Roy S. Johnson: Ryan Howard invites Birmingham Negro Leaguers to ‘MLB at Rickwood Field’

This is an opinion column.

“He wasn’t really that good of a hitter.”

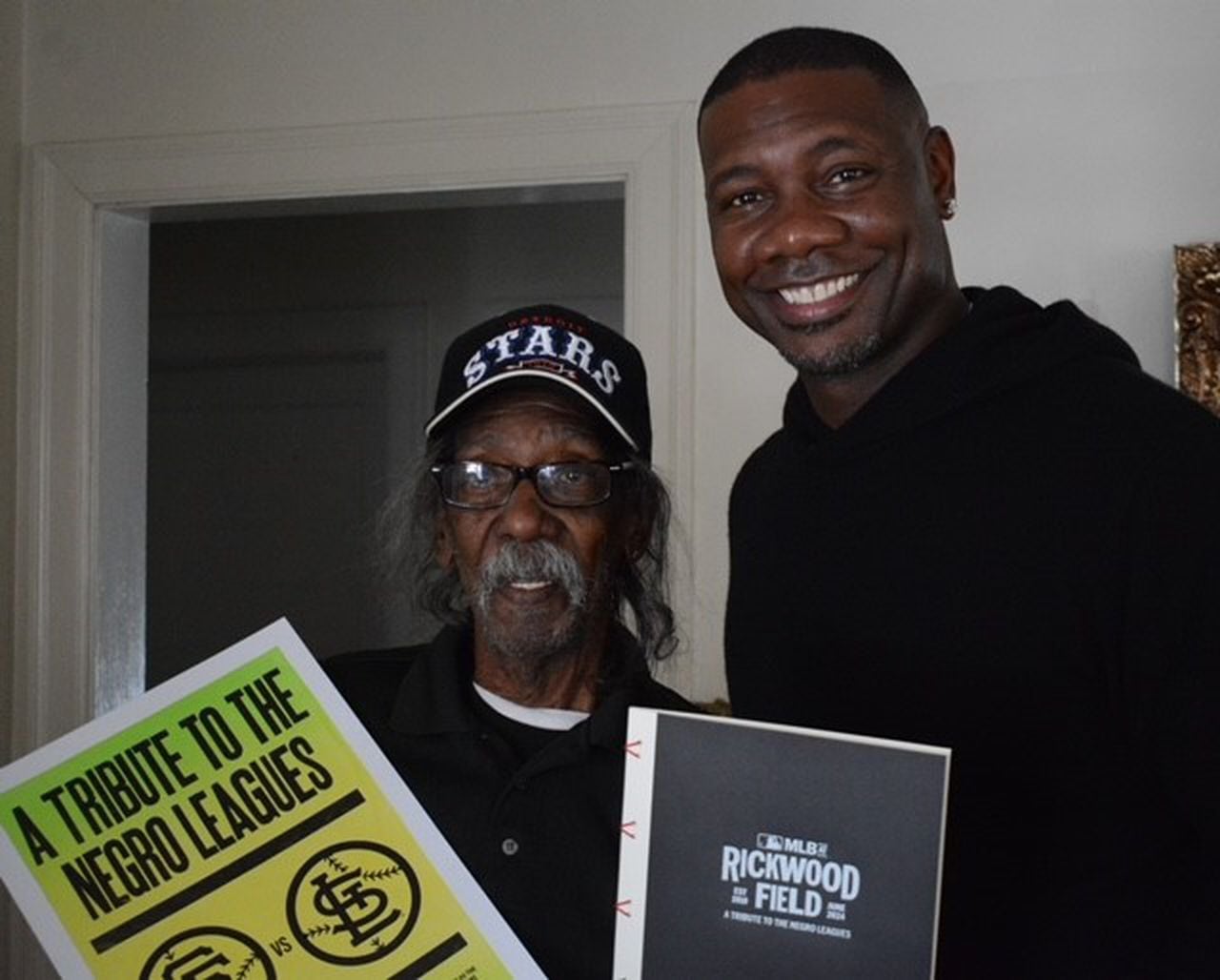

Clinton “Tiny” Forge is a man of few words, and when he speaks it’s barely above a whisper. Yet he knows what he knows. Once a catcher for the Detroit Stars, one of the charter teams of the Negro National League, Forge knows baseball. Knows hitters.

He knew one when he saw one, and the “he” Forge was referring to, well, wasn’t really that good.

“He” was a skinny teenager with a cross-handed grip—a fledging shortstop with the Indianapolis Clowns who signed with them in 1952 for $200 a month. (About right for the Negro Leagues; Forge earned $150.)

“He” was a kid out of Mobile, Alabama. A kid named Hank Aaron, baseball’s future home run king.

“I don’t know how he became such a good hitter.”

Everyone gathered in Forge’s living room in Birmingham one recent afternoon laughed at the recollection, delivered with a wry smile beneath a grey handlebar mustache. Among them and towering over the diminutive former player was Ryan Howard, the former three-time Major League Baseball All-Star with the Philadelphia Phillies, who also knows a bit about hitting. A first baseman, Howard had 382 home runs in 16 seasons.

The men were kindred spirits separated by generations but connected by a game played today mostly just as it was decades ago. “As a catcher,” he asked Forge, “could you tell if a batter knew what pitch was coming by how they adjusted themselves in the batters’ box—then change the pitch?”

“Yes, sir.” His eyes said even more.

“Yeah,” Howard said with a smile, “I know you did.”

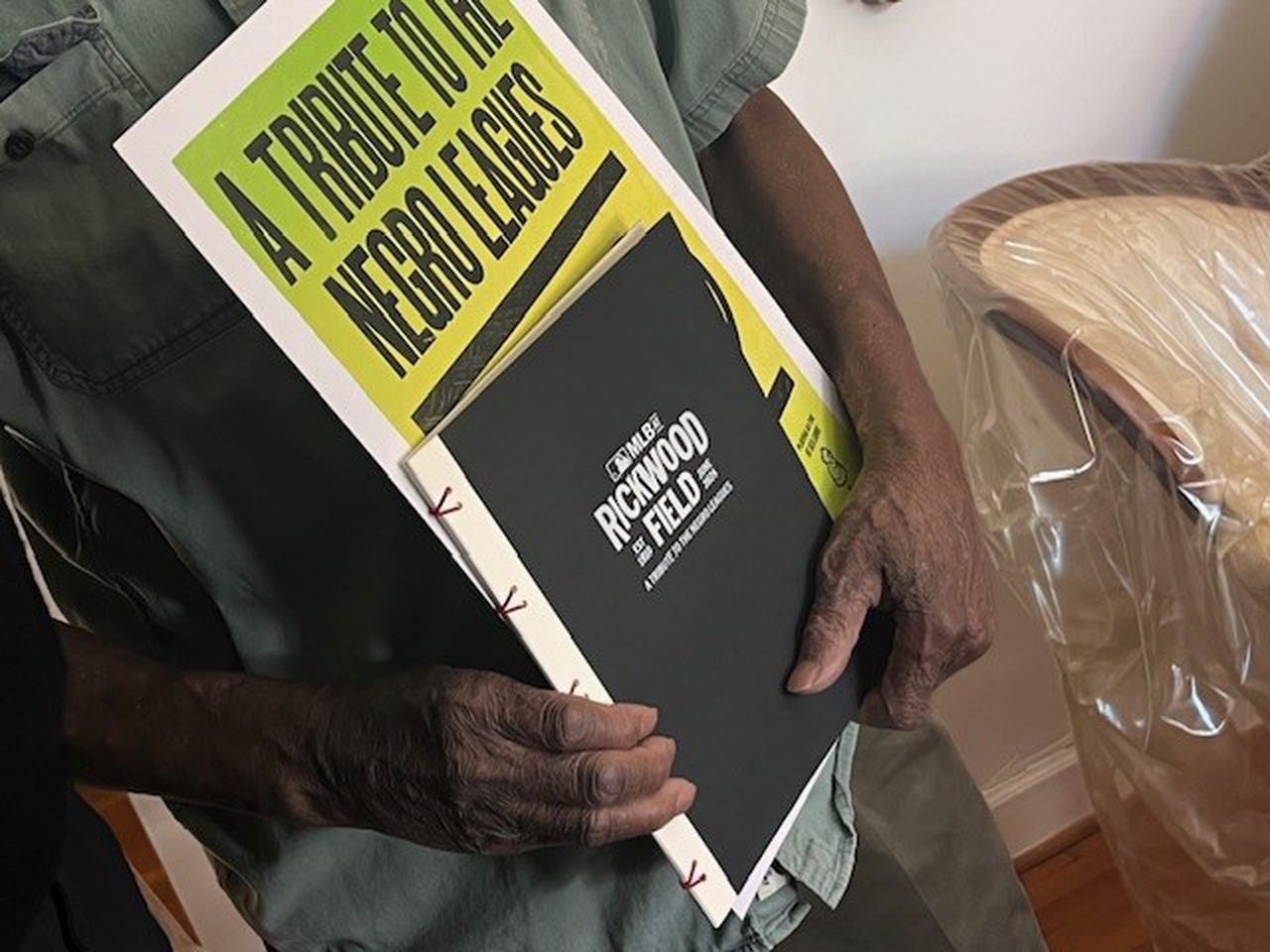

Howard was in Birmingham, where his parents’ family once lived, with MLB officials to deliver personal individual invitations to “MLB at Rickwood Field: A Tribute to the Negro Leagues”—the much-anticipated regular-season game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants on June 21, 2024—to several former Negro League players still living in the city.

On a clear, crisp day, Howard visited the homes of Joseph “Bull” Marbury, Ernest “Oink” Harris (“I was told I was a pretty big baby.”), Alphonse Holt, Ferdinand Rutledge, Charles Willis, and Rev. William Greason. Former Negro Leaguer Walter Kegler received his invitation at the Southern Negro League Museum.

Howard lingered with each of them—hearing stories of a joy for baseball that fueled them to endure, allowed them to compete when for years they were barred from the “majors” (let’s be real: the white majors), and gave them the pride and dignity of knowing, and showing, they could play with anyone.

A rare dignity in undignified times.

“We stayed in private homes sometimes because nothing else was available,” shared Marbury, a big-hitting outfield from Leeds who played two seasons with the Clowns (’57 and ‘58). “In Hannibal, Missouri, we had to stay in a nursing home for about five days. We played during the day and stayed in the nursing home at night. We didn’t like that, but it was the only thing available.”

Everything else, of course, was available for whites only.

Marbury recalled a teammate who “looked white.”

During a trip through Mississippi, the players sent him through the front door of a place that didn’t allow Blacks. All went well, he ordered food. “For some unknown reason he pulled his cap off. They saw that kinky hair and ran him out of there.”

It’s a bit easier now, with decades in the rear-view mirror, for the men to find strands of humor in the hell that was their truth.

Marbury told another story involving the light-skinned teammate: During warmups before a game in Nashville (yes, these men remember) a white man in the stands shouted, “That white guy is the best player out there!” In his first at-bat, the player hit a home run. He “crushed it,” Marbury said.

“That white boy can play, he’s the best player out there,” the fan shouted.

The player hit a double in his next at-bat. As he slid into second base, his hat came off.

“Oh, here we go again,” Marbury said. “The white guy was like, ‘We’ll I’ll be blankety-blank. That’s a blankety-blank ‘n…’, too. It’s funny now but it wasn’t funny way back then.”

Most of all the men talked baseball. Howard asked Forge what size bat he used: “Thirty-five ounces.”

“Whoa,” Howard responded. He used a 35-inch bat that was 34 ounces. Howard is 6-4 and played at 250 pounds. “Tiny,” relatively, is, well tiny.

Harris played for the Birmingham Barons in 1959 and part of the following season in the minor leagues after being signed by the Phillies. The team was based in Bakersfield. Howard asked him if he could hit. “Oh yeah, I could hit,” Harris said with a smile. “I could lay it down. When I bunted, you’d better get ahold of it, otherwise, I’m gonna beat it out.”

The room laughed.

“Those are nuances that in my mind will always be a part of the game, no matter how much the game tries to change,” Howard said. “It’s so cool because the base of the game is always going to be the same—from when these gentlemen played it to wherever it is in the future. The bones of the game will be the same.”

In between visits, Howard paused: “It’s more than just hearing about the long bus rides, the equipment, baseball stuff like that. It’s the feel of the history—real-life segregation and not being able to go into some places, even just to eat.”

“You hear about it when you see you see these guys and you hearing about it firsthand, it just brings it all truly, truly to life and truly into perspective–what they had to go through in the real-world issues aside from the game stuff they had to go through, too.”

Howard was born and reared in St. Louis, though his parents often dropped the young boy off with family members in Birmingham when needed “by themselves” time. His grandfather played in the amateur area coal-mine leagues comprising teams. “He was recruited to play in the Negro Leagues but by that time he already had a family. He had a steady job, so he had to pick.,” Howard said. “He had to take care of his family, so he stayed working.”

Ryan rose to success in the majors as a feast-or-famine talent—either hit a homer or strikeout (he did 1,843 times. An uncle once told him, “You’re just like daddy, he either hit a homerun or struck out.’ I said, “I’ll take it.’

“[Playing in the big leagues] was always an honor because I felt I was carrying [my grandfather’s] lineage through. He didn’t get the opportunity because he took the responsibility to stay in the mines and take care of his family. He was with me. he out there playing with me every time I played in the big leagues.”

Before leaving Harris, the former Negro Leaguer reached into his shirt pocket and handed Howard a baseball card with a photo of the young outfielder and stats. “Very cool,” Howard said.

Time is chasing each of these men, these living testimonials to leagues that never should have been—and should have endured in some form once the majors erased its color line and began draining the Negro Leagues of its talent. Of its life.

Until they were no more—except in the still-sharp memories of the men and women (like Toni Stone, who replaced that skinny teen from Mobile at shortstop for the Indianapolis Clowns after the left to swing towards history) who lived them, who endured.

Just over three years ago, MLB finally acknowledged the talents it once shunned by formally embracing their statistics and records into their own. Commissioner Robert Manfred called it “long overdue.”

And yet there is still more to do—such as expanding pensions, payments for memorabilia sales, and medical benefits.

Before time catches them all.

I’m a member of the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame and a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary. My column appears on AL.com, as well as the Lede. Tell me what you think at [email protected], and follow me at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj