Alabama lawmakers still pursuing transportation commission 35 years after weekend filibuster

A majority of Alabama will celebrate Easter this weekend. The future of the state transportation department will not be on anyone’s mind.

But exactly 35 years ago, the Alabama State Senate was embroiled in a rare weekend filibuster over the future of leadership within the State Department of Transportation.

The legislative push-and-pull over April 9-10, 1988, involved taking the state’s Highway Department away from then-Gov. Guy Hunt’s oversight. Change did not happen, but backroom deals were cut in which one lawmaker later lamented, “I got the shaft.”

Fast forward to the Legislature’s 2023 session, and a bill has once again surfaced to reform the Alabama Department of Transportation. It’s chances of passage are remote, but that’s not stopping the bill’s latest sponsor to file it in hopes it will rattle a shakeup in how ALDOT is operated.

“I am trying to start a conversation,” said state Rep. Chris Pringle, R-Mobile, the House Speaker Pro Tem, who is sponsoring HB83, which establishes a five-member State Transportation Commission that will replace the director of the Alabama Department of Transportation.

Lack of planning

Commissioners would be appointed by the governor and would serve staggered six-year terms. They would also select ALDOT’s director, a position that would no longer be selected directly by the governor’s office.

If it were approved, Alabama would join a number of states with transportation commissions that are responsible for the programming and allocation of public funds for roadwork. Among them are Mississippi, Texas, California, Michigan, Missouri, Colorado, and Washington.

“I want people to know the problem we have in the state of Alabama is a lack of transportation corridors being built,” Pringle said about why he believes the timing is right to have the issue reconsidered during this spring’s session. “Right now, there is no long-term planning.”

He said he wants to see the change happen to “bring some continuity and long-term planning and completion” of road projects within his district and beyond.

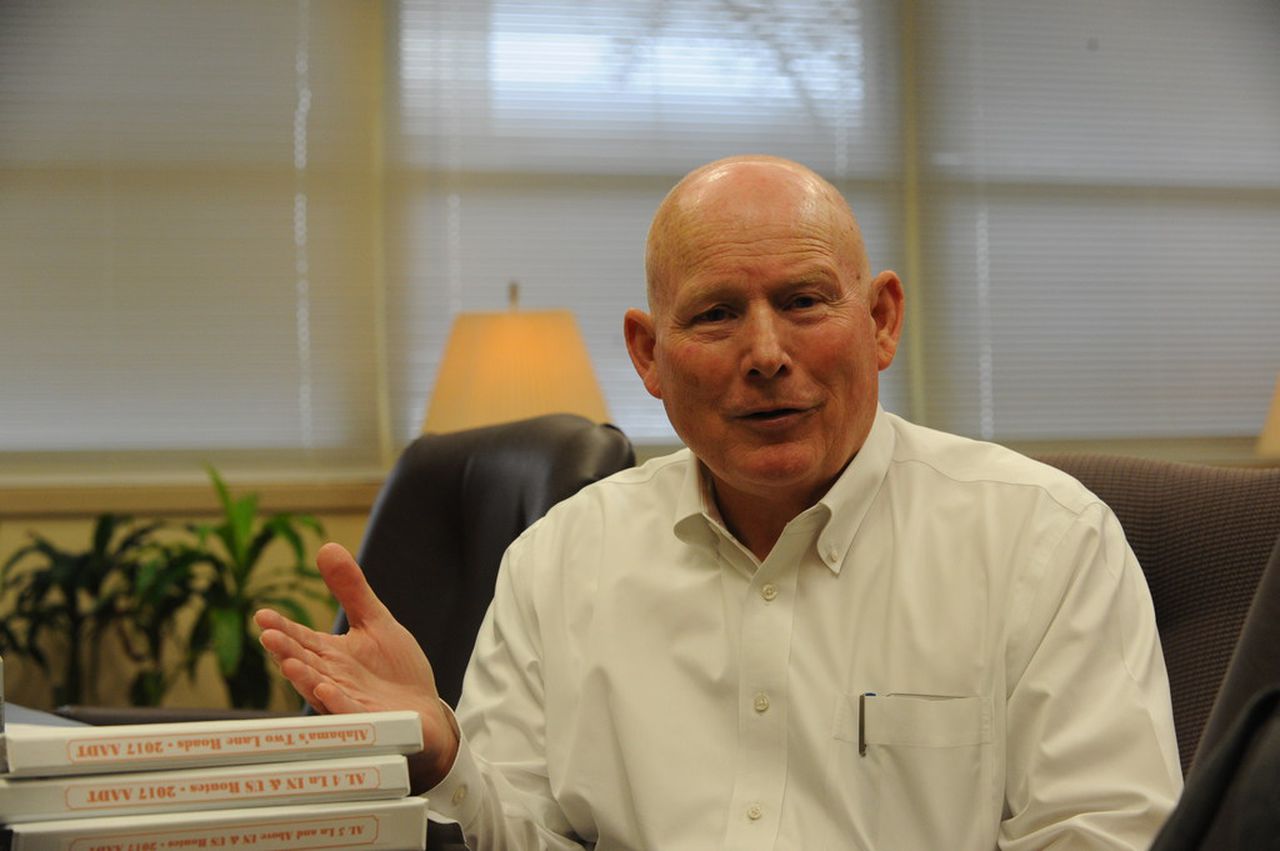

Alabama Department of Transportation Director John Cooper speaks on Wednesday, December 19, 2018, inside his office in Montgomery, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Tony Harris, spokesman with ALDOT, said the agency is operating under the “longest period of continuity and long-range planning in its history.” Cooper, who became ALDOT director in January 2011, is the department’s longest serving director since it was founded in 1911. Joe McInnes, who was director before Cooper, served from 2003-2011.

“That’s one of the main reasons why the state has been able to make unprecedented investments in Alabama’s long-term transportation needs,” Harris said. “Every region – in fact, every county – is seeing important road and bridge improvements that are local priorities.”

Frustrated lawmaker

Similar bills have been introduced in Alabama for decades and had some momentum with support by former Governors Don Siegelman and Bob Riley. Despite support from the governors, the bills never advanced far.

In fact, there have been only eight legislative sessions since 1998, that a commission legislation was not filed.

Pringle’s proposal is a longshot to advance out of the Alabama House, let alone make it to the governor’s desk. The governor’s office, as they do with other bills, told AL.com they will continue monitoring it as it moves through the legislative process, but declined further comment.

The legislation could allow some lawmakers to vent frustrations over road projects they want to see advanced.

Pringle, like other lawmakers in Mobile County, said he is frustrated with the lack of movement on adding two lanes for approximately 60 miles of U.S. 45 in South Alabama. A new four-lane road would connect with the four-lanes of U.S. 45 that exists in Mississippi toward Meridian, and north into the Midwest until terminating in Michigan.

ALDOT has estimated the road widening at more than $300 million, and the state has not viewed the roadway as a priority for widening compared to other two-lane highways in the state.

“U.S. 45 has been a part of the highway plan for 40 years,” said Pringle. “How can you put a road in a five-year plan and 40 years later, you haven’t touched it?”

Pringle also said he is frustrated in communications with Cooper, citing an incident in 2018 in which he claimed the ALDOT director told him it would be a “total waste of my time” to meet with newly elected legislators to review the state’s long-term transportation plans.

Pringle said that Cooper claimed there would be no “long-term plan” until Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey was elected that year.

Transportation planning

Visitors to the Mobile Metropolitan Planning Organization’s hearing into the I-10 Mobile River Bridge and Bayway project look over the plans for the $2.7 billion project. The meeting was held on Wednesday, June 29, 2022, at the Alabama Department of Transportation’s training room in Mobile, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

ALDOT has traditionally relied upon Metropolitan Planning Organizations for establishing short- and long-term planning documents to guide ALDOT’s transportation priorities.

Those documents are often referred to as Transportation Improvement Plans and have offered crucial directions for ALDOT as the state pursues federal transportation financing to build major roadways.

There are 14 MPOs that hold influence over transportation planning in Alabama, including Mobile. Those organizations provide a list of projects that make up 70-75 percent of Alabama’s State Transportation Improvement Plan (STIP), which includes projects listed within the MPO’s TIPs. ALDOT is also responsible for planning outside the MPO areas, which includes rural counties throughout Alabama.

Transportation plans cover four fiscal years, and the process to prepare the next long-range transportation plan is underway. ALDOT is beginning this month to gather public comments about the fiscal year 2024-2027 STIP. The state’s fiscal year begins October 1.

“By law, ALDOT operates under a long-range transportation plan and coordinates with local governments to include their priorities,” Harris said. “We will continue to work with local leaders on their priorities, including the many projects currently ongoing in the Mobile area such as the U.S. 98/State Route 158 corridor, the widening of I-10 in Mobile and the Mobile River Bridge and Bayway project.”

Pringle also criticized the state for a lack of what he said are transportation corridors, including an existence of counties untouched by the interstate system.

ALDOT has an economic development program in place that includes projects like the widening of U.S. 411 from Cherokee County to Gadsden, and the Highway 52 corridor through southeast Alabama including Dothan.

The $115 million widening of U.S. 411 from Gadsden and Leesburg, and the addition of a connector of Interstate 759 and U.S. 431 in Gadsden, were the first Rebuild Alabama Act projects within the program’s economic development category. Rebuild Alabama was approved by state lawmakers in 2019 and is funded through a 10-cent-per-gallon increase in the state’s fuel tax.

That project, when completed, will remove Cherokee County from the list of 17 Alabama counties lacking interstate connectivity.

Alabama is slowly improving in the grades it receives from the American Society of Civil Engineers. Though the state’s overall infrastructure grade of a C- remains unchanged from 2015, Alabama has seen slight improvements in roads (C- in 2022, compared to D+ in 2015), and bridges (C+ in 2022, C- in 2015). The report praises the Rebuild Alabama Act, coupled with the federal bipartisan transportation plan, for placing Alabama’s infrastructure on the “cusp of transition.”

Political maneuvering

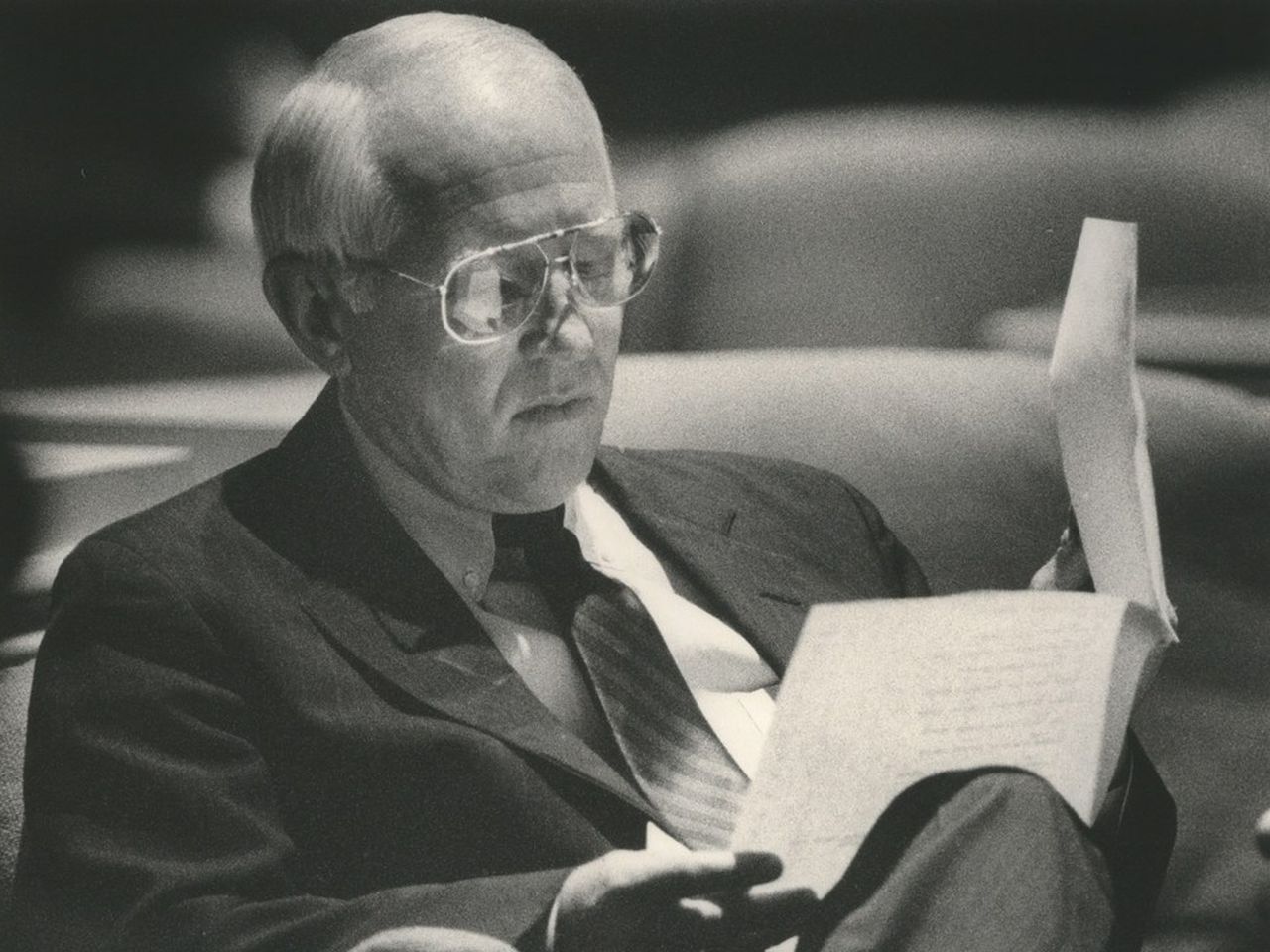

Alabama State Senator Crum Foshee at desk on Senate floor in this picture dated in 1990. (file)

Phillip Rawls, a former Auburn University journalism professor and retired journalist who covered Alabama state politics for The Associated Press, said that bills setting up a transportation commission used to be introduced by lawmakers because of a belief they would be less political than “letting a governor oversee road projects.”

During Gov. George Wallace’s tenure, road projects were used as a political cudgel to gain crucial votes for one of the governor’s priorities.

But there were times when lawmakers utilized reforming the transportation agency to their advantage.

Following the 1988 filibuster, then-Senator Crum Foshee, D-Andalusia, was able to secure funding to straighten Alabama State Route 55 between Andalusia and I-65 in Georgiana.

At the time, Hunt wasn’t interested in the project, Rawls recalled. But the highway commission bill, which Foshee did not sponsor, did get the governor’s attention sparking plenty of backroom politicking.

The timing of the road project coincided with an expansion of Shaw Floors in Andalusia, which was seeking a better route for its trucks to get from the city to I-65. And the project proved beneficial for beach-bound motorists as the four-lane Route 55 serves as a thoroughfare to Fort Walton-Destin.

“Foshee secured lots of good jobs for Andalusia at a time when many small Alabama towns were hurting from a decline of the textile industry,” Rawls said. “It’s no surprise the Legislature, subsequently, named Alabama 55 in Foshee’s honor.”