After clearing council hurdle, Mobile’s push to be second-largest in Alabama awaits the voters

After the Mobile City Council voted Tuesday to allow for a special election on annexation, Freddy Wheeler took to Facebook and quoted Gene Stallings.

“In 1992, after defeating the University of Florida in the first-ever SEC Championship game, Alabama (head coach) Gene Stallings told everyone ‘we haven’t done anything but win another game,’” Wheeler wrote on the West Mobile Annexation Committee’s page.

“We have finally achieved reaching the goal line,” he added. “The question remains, can we score the game winning touchdown or will we let apathy defeat us?”

Indeed, the major political hurdle for pro-annexation advocates in Mobile is behind them with the council’s unanimous vote on Tuesday.

But a rare special election looms that carries high stakes with the results possibly propelling Mobile’s population to well over 200,000 residents. If all four unincorporated areas west of Mobile vote to support annexation, the city will leapfrog Montgomery and Birmingham to become the second-largest city in Alabama trailing only fast-growing Huntsville.

Related content:

Plenty of logistical questions remain including when the actual election will take place.

Mobile County Probate Judge Don Davis, in an email to AL.com, said “there is a lot to be done to prepare for this election,” noting difficulties that await in recruiting poll workers and determining how many polling places will be set up for the special election.

Davis is expected to meet soon with Mobile Mayor Sandy Stimpson’s administration, who will officially hand over the council’s request for the special election.

James Barber, chief of staff to Stimpson, said on Tuesday that once Davis receives the resolution, he has 10 days to call for an election. And then that election has to occur “no less than 20 days and no more than 40 days” from that point.

Logistical issues

Obstacles include scheduling the special election a time for summer vacations, holidays, and the July 25 special election to fill the vacant Mobile City Council District 6 seat. That seat was vacated by Scott Jones, who resigned from office last month.

The Mobile City Clerk’s Office is handling the District 6 election, while Davis’ elections office is charged with administering the annexation vote.

Barber said his office spoke with Davis about lumping those two elections together. The two, Barber said, decided “it would not be wise.”

“It would be confusing to people, even though it’s different voting blocs,” Barber said.

Davis said there are holidays that must be considered before setting the special election date – Memorial Day, Juneteenth and Independence Day. He also said July 25 special election is also an issue that must be considered.

Mobile taxpayers will foot the bill for the special election, though Davis had no estimate on the expenses yet.

He said several issues will determine the costs, including whether the city will issue post cards, rental fees for poll locations, poll worker compensation, and whether the city chooses to use the probate office’s electronic poll note book system.

“These are the key things that will impact the expense of the election,” said Davis. “We will meet with city officials to see how they want to approach the election.”

Davis said poll locations and poll worker training sites need to be secured, and “we must identify, recruit and train the poll workers.”

He added, “Since this is a geographically based election that doesn’t exactly ‘fit’ our existing election precinct mapping system, identifying poll workers is going to be more challenging than usual.”

Campaigning

Davis said he is encouraging Mobile city officials to send a post card to every citizen in the affected areas to provide key election-related information. Mobile is not legally required to do so, he said.

“It takes time to formulate such cards, prepare them and get them issued with meaningful time for citizens to act upon the information contained (in the cards),” Davis said.

Information released from Government Plaza, contained on an official city document, cannot be construed as being campaign-related.

“The City of Mobile can share information and answer questions that county residents may have about joining the city but can’t use public funds to promote a specific vote in the referendum,” said Jason Johnson, a city spokesman.

He said the information released from Government Plaza will include how joining the city will impact residents in the areas participating in the referendum, “following all applicable campaign and election guidelines.”

“Mayor Stimpson and the administration have all navigated political campaigns while holding public office before,” Johnson said.

He also said that residents will see pro-annexation activity occur from “privately funded, pro-annexation political action committees” separate from the City of Mobile.

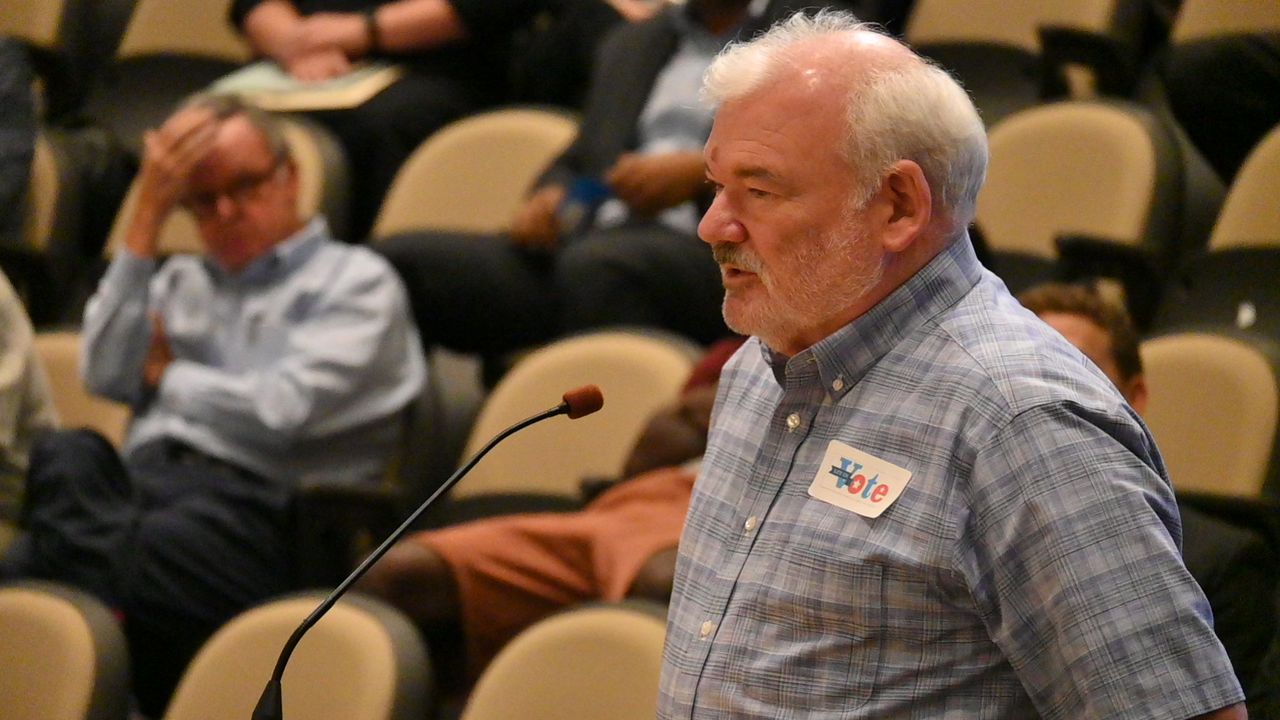

Del Sawyer, president of the West Mobile Annexation Committee, speaks out in support of an annexation proposal during the Mobile City Council meeting on Tuesday, May 9, 2023, at Government Plaza in Mobile, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

The West Mobile Annexation Committee will also be campaigning in support of annexation.

“We’ve got a team that will be meeting soon and putting together a boots on the ground effort in the areas to education and inform and gain support,” said Del Sawyer, who has headed up the committee since the last time a major annexation plan surfaced, but did not make it out for consideration

Expectations are that anti-annexation voices will continue, including those from the group Stand Up Mobile, which circulated campaign-style flyers opposing plans to add more residents throughout inner city neighborhoods. Their concerns are that adding a large number of residents will dilute city services in long-established neighborhoods.

Outside groups will also be keeping an eye on the results. The Southern Poverty Law Center, in 2021, wrote to the Stimpson administration warning them about the potential of violating Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act if annexation undermined Mobile residents’ right to “fair and equitable representation the City Council.”

That letter was issued before the council, last August, voted to support a new redistricting map that – for the first time in the city’s history – included four majority Black council districts. The council’s racial makeup has long been four white members, three Black.

Shalela Dowdy, a law student and plaintiff in Milligan v. Merrill, the voting rights case currently under consideration by the U.S. Supreme Court,” expressed concerns about diluting Black representation ahead of the council’s vote, saying that “voter suppression continues, but in disguise through the rose-colored glasses of annexation.”

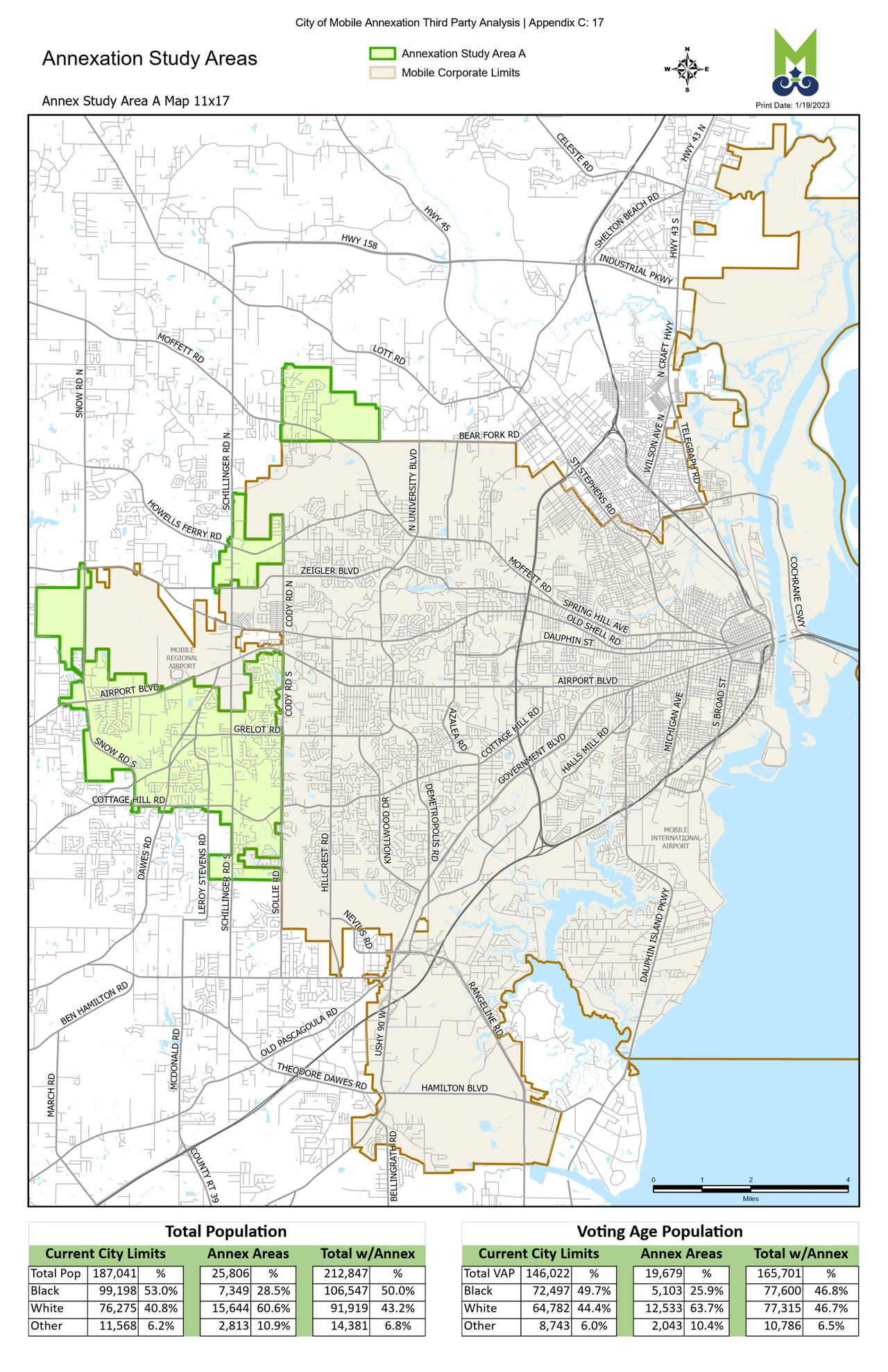

The annexation proposal would bring in larger swaths of white voters to Mobile, but it also maintains a slight Black voting-age majority only if all areas targeted for annexation vote to support it.

Sawyer said he is confident in the heavily populated Cottage Hill region supporting annexation. Combining that area with neighborhoods near Mobile Regional Airport, a total voting age population of 17,254 residents would be added. The demographics of that area are 63.4% white, 22.4% Black.

Two smaller areas – King’s Branch and Peachtree – are majority Black areas. It’s unclear how those two areas will vote, and Sawyer admits that his committee has work to do to convince them on the advantages of being annexed into Mobile.

“The focus has not been heavy in those areas,” said Sawyer. “We feel an obligation to bring them on board and d what we need to do to educate them. It would be a shame, after the fact, for these other neighborhoods to be on the outside looking in.”

Growth potential

Annexation Study Area A. This proposal would annex 25,806 residents into the city of Mobile. The city council will vote on four resolutions Tuesday to authorize a referendum in this area on whether or not the residents want to be annexed. (Graphic courtesy City of Mobile)

If all areas targeted for annexation vote to be incorporated, Mobile’s population will increase by 13.8% from 187,041 residents (according to the 2020 U.S. Census) to close to 213,000 residents. Huntsville will remain Alabama’s largest city at 215,006.

The 2021 U.S. Census population estimate for Mobile was at 186,833.

Mobile’s population projections, without annexation, are expected to continue a decline. An estimate puts that population dip to 179,305 by 2030, which is likely to keep the city at the fourth-largest in Alabama and still well-ahead of the state’s fifth-largest city, Tuscaloosa, which is at slightly more than 101,000 residents.

Montgomery and Birmingham are also shrinking in population. Montgomery is the state’s second-large city at 198,665, according to 2021 U.S. Census estimates. Birmingham is at 197,575, according to the estimate.

Stimpson, following the council vote, said the advantages of boosting Mobile’s population above 200,000 means it’s more eligible for federal grants to help provide additional resources for its police and fire departments.

“If we are successful and all (25,806) come in, then we will be the second largest city in the state of Alabama,” Stimpson said. “It’s exciting. It’s a major milestone.”