Tropical fish now reeled in off Alabama coast as water temps rise

Gardner Love tugged his fishing line loose from a tree branch over shallow water off Perdido Beach, and seconds later hooked a once rare fish that would easily smash an Alabama record.

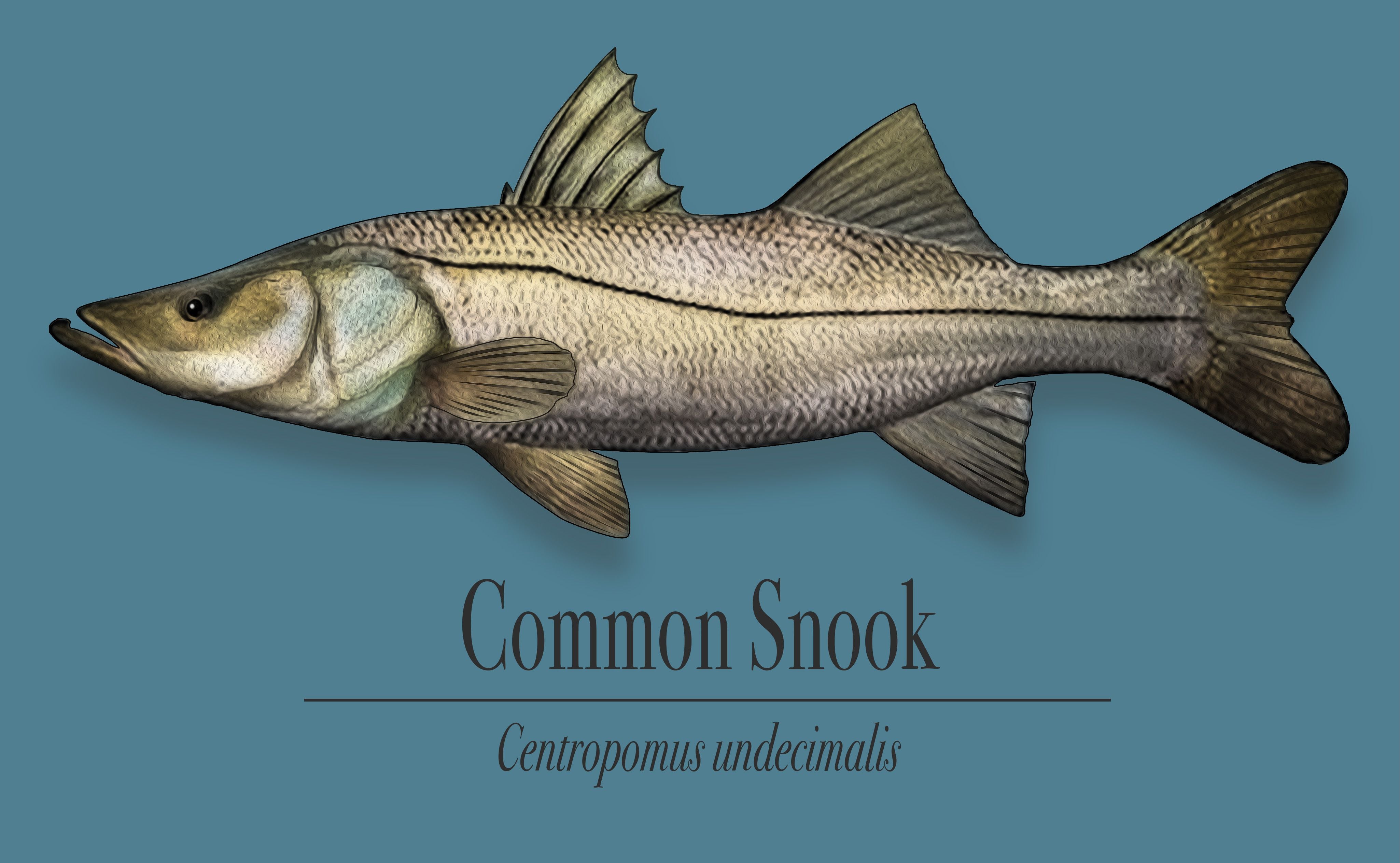

“As soon as it hit the water it was like a big explosion happened,” said the 17-year-old, who found that he’d snagged a common snook, a sportfish that’s popular in south Florida, hundreds of miles away.

Until recently, snook were almost never caught in Alabama.

But as average water temperatures increase globally — including in the Gulf of Mexico — warm water fish like the snook are migrating, showing up in places they’ve rarely been seen.

“The Gulf of Mexico where we sit is supposed to be a temperate environment,” said Sean Powers of the University of South Alabama. “And now it’s definitely becoming more subtropical to even tropical.”

Powers, who chairs the university’s Stokes School of Marine and Environmental Sciences, said it’s called “tropicalization.” As temperatures rise more species from the tropics are shifting north, and snook can be found cruising waters from the Florida Panhandle to Louisiana.

“We see things now in our seagrass beds that we never saw before,” Powers said. “Like parrotfish, which are more things you’d see in the Keys.”

The warming waters are also attracting larger fish, such as sharks.

There are now five times more juvenile bull sharks in Mobile Bay than just 20 years ago, according to researchers at Mississippi State University, LSU and others.

The authors of that study wrote that “slight increases in temperature over that time provided the best explanation for this population increase.”

A 432-lb. bull shark weighed in at the 2024 Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo was just 16 pounds short of the state record. Researchers say juvenile bull sharks are five times more abundant in Mobile Bay than they were 20 years ago, with rising temperatures being the most likely cause. Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

Rising temps

Charlie Martin, an assistant professor at South Alabama, has been tracking the range of tropical fish like snook.

So far, researchers tell AL.com, Alabama is only adding species. That’s been a boon for sportfishing, as the state had to add several tropical fish categories in competitions.

“Snook, we found, had increased exponentially in the panhandle of Florida, and since coming here, I’ve been collecting reports of snook locally [in Alabama],” Martin said.

The common snook, a popular sportfishing target that was historically caught mostly around south Florida, has been popping up in Alabama waters in recent years as water temperatures increase. (Andre Malok | NJ Advance Media)

Snook catches in Alabama don’t happen every day, but seem to be increasing, as do catches of other species previously only seen farther south.

“Things like gray snapper, African pompano, things that weren’t very abundant, now are very abundant,” Powers added.

These tropical fish sightings come as temperatures steadily rise in the Gulf of Mexico, even faster than temperatures in other oceans.

A 2023 NOAA study showed that average surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico have increased by 1.9 degrees F between 1970 and 2020, about twice the increase measured worldwide.

And the temps have been going up even faster over the past decade.

NOAA records show that from 1982 to 2014, just 41% of days in the Gulf had a surface temperature warmer than the 1971-2000 daily average. That means that in those years, the Gulf water temperature was more often at or below recent averages.

But that’s changed. Since 2014, 82% of days in the Gulf of Mexico have been warmer than the historical average.

Those changing conditions are impacting where fishes can survive and reproduce, when and where they migrate and their preferred habitat.

“The Gulf of Mexico where we sit is supposed to be a temperate environment. And now it’s definitely becoming more subtropical to even tropical.”

Sean Powers, University of South Alabama

So far, researchers say, no Gulf species appear to have died off. But there are concerns, as some species butt up against the panhandle with nowhere to migrate northward in search of temperate waters. And some species, like popular Alabama oysters, can’t easily migrate.

Not just the snook

As temps shift, so do seasons.

“We’ve always had that cobia run in March and April and we would see them migrate in,” said Frank Harwell, a long-time fishing boat captain who’s fished coastal Alabama most of his life. “We don’t see that at all anymore.”

Harwell runs the company Coastal Blue Persuasion, offering charters from Dauphin Island, Alabama.

“The fish we look for, we can count on them showing up earlier every year, like the Spanish mackerel,” Harwell said. “The last several years I’ve seen more and more tarpon, along with tripletail, a lot earlier every year.”

Harwell said the gray snapper (also called mangrove snapper) are increasing in abundance.

“That’s something that we never really saw when we were younger and fished a lot,” he said. “We’ve caught a few big ones offshore over the years, but the small ones, they’re like bluegill [an abundant freshwater fish] now in-shore.

“They’re everywhere you go and wildly populated. There’s so many of them, and a lot of the older people I’ve talked to said they never saw that as they were growing up.”

Fishing rodeo adds categories

The Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo — billed as the world’s largest fishing tournament — has run for nearly a century, leaving a record of common catches and a window into rapid changes. They’ve even had to create some new categories. African pompano were once entered in the most unusual category. Since 2018, African pompano has been a category all its own, as more anglers brought them up to the scales.

On the final day of the 90th Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo in 2023, dozens of boats pulled into the rodeo site with anglers ready to weigh in their catch. (Lawrence Specker | lspecker @al.com)

Gray snapper has also been granted its own category since the mid-2000s. Permit, another popular Florida game fish, was good for third place in the most unusual category in 2012. It’s not a category yet, but it’s no longer unusual.

Fish like the pompano and the cobia used to make well-known “runs” or migrations through the northern Gulf, giving fishermen an opportunity to target the prized species. Harwell said it seems that cobia don’t migrate at all anymore, they may just move into deeper waters when the temperature rises.

Federal researchers with NOAA are also documenting range shifts among fish species in the Gulf of Mexico.

Mandy Karnauskas, ecosystem science lead at NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Miami, said NOAA is trying to determine whether species, such as amberjack, cobia, Spanish mackerel, and king mackerel, might be retreating to deeper, cooler waters in the Gulf since they can’t move any farther north.

“We suspect that some of these species might be moving deeper, farther offshore,” Karnauskas said. “That’s an area of active investigation, so we can’t say with any certainty yet.

Now in its 91st year, the Alabama Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo provides a wealth of information about what kinds of fish are caught in Alabama waters. (AL.com file photo)

It’s not just fish that are showing up in unexpected places. The environment itself is becoming more tropical.

Seagrass beds are changing in the northern end of the Gulf, being replaced by mangroves, which historically were killed off by winter cold snaps.

“Mangroves are another species that have been encroaching northward on, actually, all three coasts, the Florida Atlantic Coast, Florida Gulf Coast, and the Texas Gulf Coast,” Martin said. “Black mangroves, as I understand it, now have made it all the way around.”

New state record

Once Love hooked the fish off Perdido Beach on May 14, it didn’t go quietly.

“At first I thought it was a tarpon,” Love said. That’s another popular sport fish famous for putting up a big fight.

But as he reeled it closer to the boat, the fish jumped out of the water, revealing the trademark stripe down the side.

Gardner Love displays his Alabama-state record snook after wrangling it into the boat on Perdido Bay. (Contributed by Len Love)

Love, who works part-time as a deckhand on a fishing boat, fishes Soldier Creek off Perdido Bay on his own all the time. He said he recognized the fish immediately. There was a moment of panic, Love said, when he realized the fish was “barely hooked” and might escape.

He said he didn’t have his net. So, he jumped into the shallow water, grabbed the fish with his hands and flung it inside the boat. Love said one of the treble hooks on the lure he was using had been almost completely flattened out during the fight and probably wouldn’t have held much longer.

He called his father Len. Love’s catch weighed in at just over 7 pounds, smashing the Alabama state record by almost two pounds. But that’s partly because snook are still rarely caught in Alabama.

In Florida, it would not even be big enough to keep. Florida fishing regulations require snook to be at least 28” long and Love’s fish measured 27”. The Florida snook record is 45 pounds 12 ounces.

Shifting species

As researchers and fishermen document the changes happening in Alabama’s coastal waters, it’s uncertain what all the consequences will be in a world that continues to get warmer.

“Right now we’re at the stage where we’re documenting all these changes, but we don’t know the consequence of all of these changes,” Powers told AL.com.

He said that on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, fish are shifting their entire range northward, meaning there are places where they can’t be found anymore.

For now, Powers said, the northern Gulf only seems to be adding new species to its food web.

“So far, we see a lot of species being added, but we haven’t seen any evidence that species are disappearing,” Powers said.

There’s a big emphasis on the words “so far.”

“We see lots of species’ range shifts,” Powers said. “Nothing that I would view as really detrimental yet, but there’s things on the horizon that could be.”

“Right now we’re at the stage where we’re documenting all these changes, but we don’t know the consequence of all of these changes.”

Sean Powers, University of South Alabama

That could include more toxic algae blooms and “dramatic changes in our coastline,” as salt marshes are replaced by mangrove shrubs.

Other fish species, like flounder, might face reproduction issues since temperature determines the sex of offspring.

“We’re very concerned that the [flounder] population is becoming more male over time because of the warmer temperatures,” Powers said. “But that’s only been shown in an aquaculture hatchery setting, and not in the environment.”

Oysters feel the heat

But of all the coastal Alabama species feeling the heat from climate change, the state’s oysters may be in the most immediate danger.

As Mobile Bay has begun to routinely see summer water temperatures approaching or even exceeding 90 degrees Fahrenheit, the oyster crop is taking a hit.

Ricky Harbison Jr. of Coden-based Anna’s Seafood heaves a sack of oysters onto a pallet on Feb. 11, 2020, the last day of Alabama’s oyster season. He and his brother Larry Harbison, in orange apron, were on hand to purchase freshly harvested wild oysters. (Lawrence Specker | [email protected])

“It is a real problem with oysters that we’re experiencing such high extreme temperatures,” Powers said. “That’s going to make the environment less hospitable for the oysters.

“Oysters can’t move, they can’t seek refuge in deeper water.”

Powers and other researchers published a paper in May showing that oyster reproduction plummeted in years that included long-lasting marine heat waves.

Their research showed poor oyster reproduction in Mobile Bay in Alabama and nearby Apalachicola Bay in Florida in 83% of the years that included 11 or more consecutive heat wave days. Those are unusually, historically hot days, when the air soars to a temperature above what was recorded nine out of 10 times on the same date over the last half a century.

The survey showed poor reproduction in only 43% of the years that did not see so many heat wave days. That tracks with what Alabama’s oyster fishers saw last year, during one of the warmest years on record in the Gulf of Mexico, as Mobile Bay waters exceed 90 degrees on numerous occasions.

“I do have a concern for the next two years, for sure,” said Scott Bannon, director of Alabama’s Marine Resources Division, which sets and polices oyster harvest seasons in the state.

Surveys conducted by Marine Resources entering last fall’s oyster season showed a fair number of adult oysters, but very low concentrations of spat, oyster larvae.

“We have not seen a good spat set in the last two years of our surveys, and so that’s concerning,” Bannon said. “We’re seeing harvestable oysters and we’re seeing undersized oysters, but we have not seen that spat, those babies attach, and that’s a concern.”

In the short term, since oysters take 18 months to two years to reach harvest size, that’s a bad omen for the 2025-2026 season.

But there are long-term concerns. Chris Nelson, president of Bon Secour Fisheries in Gulf Shores, said his company began harvesting oysters from Mobile Bay in the 1890s, but now gets most of his oysters from Louisiana and Texas.

Nelson said most of the oysters he gets now from Alabama are farmed rather than wild-caught, and don’t reach the full size that customers expect from a wild oyster, forcing him to look elsewhere.

“There’s not enough, even with both Mobile County and Baldwin County together, plus whatever we would be able to get out of Northwest Florida, is not enough oysters from the farms to be able to satisfy demand,” Nelson said.

Warning from the east

Apalachicola Bay, on the Florida Panhandle about 190 miles east of Mobile Bay, is the poster child for what can happen when an oyster fishery collapses. In 2020, after years of declining harvests, Florida game officials closed the oyster fishery there for five years.

The bay that once produced 90% of Florida’s oysters, and 10% of all oysters in the country, hasn’t officially sent a single oyster to the market in four years. Florida wildlife officials are working to restore the oyster reefs in the Bay and determine whether the fishery can reopen in 2026, or needs to remain closed.

Fresh from Alabama coastal waters, wild oysters sit on a dock after being brought in on Feb. 11, 2020, the last day of Alabama’s 2019-20 oyster season. (Lawrence Specker | [email protected])

Heat waves are not the only condition that stress oysters. Oysters also need the right mix of freshwater and saltwater to survive.

Too much freshwater flowing down from the rivers into the bays can kill off the spat before they can develop into oysters. Too little, and saltwater predators like the oyster drill snail can move in and wreak havoc on the crop.

Numerous factors likely contributed to Apalachicola’s oyster collapse, including overfishing, changes in freshwater flow from the Apalachicola/Flint River system, and warming temperatures. Now researchers are trying to establish the exact causes of the collapse and how they can be avoided.

“The philosophical challenge that we all face is teasing apart all these different co-occurring anthropogenic and natural stressors,” Martin said. “These things are all happening at once. So how do you attribute everything to climate change, or everything to overharvesting, or habitat loss or changes in freshwater inflow?”

But the situation in Florida is a stark reminder that oyster fisheries can come to an end.

For now, off Alabama’s coast, it’s a waiting and a monitoring game. Researchers continue to study oysters and other species to determine if and when rising temperatures in the Gulf will become a major problem.

“We are seeing changes,” Powers said. “If you focus just on the mobile fish, things might seem more positive.

“To the fisherman, more gray snapper is a great thing. Opening up, eventually, a snook fishery in Mobile Bay is a great thing.

“But the loss of oysters is a bad thing. And that’s just a species that we’ve been able to study a little more than the other ones, so we understand the consequences now much more of these extreme high temperatures.”