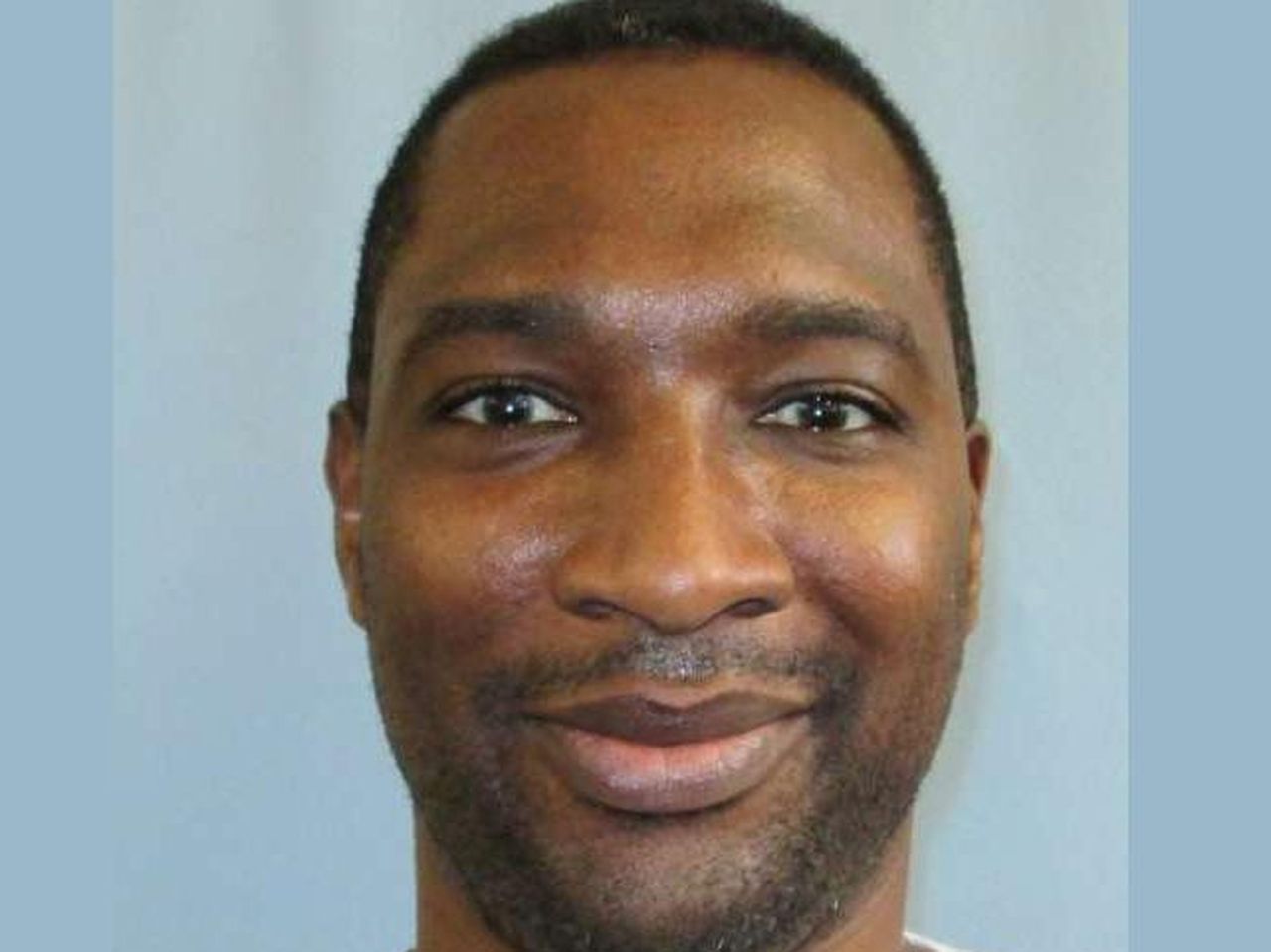

Alabama Death Row inmate, convicted of burning man alive, seeks new sentence

Attorneys for an Alabama Death Row inmate told a federal appeals court on Wednesday that Robert Shawn Ingram was so likely to be convicted and sentenced to death during his 1994 trial that an effective attorney would have encouraged a plea deal to spare his life.

But the Alabama Attorney General’s Office argued Ingram knew the risks of not going through with his negotiated plea and made the decision on his own after consulting with his trial lawyers and after a judge informed him of his rights.

Attorneys for Ingram and the state argued on Wednesday morning before a three-judge panel of U.S. Eleventh Circuit Court judges at the appeals courthouse in Atlanta.

Circuit Court Judges Adalberto Jordan, Britt Grant, and Elizabeth Branch heard the arguments. Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall was not present for the hearing.

Ingram was convicted in Talladega County for the July 1993 kidnapping and burning death of Gregory Huguley a year prior. Huguley was abducted at gunpoint by Ingram and several other men, according to court records, from a street in Anniston after failing to pay a drug debt. He was taken to a park, taped to a bench, and doused with gasoline before the men set him on fire.

In his latest appeal, Ingram’s lawyers from the Federal Defenders for the Middle District of Alabama argued that Ingram negotiated a plea agreement to a parole-eligible sentence on his own after police arrested him in 1993, with the agreement he would testify against his co-defendants. But when it came time to testify, he didn’t take the stand.

Prosecutors withdrew their plea agreement, and Ingram went to trial. There, he was convicted and sentenced to death.

Lucie Butner, Ingram’s lawyer, told the judges Wednesday that despite Ingram’s sudden decision to not go through with his plea deal 30 years ago, his trial lawyer “did almost nothing” to warn him of the likely outcome of a trial. She said that during a previous hearing, the trial lawyer testified he had “no doubt” Ingram would be convicted of capital murder if put before a jury.

Under questioning from the appeals court judges as to what the initial lawyer should have done, Butner said there was a “fundamental obligation” of the lawyer to understand why Ingram changed his mind.

And if he would have investigated that reasoning, she said, the lawyer would have learned what Ingram told a judge in another appeals hearing: That he was under the impression—after consulting with his co-defendants in the county jail—that if no one testified against each other, they would all be released.

“If no one talks, everybody walks,” Butner described Ingram’s mindset.

She told the judges Wednesday that, although the trial judge informed Ingram of his legal rights and what he could do regarding a plea or trial, it was his lawyer’s job to advise him of specific concerns and his likely outcome. It was the responsibility of a “reasonable trial attorney who knows he will be convicted,” to talk to him, Butner argued.

“He did the bare minimum, if that.”

Deputy Solicitor General Barrett Bowdre argued for the state Wednesday morning. He said that Ingram’s trial lawyer told him the risks of backing out of his plea agreement and advised him to keep it.

He said that there is no proof Ingram could have been swayed to change his mind, no matter if the lawyer had pushed him or contacted his family members to try and convince Ingram. He noted that the trial lawyer previously testified Ingram was “adamant” on his decision.

“During (a meeting with his attorneys and the trial judge), the State noted that Ingram had given a statement admitting his involvement in the crime, that it was viewing his failure to testify against (a co-defendant) as a breach of the plea agreement, that it would try Ingram for capital murder, and that it intended to use Ingram’s statement against him at trial,” said the AG’s office in a brief filed to the appeals court.

“Mr. Ingram did not understand the consequences of rejecting the plea deal he was offered in exchange for his testimony,” his lawyers argued in a brief to the appeals court. “Mr. Ingram’s trial counsel was ineffective and did not provide competent advice…”

In a lower court hearing, Ingram testified that he would have accepted the deal and testified if he understood that his deal would spare his life. He said he didn’t know he was basically certain to be convicted, given his admission to police and eyewitness statements, and sent to death row. If his lawyers would have explained that, Ingram testified, he would have stuck with the plea deal.

Ingram said he believed just admitting his role in the brutal killing would be beneficial for him. “I thought I had helped the police so much, I actually thought I was going to be okay from day one,” he told a lower court.

“Because of counsel’s failure to provide competent advice that Mr. Ingram could understand, his conviction for capital murder and his sentence of death were more serious than the outcome would have been had he not rejected the plea,” his lawyers argued in a filing.

Ingram’s lawyers are asking the court to send the case back to Talladega County, throw out his conviction and death sentence, and resentence Ingram to what he would have received under the initial plea agreement.

“Mr. Ingram’s claim is straightforward: had he received competent advice and been counseled so he could understand, he would have accepted the terms of the plea and testified against Mr. Boyd,” his team said.

“What counsel did was not enough,” Butner said Wednesday. “Counsel did not ask (why he changed his mind… and counsel had a duty to ask.”

“He did not tell his client that he would not walk.”