Alabama lawmakers fret over potential of returning $100 million or more in COVID funds

Alabama lawmakers are worried over the prospects of returning more than $100 million in federal American Rescue Plan Act money if it’s not spent soon.

Their concerns are so much so that they are planning to increase meetings with heads of several state agencies charged with administering the federal money allocated to states following the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We are trying to make sure we get this money into Alabama ground as much and as soon as possible,” said Senator Greg Albritton, R-Atmore, who chairs a legislative oversight committee that could be meeting monthly to review how the money is spent.

“I don’t believe there will be an extension of time (by the federal government), and if anything, my worry is that it could be shortened,” Albritton said. “It is better to be safe than sorry.”

At issue is whether more than $900 million in money allocated for water and sewer and broadband projects can be spent before a December 2026 deadline imposed by the U.S. Treasury Department on ARPA funds.

Atop the list of concern that of approximately 390 water and sewer projects overseen by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management, only 79 have returned signed agreements indicating the projects can move forward.

Of those 79, a significant number are not even under construction yet.

“That’s really concerning,” said state Senator Chris Elliott, R-Josephine.

He along with some other state lawmakers are pushing to have some of the unspent money reallocated to other projects within their districts.

In Elliott’s case, that includes utilizing unspent ARPA funds on shovel-ready projects within his district. One example would be for the support of an $11 million water line extension south of Fairhope into a rural area of Baldwin County where there is a lack of available drinking water.

“Fairhope is scrambling to fix their problems with very limited resources,” Elliott said, referring to multiple water emergencies declared by city officials and the implementation of water restrictions within the city this summer.

Other lawmakers said that rural utilities in poorer areas of the state are unable to pay back a state loan that would be provided to them to finish out their infrastructure projects.

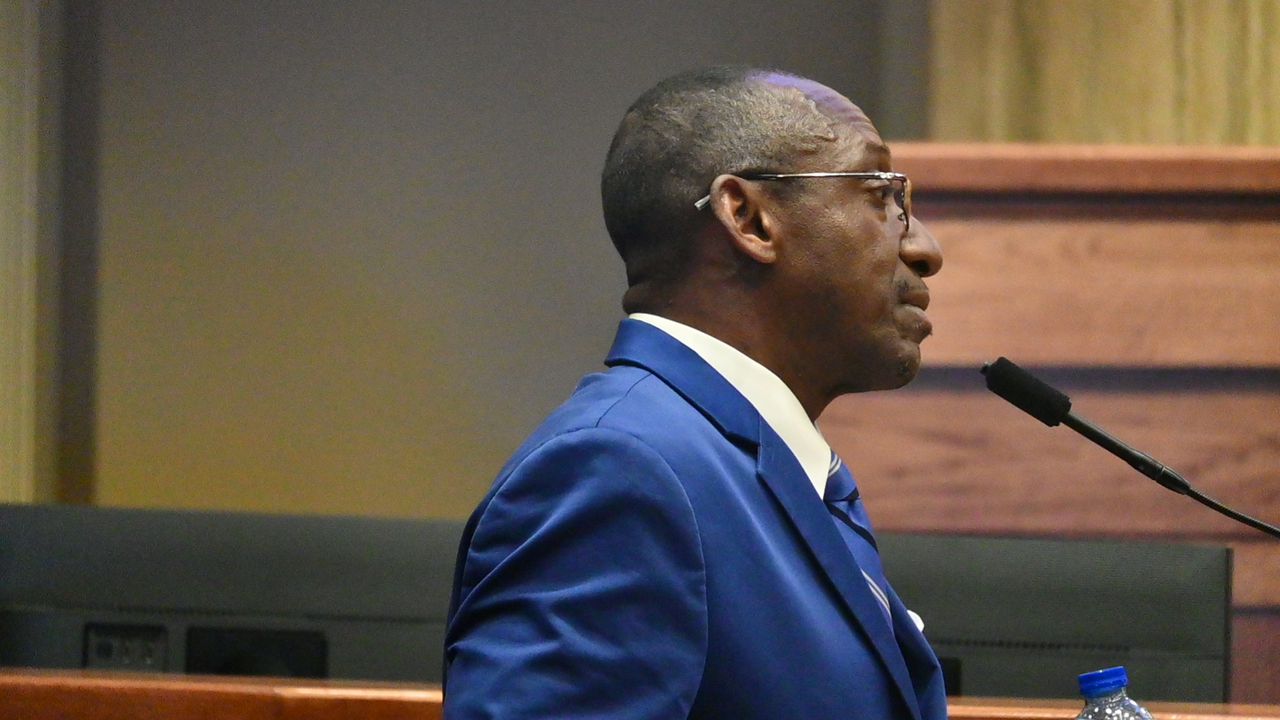

Alabama State Senator Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro, speaks on the floor of the Alabama State Senate on Thursday, June 2, 2023, at the State House in Montgomery, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

“I’m getting calls from communities, and they are feeling that they are being told you either take the money or you don’t get anything at all,” said state Senator Bobby Singleton, D-Greensboro, during a recent oversight committee meeting. He did not single out a city that was faced with a concern of having to repay revolving loan funds with limited resources.

“A loan will put them into more debt and they (are being told) to take it or leave,” said Singleton. “I hope that is not the message to the communities when we should be helping them with their problems instead of forcing something n them that they cannot afford.”

ADEM Director Lance LeFleur told Singleton that his agency, when assessing a project proposal, will look at an utilities or a local government agency’s financial capabilities to undertake a local match requirement.

A spokeswoman with ADEM, in an email last month to AL.com, said that project awards are determine only where appropriate engineering and financial packages have been thoroughly analyzed and structured for successful implementation.

Lynn Battle, chief of the Office of External Affairs with ADEM, said that all awards from ARPA and other funding sources include a notification to the recipient about deadlines that must be met, and a required written contract obligation to meet the deadline.

Failure to meet milestones toward the deadlines will subject the recipient to a withdrawal of the commitment of funding and the fund will be reallocated to projects that can complete construction within the allowable timeframes,” Battle said.

She said ADEM has long said it would be prioritizing funding on “a needs basis where it is unlikely the project would be implemented without state-funded assistance.”

She added, “ADEM has a procedure in place to assure that no funds will be returned to the federal government.”

Elliott has expressed concerns about how ADEM is ranking projects for ARPA funding, saying that high-growth areas like Baldwin County are not given enough consideration.

LeFleur has said the agency prioritizes projects for grant money where the needs are the greatest when it comes to financial assistance and physical plant or infrastructure issues. High-growth areas are not considered areas of the most need.

Fairhope Mayor Sherry Sullivan speaks during a 9-11 ceremony on Friday, September 10, 2021, in downtown Fairhope, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

Fairhope Mayor Sherry Sullivan said her city has applied for ARPA money on projects that are underway. Included in that is a $6.4 million water line project at Fairhope Avenue and Baldwin County Road 33, which is underway. She said the city is willing to provide a local match on that project.

“We are a high growth area, and we are playing catch up, to be quite honest,” Sullivan said. “When (ADEM) is looking at underserved areas, yes they are in need. But this is unprecedented growth we are seeing in Baldwin County and I don’t know of anyone that would been prepared (for it).”

Related: Fast-growing Fairhope invests millions to keep up with water demand

Albritton said the struggles to get projects moving forward are not just with rural utilities in small areas, including the Black Belt region where a lack of running water and sanitary sewer systems has plagued the region for generations.

That issue is generating national attention, and federal court interest. A first-ever civil rights settlement between federal authorities and the state over environmental justice occurred earlier this year over a lack of progress with ensuring residents in Lowndes County were receiving adequate water and sanitary sewer services.

“Giving back federal money would be a sin,” said Albritton, and then he mentioned how there are utility needs in Mobile, Birmingham, and beyond.

“I’m concerned that people see the dollars more than they see the responsibilities (of administering each project),” Albritton said. “By December 2026, that money needs to be spent. That means with those projects … the last dollars need to be out the door, and if it’s not out the door by 2026, there is the opportunity for clawback.”