Alabama-run NASA program finds first sign of giant black holes in dwarf galaxies on collision course

Astronomers with an Alabama-run NASA program have found the first evidence of giant black holes in dwarf galaxies on a collision course, which will help scientists understand galaxies and black holes in their infancy.

The findings were detected by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and published by University of Alabama students and a UA professor in The Astrophysical Journal.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville manages the Chandra program, while Chandra’s science and flight operations are conducted in Massachusetts.

Collisions between the pairs of dwarf galaxies identified in a new study have pulled gas towards the giant black holes they each contain, causing the black holes to grow. Eventually the likely collision of the black holes will cause them to merge into much larger black holes. The pairs of galaxies will also merge into one.

Scientists think the universe was filled with small galaxies, known as “dwarf galaxies,” several hundred million years after the Big Bang. Most combined with others in the crowded, smaller volume of the early universe, setting in motion the building of larger and larger galaxies now seen around the nearby universe.

Dwarf galaxies contain stars with a total mass less than about 3 billion times that of the sun, compared to a total mass of about 60 billion suns estimated for the Milky Way.

“Astronomers have found many examples of black holes on collision courses in large galaxies that are relatively close by,” said University of Alabama graduate physics student Marko Micic, who led the study. “But searches for them in dwarf galaxies are much more challenging and until now had failed.”

The earliest dwarf galaxies are impossible to observe with current technology because they are extraordinarily faint at their large distances. Astronomers have been able to observe two in the process of merging at much closer distances to Earth, but without signs of black holes in both galaxies.

The new study overcame these challenges by implementing a systematic survey of deep Chandra X-ray observations and comparing them with infrared data from NASA’s Wide Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and optical data from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT).

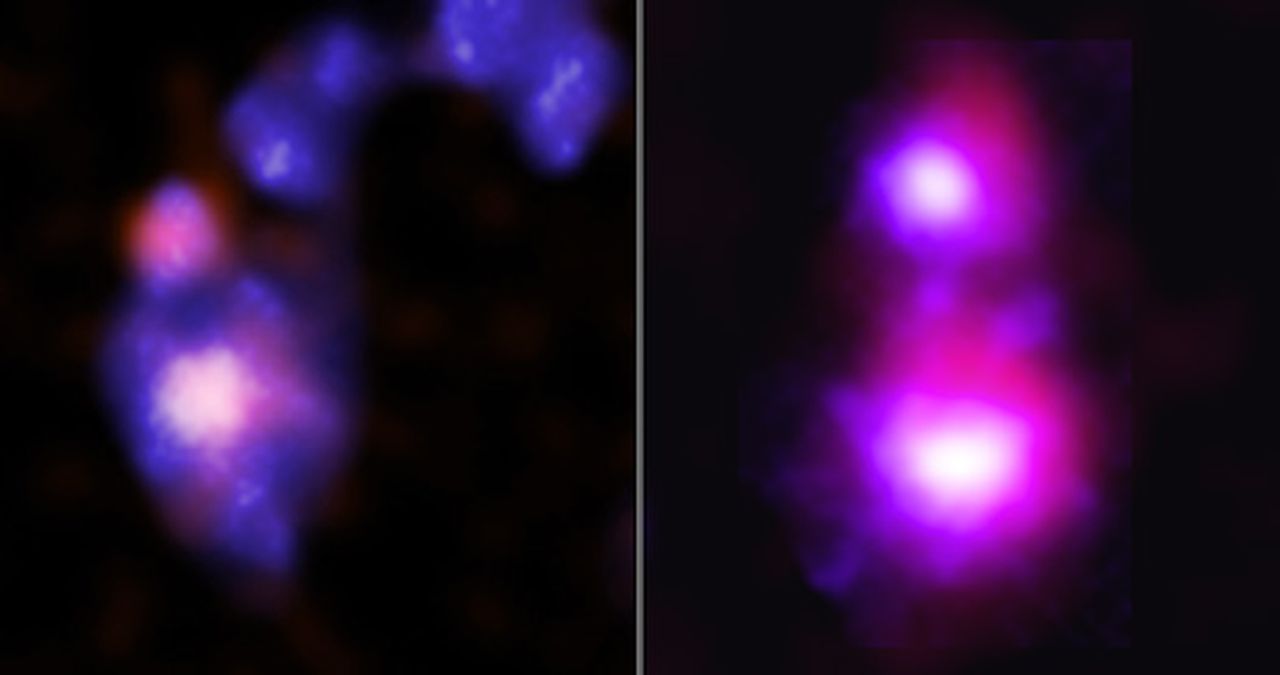

Chandra was particularly valuable for this study because material surrounding black holes can be heated up to millions of degrees, producing large amounts of X-rays. The team searched for pairs of bright X-ray sources in colliding dwarf galaxies as evidence of two black holes, and discovered two examples.

“We’ve identified the first two different pairs of black holes in colliding dwarf galaxies,” said UA physics student and co-author Olivia Holmes. “Using these systems as analogs for ones in the early universe, we can drill down into questions about the first galaxies, their black holes, and star formation the collisions caused.”

One pair is in the galaxy cluster Abell 133 located 760 million light-years from Earth. The other is in the Abell 1758S galaxy cluster, about 3.2 billion light-years away. Both pairs show structures that are characteristic signs of galaxy collisions.

The pair in Abell 133 appears to be in the late stages of a merger between the two dwarf galaxies, and shows a long tail caused by tidal effects from the collision. The authors of the new study have nicknamed it ‘Mirabilis’ after an endangered species of hummingbird known for their exceptionally long tails. Only one name was chosen because the merger of two galaxies into one is almost complete.

In Abell 1758S, the researchers nicknamed the merging dwarf galaxies “Elstir” and “Vinteuil,” after fictional artists from Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time.”

The researchers think these two have been caught in the early stages of a merger, causing a bridge of stars and gas to connect the two colliding galaxies.

The details of merging black holes and dwarf galaxies may provide insight to our Milky Way’s own past, researchers said. Scientists think nearly all galaxies began as dwarf or other types of small galaxies and grew over billions of years through mergers.

“Most of the dwarf galaxies and black holes in the early universe are likely to have grown much larger by now, thanks to repeated mergers,” said UA physics and math student and co-author Brenna Wells. “In some ways, dwarf galaxies are our galactic ancestors, which have evolved over billions of years to produce large galaxies like our own Milky Way.”

“Follow-up observations of these two systems will allow us to study processes that are crucial for understanding galaxies and their black holes as infants,” said UA professor and co-author Jimmy Irwin.