Retired Illinois politician recalls encounters with Martin Luther King Jr. while in Montgomery

Jesse White recalls a request made of him and a dozen freshman pledges to Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity to attend a Montgomery church service in the early 1950s.

The request came from the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, a mentor to the minister scheduled to preach that Sunday inside a small church in northern Montgomery. Abernathy was a “big brother” to the Scroller Club that consisted of fraternity pledges at what is now Alabama State University.

“His friend, Dr. King, had come to Montgomery, so we went to the church one Sunday morning, and as it turned out there were about 32 of us,” White recalled Friday with AL.com. “We were inspired by this man’s spoken words that we ran back to the college campus and sang this man’s praises. We were so inspired by him and impressed by him.”

He added, “The next Sunday, there were 75 to 80 people at the service. It was bursting at the seams. He was later promoted to Dexter Avenue (Baptist) Church.”

White, 88, has been recalling a lot about his encounters with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in recent weeks. His recollections include once confronting King for his famous non-violent approaches toward desegregating Montgomery’s buses.

White’s tales have been published in recent weeks in The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun-Times, and beyond. They are included in profile stories about his lengthy political career that ended last week with his retirement following a 24-year tenure guiding the Illinois Secretary of State’s office, among that state’s largest agencies.

First elected in 1998, White is the longest-serving Secretary of State in Illinois. He is also the longest-serving Black Secretary of State to serve in state government in U.S. history, according to the National Association of Secretaries of State.

White’s political career encompassed 47 years that started in 1975 as a member of the Illinois General Assembly representing one of the most diverse political districts in Chicago. He served six years as the Cook County Recorder of Deeds in the 1990s before he was elected Secretary of State.

A lifelong Democrat, White became one of the most popular politicians in the state and once carried every Illinois county in a statewide election, not an easy accomplishment in a state known for bruising politics in Chicago and filled with conservative counties in its central and southern regions.

“He’s probably one of, if not the most honorable and decent public officials we’ve ever had,” said Charles N. Wheeler III, director of the Public Affairs Reporting Program at the University of Illinois at Springfield from 1993-2019, and who was a reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times for 24 years before that. “Based on the voting totals, he’s probably been the most popular and best respected of all statewide officials we’ve had in certainly the last 25 years.”

‘Wonderful, pleasant man’

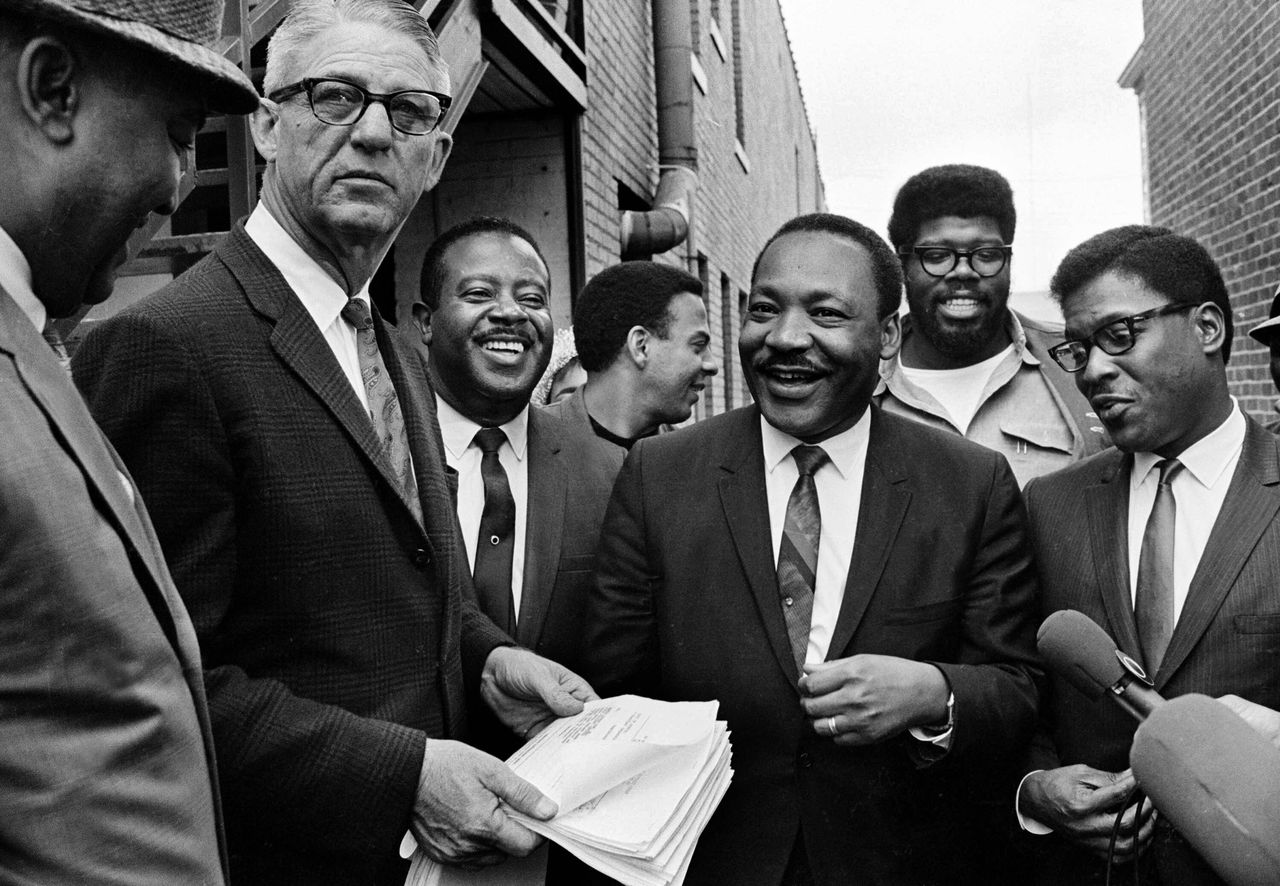

Martin Luther King Jr., center, and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, third from left, share a laugh outside court in Decatur, Ga., Oct. 25, 1960. Others are unidentified. Andrew Young is seen at center, facing right. (AP Photo)AP

The journey to a celebrated political career was rooted in White’s time in Alabama, and he points to the influential encounters he had with King for inspiring his public life.

White’s encounters with King, Wheeler said, were largely unknown to Illinoisans until recent weeks when media pieces have included anecdotal stories about them.

“He (King) taught us a lot about being good citizens, good human beings and loving our fellow man and not disliking anyone because of race, creed and color,” White told AL.com. “And to make sure you got a good education and that we were on time and in school every day. That has stuck with me.”

A $20 gift after basketball games wasn’t so shabby either. King would slip White the money knowing that he came from a poor family in Chicago.

“I didn’t see him that much on campus,” said White. “But he would go (to) every basketball game. He gave me $20 every game. At that time, it was legal. It would not be legal today.”

That $20 in in the 1950s equates to about $220 today.

“Whenever he came on the campus, people would gather around him and hear his spoken words,” said White. “He was a gentleman in every way. He set a good example for us. A wonderful and pleasant man.”

Derryn Moten, chairman of the history and political science department at Alabama State, said White’s recollections “underscore King’s reputation for being approachable” and his camaraderie with Alabama State College students” during the 1950s.

“I think students energized Dr. King,” said Moten. “Stories of King ambling across campus and engaging in conversations with students are legendary. It should also be noted that the Kings were neighbors of the college and were friends with many of the faculty and staff who also knew (him) as their pastor.”

Buses and water fountains

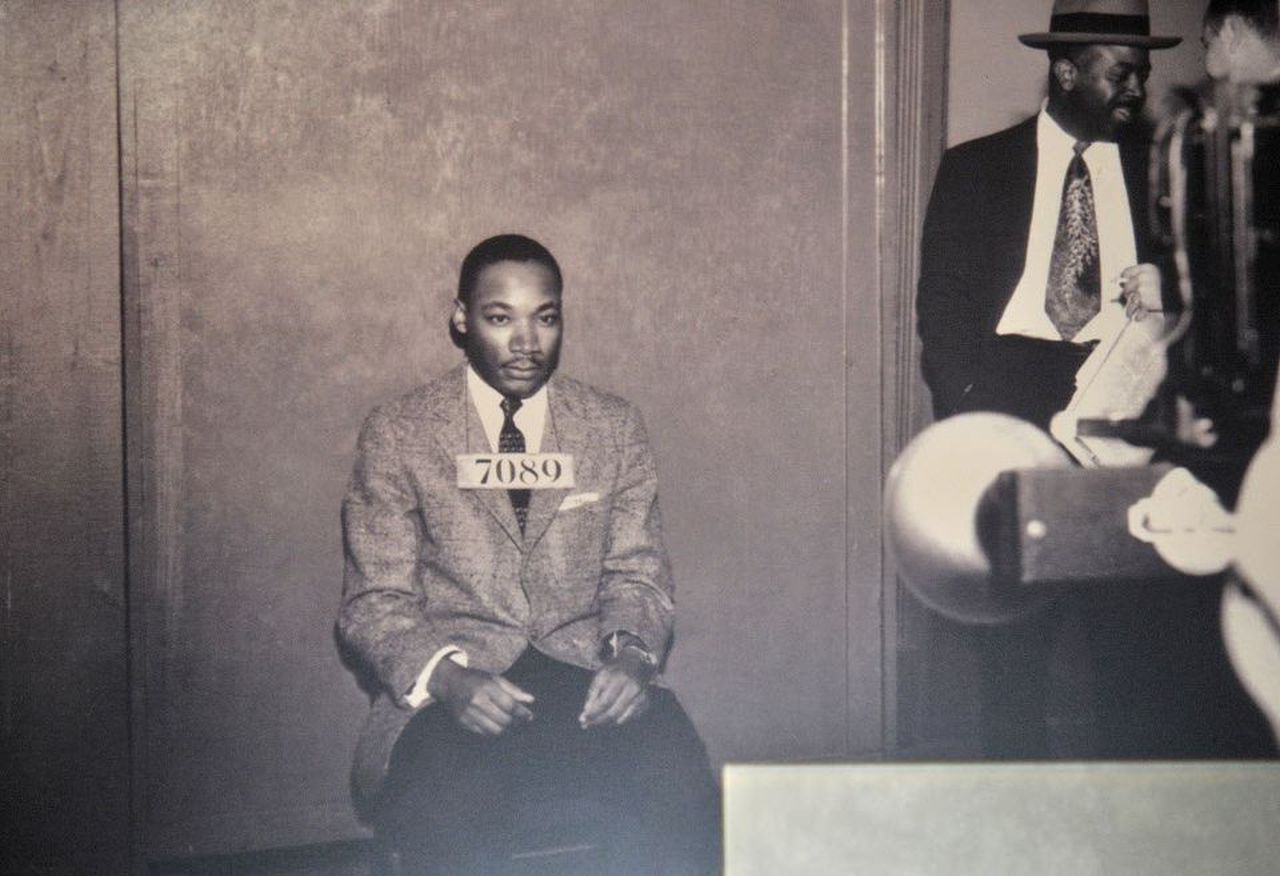

Montgomery photographer Paul Robertson shot this photo in 1956 of Martin Luther King Jr. having his mug shot taken by the City of Montgomery Police department during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. (Photo courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History)

White’s arrival to Montgomery and his encounters with King almost did not happen.

His college applications were turned down at Beloit College in Wisconsin and at several other institutions in the Midwest. White said he did not have the required “sequencing” in mathematics to gain admission into those institutions.

“So, Alabama State took me,” White said.

White came to Montgomery from Chicago in 1952, after having a prolific high school sports career at (Chicago) Waller High School (now Lincoln Park High School). He once scored 59 points in a high school game, and he remains proud — if not a tad boastful — about the quality of his jump shot more than seven decades after his playing days.

“They credited me with bringing the jump shot to the South,” White said.

White is a decorated college athlete in Alabama. He was inducted into the Alabama State University Sports of Hall of Fame in 1999, and the Southwestern Athletic Conference Hall of Fame in basketball and baseball in 1995.

Though statistics from his Alabama State days are not easily found, White’s profile on the Illinois Basketball Coaches Hall of Fame includes some high praise. Norman Watson, an ASU history professor, and swimming coach, compared White’s game with NBA legend Michael Jordan, and said he “came along ahead of his time.”

Alabama’s Jim Crow laws on public transportation in the 1950s almost upended White’s college and athletic career. He said he had a verbal altercation with a Montgomery bus driver a few years before Rosa Parks was arrested in late 1955 for refusing to give up her seat to a white man.

“The first day (I was in Montgomery), I sat behind the driver and the people in the back where African Americans who were yelling and screaming for me to move to the back of the bus,” White recalled to AL.com in a story he has also retold to other media outlets this month. “The bus driver heard the ruckus and saw me sitting behind him. He said, ‘Can’t you read?’ He said that I was supposed to sit behind the sign and that the rear (of the bus) is for colored (passengers). I said that it’s your job to drive the bus, and that I’m required to pay the fare and I did so. He said, ‘I’ll fix you.’”

White remembers the driver parking the bus and exiting at a Texaco gas station in Montgomery. With the driver gone, the Black passengers shouted at him, ‘Where are you from?’”

White responded that he was from Chicago.

“They said that they will beat you up and lock away the keys,” White said, recalling that he was unfamiliar with the segregation rules on the Montgomery buses at the time. “The next time, I went to the rear. I was caught off guard.”

White also remembers a time he traveled from Montgomery to Chattanooga, Tenn., and disobeying the segregated water fountain signs.

“One said, ‘colored’ and the other said ‘white,’” said White. “I drank out of the white one and (the property’s) caretaker said, ‘Boy, can’t you read?’ I said, ‘What is the problem?’ He said there is one for coloreds and one for whites. I happened to have my driver’s license with me and told him that my name is Jesse White. I was being a smart ass. He was beside himself, and I showed him my driver’s license.”

Challenge and respect

White’s rebellious approach toward the segregated norms of the South led to him once challenging King.

“He (supported) the non-violent means to bring that about,” said White. “I said, ‘Dr. King, you know and know me well and I’m from Chicago and we don’t operate like that.’ He said for me to just follow the script and we’ll bring about desegregation of the Montgomery transit system.”

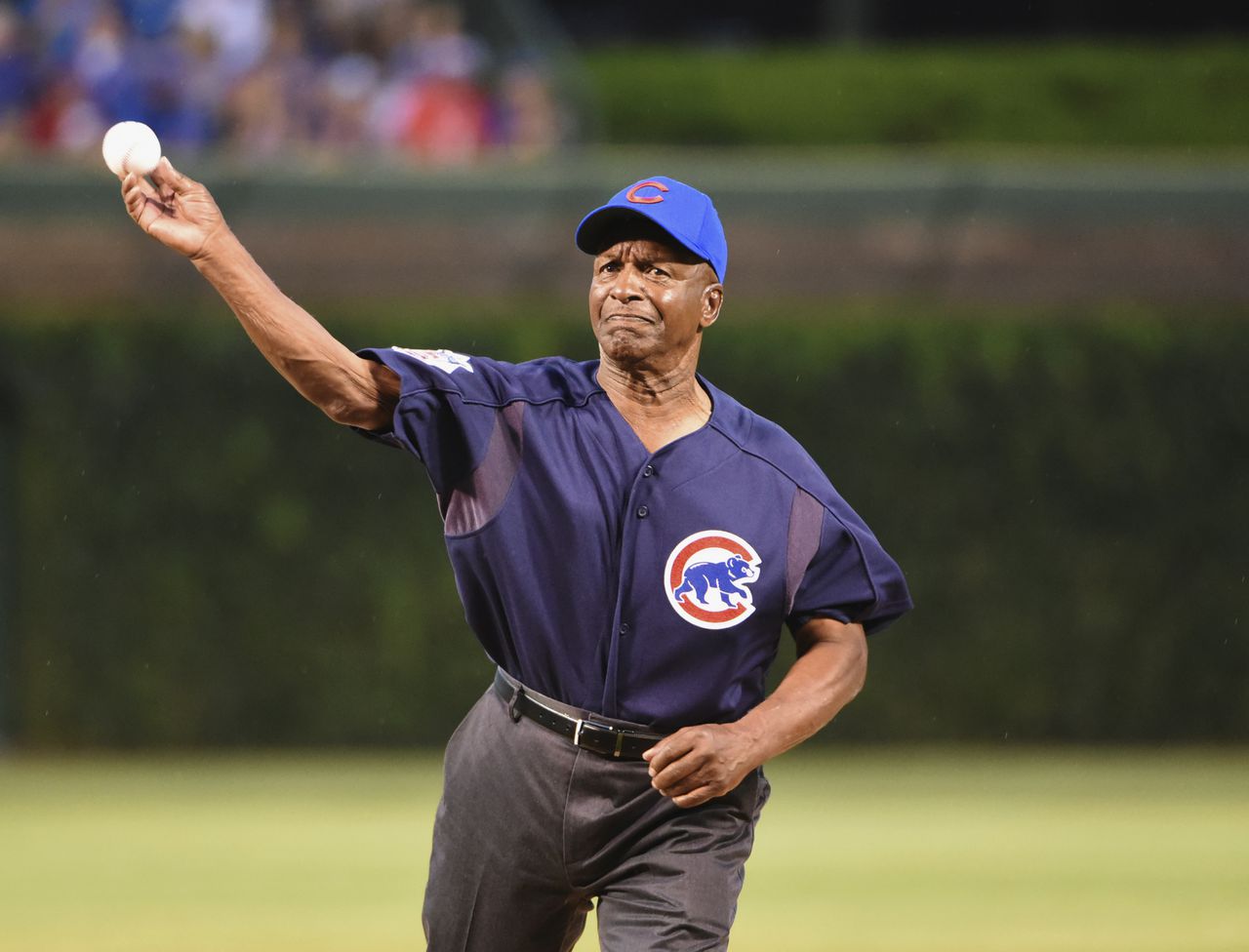

Illinois Secretary of State Jesse White throws out a ceremonial first pitch before a baseball game between the Chicago Cubs and the Pittsburgh Pirates, Monday, Aug. 29, 2016, in Chicago. (AP Photo/David Banks)AP

White’s journey after Alabama State and before his political career included stints as a solider, a seven-year tenure in professional baseball with the Chicago Cubs organization (getting as high as Triple A ball), as an educator and administrator with the Chicago Public Schools, and as founder of the Jesse White Tumbling Team that serves a positive alternative for children residing in the Chicago area.

“They have to be leafless, smokeless and pipe less,” said White, referring to the youths who have participated on his tumbling team since 1959. He estimates over 18,500 young people who have gone through his tumbling program over the years. The program still exists, and White said he plans to get more involved with it now that he is retired from politics.

The students, he said, subscribe to a program of “no smoking, no drinking, no swearing, no doping or dropping out of school” and maintain good grades.

The encouragement to get good grades is something King instilled in White and his fellow Alabama State students in the 1950s, he said.

White’s memories about King also include reflecting on where he was in 1968, after the civil rights icon was assassinated in Memphis.

“I said, ‘you got to be kidding me,’” White said, recalling that someone at the school where he was teaching informed him that King had been shot and killed at the Lorraine Motel. “I took it hard. I knew him. I had much respect for him, and I knew he had a lot to offer in this wonderful country of ours. He gave a lot and there was a lot more for him to give.”

White said he can still hear King’s voice and recall the conversations he had with him some seven decades ago.

Said White, “He brought the races together, he spoke from the heart, and he lived the kind of life that all of us emulate. He had a message about citizenship and brotherhood and about making the quality of life a lot better. I speak about him on a regular basis to my young people (on the tumbling team) and encourage them to follow in his footsteps and do all they can to be the best they can be. The only time I want them to look down is to tie their shoes.”