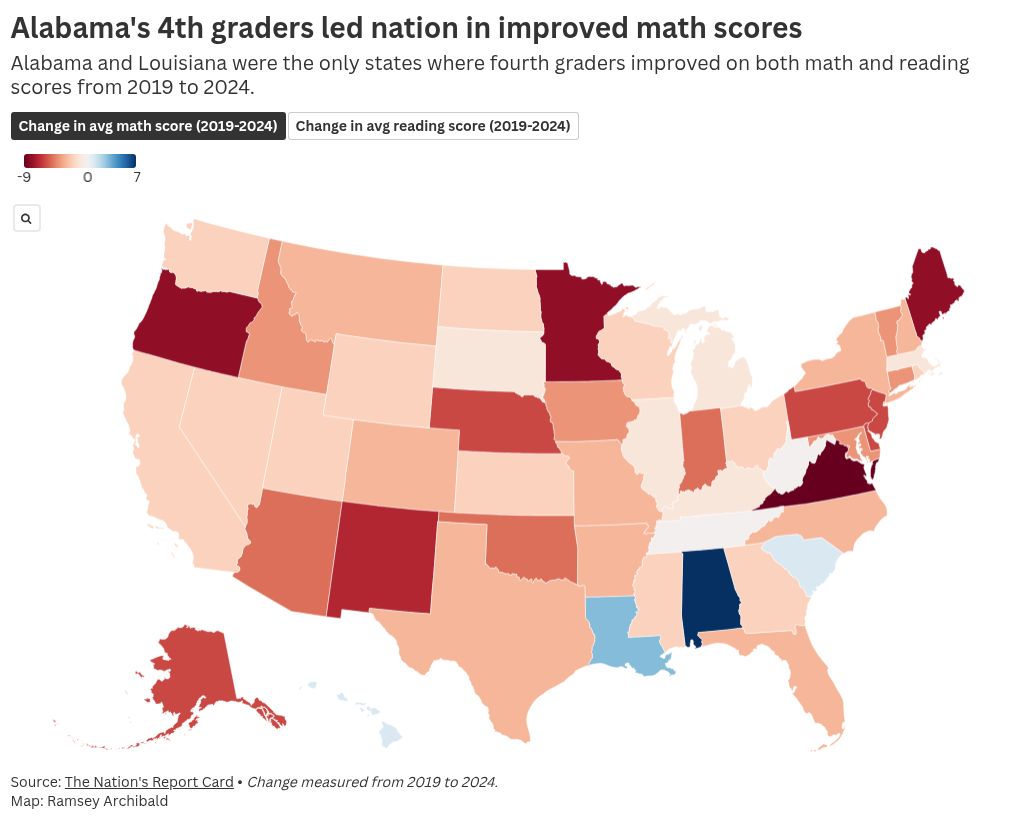

The state’s dramatic climb on the Nation’s Report Card – from dead-last in the nation to now 34th and 32nd in fourth grade reading and math – drew national attention this week. The simple reason: The state held steady, and improved in some places, while much of the country has yet to gain ground lost from the pandemic.

Across most of the country, American students are performing below their pre-pandemic counterparts, results show. So what makes Alabama different? Among some subjects and student groups, Alabama saw the highest growth in the country, and in the state’s history. (Can’t see the map below? View it here.)

“When we see these national headlines that say Alabama is bucking the trend and doing better, that’s good for our economy and that’s good for every Alabamian,” State Superintendent Eric Mackey told reporters Wednesday.

The National Assessment on Educational Progress is meant to measure a state or territory’s progress over time, but because the scores are estimates, researchers caution against using the test to rank or compare states against each other.

Over the last few years, Alabama has tweaked its own reading and math standards to more closely resemble the NAEP’s, which researchers acknowledge are some of the toughest standards in the nation.

AL.com took a closer look at how scores have changed nationwide since 2019, the last time students were tested before the pandemic.

The chart above measures states’ average scores, which represent students’ overall performance on each assessment. Average scores are different from achievement levels, which measure what kinds of skills students have mastered – and where they’re falling behind.

In fourth grade math, Alabama students earned an average score of 236 out of 500 – a jump of six points since 2022 and the highest the state has scored since the test began. Fourth grade reading held steady with an average score of 213, and eighth grade reading and math scores dipped by one and three points, respectively.

While early grade math was a clear standout, Mackey said he was surprised to see reading stay still, given previous dips in former third graders’ scores on the state’s reading test.

“I expected us to go backwards in reading by about four [points], based on what our state data shows,” he told board members this week. “So the fact that those students actually did not go back, it tells me two things. One, our state test is even more rigorous than I thought it was. And two is that our students, they’re holding their own, even in a difficult, difficult time.”

What does it mean to be ‘proficient’?

NAEP achievement levels are split into three different categories: basic, proficient and advanced.

The “basic” level more closely resembles most state standards and indicates partial mastery of fundamental skills.

In fourth grade reading, a student who scores at a basic level would be expected to sequence or categorize events from a text after reading a story. In eighth grade, students might be expected to draw the main idea from a story. “Proficiency” measures more sophisticated skills, like deciphering a non-fiction text or fact-checking an author’s claim.

In math, a big part of the test is assessing students’ “number sense”: Fourth graders are expected to understand decimals and have some basic understanding of fractions, while eighth graders should understand percentages and rates.

Nationwide, basic achievement levels in both subjects tanked, with more than 40% of fourth graders struggling to meet foundational reading and math standards. While high performing students seemed to be improving overall, many of the country’s lower performers scored at record low levels this year.

“Celebrating is not what I see in these data,” Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center on Education Statistics, told reporters this week. “Hope is what I see in these data, promise is what I see in these data, but I think we need to stay focused in order to right this ship.”

While Alabama celebrated its overall results, numbers show that many students still need to improve. And, like much of the country, gaps between students who are doing well and doing poorly on the test are widening.

In Alabama, 42% of fourth graders and 41% of eighth graders scored below basic levels in reading, while half of eighth graders scored below basic in math.

“It is still our struggling kids who are struggling, and our other kids are really accelerating,” Mackey said. “That means we’ve got to continue to focus on those students who need the extra help, extra resources.”

Alabama continues to stand out for its growth in fourth grade math proficiency, with about 37% of students scoring at or above proficiency this year, up from 28% in 2019 – the highest gain in the nation. (Can’t see the chart above? View it here.)

Less than a quarter, 24%, of students performed “below basic” in fourth grade math, compared to 29% in 2019.

In other subjects, Alabama students saw little to no growth in proficiency. In reading, 28% of fourth graders and 21% of eighth graders scored at or above proficiency levels. Just 18% of eighth graders were proficient in math.

Targeting those middle grades, Mackey said, will be a focus point moving forward. State leaders also plan to invest more heavily in programs outside of the classroom to help close gaps between high- and low- performing students.

“What we see is that nationally and in Alabama, during the pandemic and right after the pandemic, the families that had the resources, they hired extra tutors, they got extra support to build on what was going on in the classroom,” he added. “Families that either could not afford that or didn’t have the opportunity or resources for that continued to struggle to get the right after-school resources for their children. So you’re going to see us pushing over the next few years for historic investments beyond the classroom… whatever we need to do to support that extra work that will bolster what we’re already doing in the classrooms.”