Warming waters are ‘scrambling ocean life’ on all sides of the United States

Off the coast of Oregon, hidden just beneath the surface, once-towering seaweed forests are beginning to resemble clear-cut wastelands.

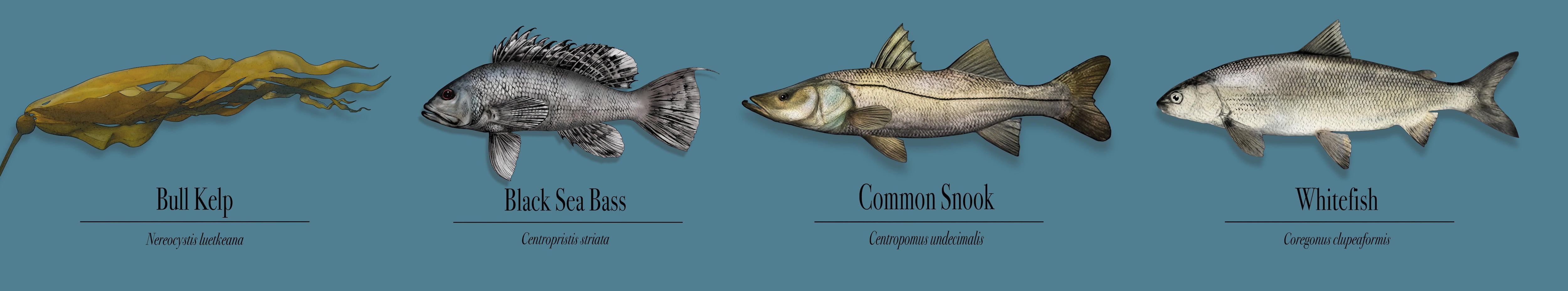

Bull kelp, a giant species of seaweed that can grow 100 feet tall underwater and is known as the “sequoias of the sea,” is dying at a record pace, and so far, it’s not coming back. The kelp forests that formed the backbone of Oregon’s offshore ecosystems, affecting everything from snails to whales, have declined by two thirds since 2010.

“It got so bad, we stopped doing kayak fishing tours,” said Dave Lacey, a boat captain in Port Orford. “We used to pull in about $10,000 every summer. Now that’s totally gone. We just gave up on it. I didn’t want to take people’s money and not catch any fish.”

From the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, rising water temperatures and more frequent heat waves are changing what’s found under the surface, as mass migrations of whole species transform generational fishing business, offshore recreation and even what’s on the menu at local restaurants.

Ethan Hamel (left) and Earl Long (right) work to load whitefish into the sorting bin on Saginaw Bay, MI on Tuesday June 11, 2024. (Santino Mattioli | MLive)

In 2024, Advance Local Media newsrooms in Alabama, New Jersey, Michigan and Oregon set out to document the changes. Some of what fishermen are reporting is sudden, the effects decisive and clear, while other changes are more subtle and still emerging.

Scientists are just beginning to document the changing patterns, as they tease apart how warming waters affect ecosystems influenced by many variables. For now, scientists are sure things are getting hotter, and the fishermen are sure marine species are on the move. And no one can say for certain what comes next.

“One of the things that keeps me up at night is … in addition to all the changes we’re seeing, we know there are going to be big surprises,” said Malin Pinsky, a professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources at Rutgers University.

“And those are going to likely disrupt our economies, likely disrupt the ecosystem — the ocean ecosystems — that we rely on,” he told NJ.com.

(Andre Malok | NJ Advance Media for NJ.com)

Off the Atlantic coast, the lucrative black sea bass are heading farther and farther north as water temperatures increase. That’s a boon for New Jersey, where fishing operations are expanding, but not so much for North Carolina, where sea bass numbers are plummeting.

The change is so rapid that the government can’t keep up. Even in places where black sea bass are thriving, outdated limits mean they can’t be caught.

“This commercial quota has needed, and can easily sustain, an increase,” Patrick Knapp, a Rhode Island fisherman, wrote to regulators. “The science is there and so are the fish.”

In the Gulf of Mexico, tropical fish like snook are making their way north, where sportfish competitions off Alabama have added categories for colorful species that are normally found in the Florida Keys. While amateurs welcome the tropical catch, warming temperatures are disrupting the patterns of popular fishing targets, as oysters and corals struggle to hold on in their historic ranges.

“We’ve always had that cobia run in March and April and we would see them migrate in,” said Frank Harwell, a long-time fishing boat captain who’s fished coastal Alabama most of his life. “We don’t see that at all anymore.”

Even the Great Lakes are affected, as there isn’t as much ice cover as there used to be. That means the whitefish hatch earlier, making them more vulnerable to predators. At the same time, invasive mussels are gobbling up their food, throwing a historic fishery into turmoil.

“If there is enough ice cover over them and they do hatch, they’re having a hard time finding food up until about age 2,” said Lakon Williams of Bay Port Fish Company, which still operates two fishing boats on Lake Huron.

In Oregon, the loss of the kelp forests is leading to changes big and small, from a drop in the commercial red sea urchin harvest to a decline in recreational fishing near the shore to the complete disappearance of red abalone snails. It’s like a forest with no trees, and nowhere for the snails and fish to live, said Sarah Gravem, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University.

“We went snorkeling one day and there was zero kelp, except for this one old kelp from the year before that had made it through,” Gravem told The Oregonian/OregonLive. “I dove down to the bottom on this scraggly looking, ugly kelp and on the kelp’s holdfast there was a single abalone licking the stem. And about 17 urchins were on its back and coming up behind it and this abalone was just trying to shake them off. It was the most heartbreaking moment.”

The last 10 years

By most measures, 2023 broke records. Analysis done by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed 2023 was the hottest year on record in North America, South America and Africa. It was the second warmest year ever in Europe and Asia.

The global surface temperature rose higher above its historical average than ever before last year. And many areas are continuing to break heat records in 2024.

While the change in temperature is evident and easily documented, the impacts are harder to suss out.

Recording ecosystem-wide changes is a difficult and slow process that often takes years before trends clearly emerge, Dana Infante, chair of Michigan State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, told MLive.com.

“This isn’t an overnight thing because we also know there are natural fluctuations, right? We want to be sure that the changes that are being detected are real,” Infante said.

“The warming has been the most dramatic in the last 10 years. We’re just on the cusp of researchers really starting to get some literature out that documents changes.”

For many of these changes, there are more factors than just temperature to blame. Invasive species are taking a toll in Michigan. Plastic pollution is affecting marine life off New Jersey. Changes in freshwater flow can be devastating to Gulf oysters. Hordes of purple urchins, emboldened by the disappearance of their predator, are devouring kelp in Oregon.

But warming waters seem to be a common culprit.

“Climate change is scrambling ocean life in many ways right now, including warming waters, loss of oxygen, and more acidification than we’ve seen historically,” said Pinsky, the Rutgers professor. “It’s pushing fish and other marine life to new locations and driving them to disappear from places that we’ve relied on them (to be) for decades and centuries.

“All of this then affects our fisheries and affects our coastal economies and eventually affects the food that ends up on our dinner plates and ends up in the global supply chain.”

Captain Art Unkefer from the fishing boat Rufus II watches ice being poured on black sea bass on a dock in Sea Isle City on Saturday, May 25, 2024. (Jim Lowney | For NJ Advance Media)

Dinner plates have already been impacted.

The Atlantic northern shrimp population in the Gulf of Maine collapsed after a record-setting marine heat wave in 2012. Research has shown that warmer temperatures hurt the shrimp’s ability to reproduce, and made the waters more palatable for the longfin squid, a voracious predator that took a toll on the northern shrimp.

“My first reaction when I saw the 2012 survey data was shock, perhaps even horror, and disbelief,” said Anne Richards, a retired biologist formerly with the Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass.

“Though recruitment had been down in the previous years, we would not have expected to see the bottom fall out of the adult population like that. It was unprecedented,” she told NJ.com.

Since 2013, the fishery is still closed and has not recovered, and its future is very much in doubt.

“Not all species react the same way to climate change,” Richards said. “So there will be new suites of species coexisting that hadn’t really interacted before, with perhaps unpredictable results.”

In Alabama’s Gulf Coast, researchers found a direct link between oyster harvests and marine heat waves — consecutive days where the temperature far exceeds the average for that date.

Fresh from Alabama coastal waters, wild oysters sit on a dock after being brought in on Feb. 11, 2020, the last day of Alabama’s 2019-20 oyster season. (Lawrence Specker | [email protected])

Oyster reproduction plummeted in years that included long-lasting marine heat waves, according to research by Sean Powers, chair of the University of South Alabama’s Stokes School of Marine and Environmental Sciences and other researchers.

“It is a real problem with oysters that we’re experiencing such high extreme temperatures, and that’s going to make the environment much less hospitable for the oysters,” Powers told AL.com.

Bottom-dwelling Atlantic surf clams have also suffered from warmers waters off New Jersey’s coast in recent years.

In the Florida Keys, there has been a lot of attention on coral reefs, bleached by the heat.

Mandy Karnauskas, Research Fishery Biologist and Ecosystem Science Lead for NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Miami, said that 2023 was an especially bad year for corals in the Florida Keys.

“We have really clear evidence on how that heat stress and these heat waves impact our corals, and last year, we actually had a really bad year,” Karnauskas said. “In 2023 the ocean was really hot. I know we had some buoys out in the coastal areas, but well offshore where the temperature was actually over 100 degrees Fahrenheit.”

According to NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program, some coral types such as elkhorn corals are particularly vulnerable. NOAA noted that of 160 elkhorn coral genotypes documented in the Florida Keys, only 37 remained in fall of 2023.

“Climate change is scrambling ocean life in many ways right now, including warming waters, loss of oxygen, and more acidification than we’ve seen historically.”

Malin Pinsky, professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources at Rutgers University

In April 2024, NOAA warned the planet was experiencing a global coral bleaching event, the fourth documented in the past decade.

Coral bleaching is when a normally vibrant, colorful coral turns white due to stress. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the coral is dead — they can recover if conditions improve — but it means the coral is in dire straits.

Off the coast of Oregon, the bull kelp acts much like a coral reef, creating a refuge that sustains a chain of wildlife. Now researchers and nonprofit groups are beginning to try to restore that ecosystem by regrowing kelp forests that are disappearing fast.

Members of the Oregon Kelp Alliance enter the Pacific Ocean on May 24, 2024 to snorkel and dive in one of Oregon’s last remaining kelp forests, at Cape Arago State Park near Coos Bay. (Gosia Wozniacka / The Oregonian)

Part of the problem for the kelp was the disappearance of the sunflower sea star, which turned out to be a key cog in the ecosystem. The sea stars eat purple sea urchins, a round, spiky invertebrate that eats kelp like a teenager eats french fries.

“I don’t think the outbreak was triggered by global warming. But the warmness made everything worse,” said Gravem, the marine ecologist at Oregon State. “It’s clear the stars died a lot faster in warmer waters than in colder.”

When the sea stars suffered huge losses beginning in 2013, the urchin populations exploded, with the hungry echinoderms devouring the underwater forests. Now, efforts are underway to replant the kelp and breed and reintroduce the sea stars to rescue Oregon’s iconic marine ecosystem. But it’s a tall order.

Aaron Galloway, a marine ecologist at the University of Oregon who regularly dives off the Pacific coast for his research on the sea stars, said he’s not sure what comes next for the great kelp forests.

A bull kelp’s air-filled bladder floats up to the surface off the Oregon coast, its fronds or blades providing a perfect hiding place for tiny baby fish. (Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Marine Reserves Program)

“I’m somewhat optimistic that there’s going to be some recoveries, but it’s also a time of great sadness,” he told The Oregonian/OregonLive.

“I mean, there’s so much change happening in the ocean. I’m not sure what’s going to be here in the future.”