How I teach Black history in Alabama: ‘Vibrant’ inspiration from superheroes

This profile is part of a series. Read more about educators in Auburn from The Alabama Education Lab.

Krystle Smith, a self-proclaimed Marvel fan, was teaching an eighth grade history class when the movie Black Panther came out.

Since the film’s release in 2018, the South Alabama teacher has used the Marvel blockbuster to incorporate African history in several of her social studies classes at Spanish Fort High School and other Mobile County schools, and has even developed a course inspired by its themes.

“When I went and saw the movie, I just had one of those, ‘Oh my gosh, this is exactly what I’m teaching’ moments,” Smith said.

The next day in class, Smith sat down with a student who had also seen the midnight premiere, and together, they started mapping out lessons. The next year, she started showing the film to her middle school ancient history class.

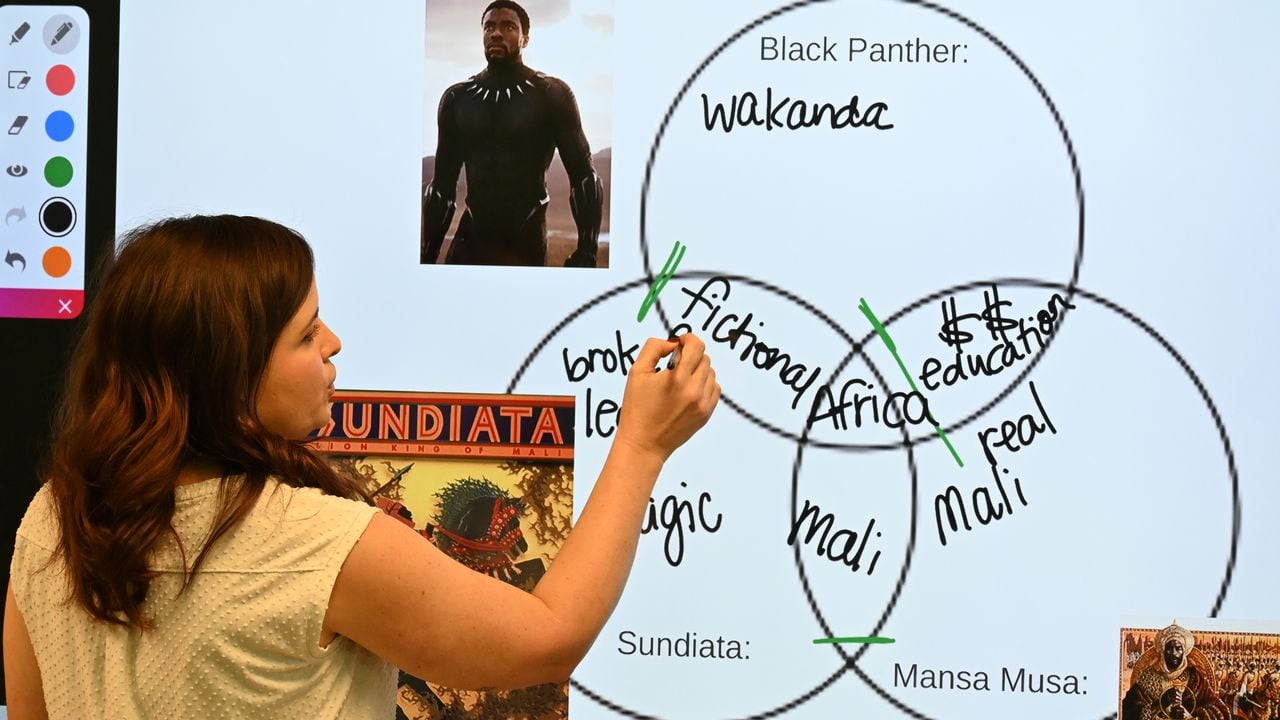

Her students drew connections between Mali emperors Sundiata and Mansa Musa and the fictional Black Panther, and spent days researching Wakanda’s 11 tribes using primary sources.

Knowledge of African history is a key foundation to have, Smith said, before students start learning about topics like the slave trade – even though she’s used Black Panther to illustrate those lessons as well.

In a freshman class, she used the film to teach about themes like resistance and the effects of African colonization.

“Often people think of Black History as starting with slavery, but being able to share the vibrant and beautiful cultures and lives of African tribes throughout history helps create a better understanding of the cultural heritage that Black people in America carry with them,” she said.

Smith later taught a sociology course at Murphy High School in Mobile, where she asked students to analyze the role of the movies’ female fighters. She introduced characters like T’Challa and Killmonger to highlight how an individual’s background can impact their behavior.

She even brought in other Marvel films to help students make connections to significant moments in African American history.

In one lesson, she brought up Captain America’s “Super Soldier” studies to talk about medical racism and the Tuskegee syphilis studies. She’s also used Batman to look at social stratification and crime theories.

“There’s a lot of heavy topics in sociology,” she said. “So I found that students are more comfortable to explore those ideas if it’s in a fictional world.”

Eventually, Smith realized she could broaden her course. She worked with Travis Langley, a professor at Henderson State University and “superherologist,” to dig deeper into fandom psychology. That year, she pitched a full course on “superhero sociology” to the high school principal.

Over the years, Smith said, some students have had some major breakthroughs in the course and have come out of it with a greater understanding of their own identity and culture. Others have vastly sharpened their writing skills. Some now joke that she’s “ruined movies” for them.

Since the 2022-23 school year, Smith has been teaching a superhero course at Spanish Fort High School in Baldwin County. She plans to incorporate the new sequel, “Wakanda Forever,” into lessons on Haitian and Latin American revolutions.

The school’s principal, Shannon Smith, said she interviewed Krystle on the spot after hearing about her course at a job fair. And she’s already noticing the impact Smith has had on the school.

Students who have never expressed an interest in history before are excited about the subject now, she said, and some are even researching topics on their own.

“It just speaks volumes about Krystle Smith and her ability to relate to teenagers,” she said.

For other movie-loving educators out there, Smith recommends reading “The Dark Fantastic,” which goes through several fictional fandoms and breaks down how different characters relate to history.

And the role of primary sources in helping students understand history can’t be understated, said Smith, who often works together with teachers at her school to identify resources.

One teacher, she noted, used letters from the National Archives to talk about the experiences of African American soldiers overseas. The team is also looking forward to being able to use oral histories from the Africatown archives to help students connect local history to themes like families and relationships.

“Even pulling in little bits here and there,” she said, can make a difference.