A Birmingham church bombing murdered their daughter, but it didnât steal their joy

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was an act of racial terrorism, but it didn’t erode the warmth of the McNair family.

Evidence of this can be found in the living room of the McNair home in Birmingham, Ala. The architecture of the space evokes the feeling of a church celebrating Black life with its high, vaulted ceilings, wooden beams and collection of family photographs adorning the walls and tables. Above a piano is a large picture of Chris McNair and his wife, Maxine, smiling on their wedding day in 1950. Nearby, there’s a wide shot of Maxine singing in the choir during the 50th class reunion at their alma mater Tuskegee University. Across the room, there’s a picture of Chris’ mother and father sharing a drink during their 50th wedding anniversary.

Beaming throughout the collection is the smile of Denise McNair, Chris and Maxine’s first born child who was killed during the church bombing on Sept. 15, 1963. At 11 years old, Denise was the youngest victim of a bombing that also murdered 14-year-olds Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins and Carole Robertson.

Denise’s death left a heavy absence in the couple’s lives, and they knew racial oppression would be a constant presence in the world. But as people of faith, they didn’t allow that reality to consume their wellbeing. They added more richness to their life by expanding their family. Lisa McNair was born almost a year after the bombing. About four years later, the McNairs welcomed a new bundle of joy, Kimberly McNair Brock. Chris, a professional photographer, snapped a picture of a young Lisa smiling at her new sibling the day Maxine brought Kimberly home.

“They were black people in America, and they knew that sometimes this stuff just goes on for a while, but there’s not anything you can do about it,” Lisa said. “So you need to turn it over to the Lord, decide you’re going to move forward, and then the joys that are in life that come to you, you take them. You make the best of those wonderful opportunities.”

Death didn’t stop Lisa from bonding with her older sister. She pieced together Denise’s personality in clever ways. Some of it was through family stories that illustrated Denise’s silly personality. Most of it was through the photos of Denise taking her first steps, petting the family dogs, hugging a baby doll or posing next to her cousin, Lynn – a family member Denise was close to in age and spirit.

Denise McNair, one of the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing poses in the front yard with her dog Whitey in 1962 in Birmingham, Alabama. (Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

Denise’s jolly attitude speaks to her jovial and serene upbringing. Lisa described her father as a man who would liven the environment with laughter. He was a jokester who would make funny nicknames for his daughters and would do a funky little dance sometimes when he heard music.

“You know how parents think they are cool, but they’re not,” Lisa laughed. “It was just small things like that.”

Maxine was known as a dedicated educator who positively influenced her students during her 33-year tenure with Birmingham City Schools. It would be 30 years before Klu Klux Klan members were convicted of the bombing, but Lisa said her mother carried a calm spirit.

“My mother was a very happy person,” Lisa said. “She just knew how to have peace – peace of God and joy.”

She also was known for her very powerful singing voice. Dale Long, a friend of the family who was the same age as Denise when he stumbled out the wreckage of the bombing, remembers being awed by Maxine’s singing voice.

“She had a voice that you wouldn’t believe,” Long said. “I mean, she would sing like a bird in the choir. I was just overwhelmed even as a child. When the choir was doing something and she was the soloist – I mean, just unbelievable.”

Bombing victim Denise McNair in front of her home with her mother Maxine McNair on Mother’s Day 1963(Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

While Lisa knew her parents grieved Denise’s death, her parents didn’t let that dominate the household.

“They didn’t walk around and say, ‘Well, Denise would have done this. Denise would have done that,” Lisa said. “They made a whole life for us and tried to bring us joy and happiness.”

Beyond the photos, Lisa deepened the connection to her sister through her book “Dear Denise: Letters to the Sister I Never Knew.” From 2006 until 2017, Lisa poignantly wrote to her sister as if she was catching her up on her life. Lisa even went as far as describing to Denise certain items a girl born in the 1950s wouldn’t understand, like cable television and Internet.

The book was a cathartic experience for Lisa. With so many changes going on in the country during her childhood, authoring a book had been a goal of hers since she was 14. A friend of Lisa’s suggested that she write the book as if she was talking to Denise. So getting the book published in 2022 was both a goal and a gift for Lisa as she discovered another way to bond with her sister.

“My life was much more integrated than her life was,” Lisa said. “And I wanted to share with the world what it was really like for me being part of the first generation of African Americans to move freely in this country after segregation.”

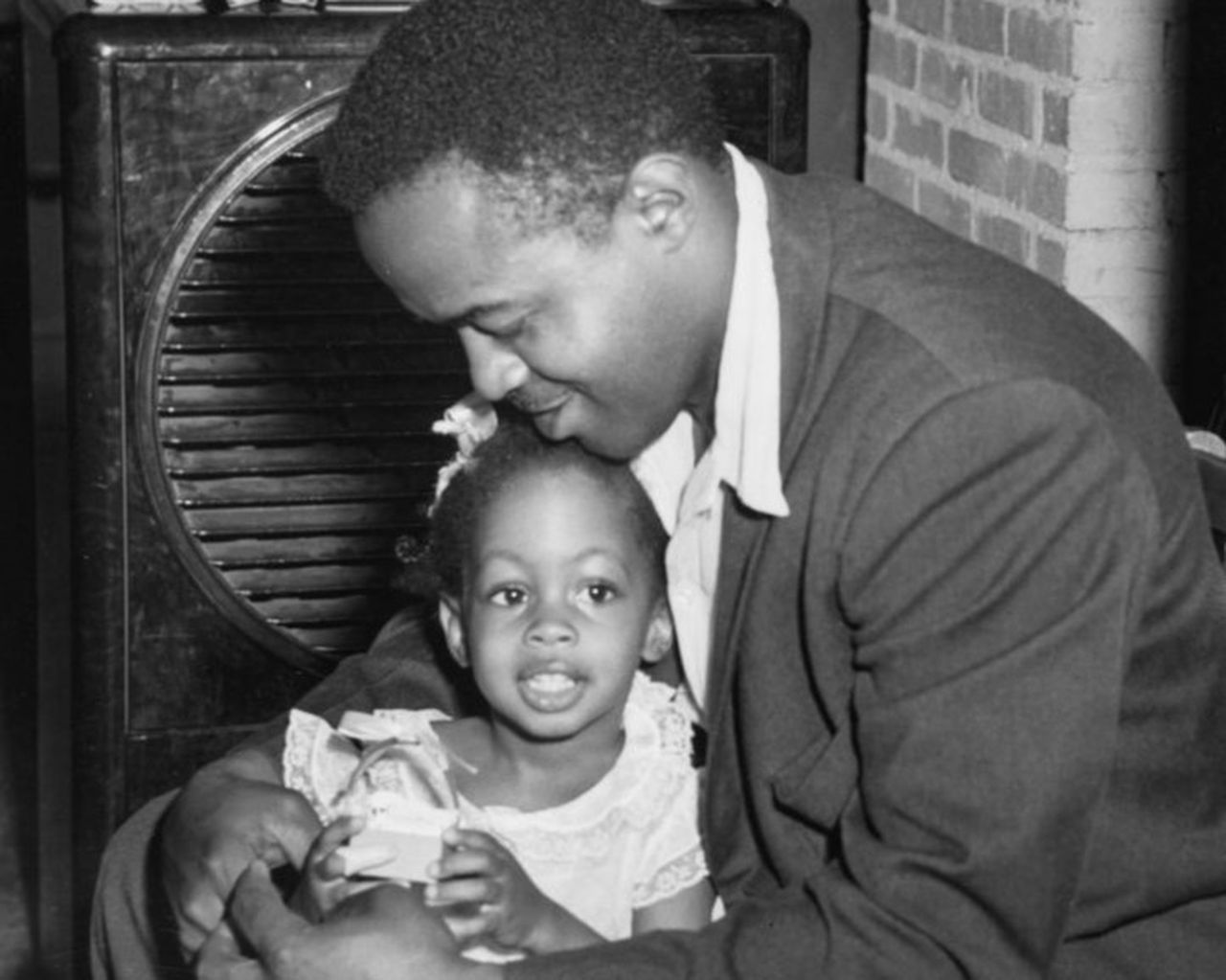

Chris McNair holds his daughter, Denise, in a self-portrait taken around 1954. Denise McNair died in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. Credit Christ McNair. Getty Images.

Chris also played a role capturing the changing racial tides of the nation. The family’s massive photo collection is a loud testament to Chris’ mastery in photography. His camera

was a constant companion of his, putting him in a position to give the world glimpses of the movement work happening in Birmingham at the time photograph by photograph. He had photos featured in Ebony and Jet magazines. Getty Images, which has the world’s largest privately-owned photographic archive, recently reached out to the family to get access to Chris’ pictures.

About a week before the 60th commemoration of the church bombing, Lisa and Kimberly spent a Sunday afternoon peering through a large, black photo album full of prints depicting different angles of the Civil Rights Movement. There’s a picture of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and his attorney Orzell Billingsley leaving Birmingham jail, where King penned the infamous letter criticizing white clergy members for not actively fighting against unjust laws that upheld the status quo of racial oppression. Another photo shows King, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and other prominent Civil Rights legends hosting a press conference after King’s release from jail.

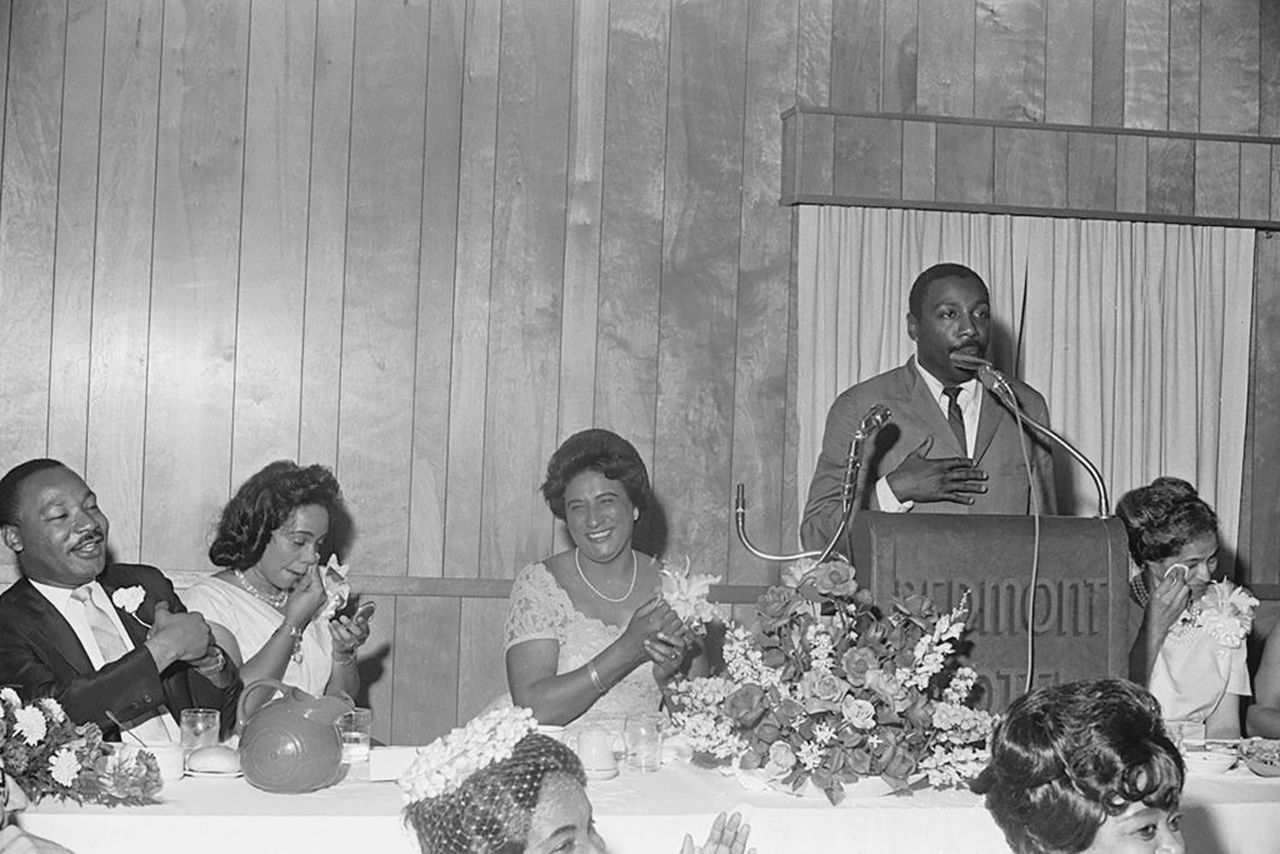

Lisa’s favorite photos are more candid in nature. She smiles down at a snapshot of King and his wife Coretta laughing as activist Dick Gregory cracked jokes during the 1965 Southern Christian Leadership Conference banquet in Birmingham.

“Coretta laughed so hard she messed her makeup up and had to get herself together,” Lisa chuckled. “Seeing them as regular people just sitting in the audience is really cool because they don’t talk about them just attending a conference and having lunch.”

During an SCLC banquet at the Redmont Hotel, American comedian and Civil Rights activist Dick Gregory (1932 – 2017) (standing) speaks from a lectern as, seated from left, married couple Dr Martin Luther King Jr (1929 – 1968) & Coretta Scott King (1927 – 2006), politician Constance Baker Motley (1921 – 2005), and Rosa Parks (1913 – 2005) all laugh, Birmingham, Alabama, August 1965. (Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

The album was just a fraction of Chris’ photography from that time. Lisa said her dad didn’t print his work for about 40 years. Boxes and filing cabinets would be full of his negatives. Lisa and Kimberly are still finding hidden gems in the film and photo slides: family photos of them frolicking in the backyard when they were kids and a snapshot of King’s oldest child, Yolanda, glancing at Chris’ camera during a day out with her father.

Chris started printing his photographs in the late 90s and early-2000s. Although her dad had talked about the history of the photos, Lisa was awed when she first saw the prints.

“I was like, ‘Oh, this is a jackpot here,’” Lisa said. “We want the rest of the world to see these.”

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and Coretta Scott King lock arms while singing at the SCLC Conference on August 10, 1965 in Birmingham, Alabama (Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

Beyond his photography business, Chris forged a political career that started in 1973, when he became one of the first African Americans to land a seat in the Alabama State House of Representatives. He also served 15 years on the Jefferson County Commission before he passed away in May 2019.

In his honor, Lisa and Kimberly curated a free exhibit this fall at Birmingham City Hall that they believe would make their dad proud. Over the past several weeks, onlookers experienced the movement from his point of view. Lisa thinks about the impact of her father’s photos.

“I love that this is his legacy,” she said. “I don’t think he really knew what his legacy was. He thought it was something else, but us and these images are his legacy.”

“They are history,” Kimberly added.

In the back of the photo album, Lisa points to another example of her father’s artistic range: a picture of Denise McNair on canvas. The photo was originally in black and white, but Chris added life to it with colored pencils and his attention to detail. He made sure he got the shading right as the light shines on Denise’s hair. Catch lights sparkle in her eyes.

It’s one of Lisa’s favorite photos of Denise, who she hopes the world won’t forget. Lisa is worried about how politics will affect her sister’s story as lawmakers try to erase and sanitize Black history.

Florida students, teachers and parents are challenging Gov. Ron DeSantis’ decision to ban an Advanced Placement African American studies course. DeSantis also supported a new state history curriculum claiming Black people benefited from slavery. The bans and policies are already affecting the McNair family. Lisa said a Florida school system prevented her from speaking during a civic event in April because school officials were afraid she was going to mention critical race theory.

Lawmakers like DeSantis believe these measures will protect children from being indoctrinated with “woke ideologies.” But Lisa believes this is a matter of white guilt. As more Black people are coming forward to tell their stories of racial trauma, Lisa said white children are asking their family members if they participated in slavery, lynchings or other discriminatory acts, which makes white people feel uncomfortable. But prioritizing white comfort over the truth of history can be dangerous.

“What are you gonna do about that discomfort? That’s the question,” Lisa said. “Black history, such as the history of the girls in the church, is our shared American history. Unless we know our history, we’re destined to repeat our history.”

A portrait of Denise McNair that her father, Chris McNair, shot and colorized with paint and pencils. By Chris McNair. Courtesy of McNair family.