Mental health groups’ poll shows support for funding, services

Leigh Few can attest to the dire consequences of missing out on mental health care and the life-saving value of that care when it is found.

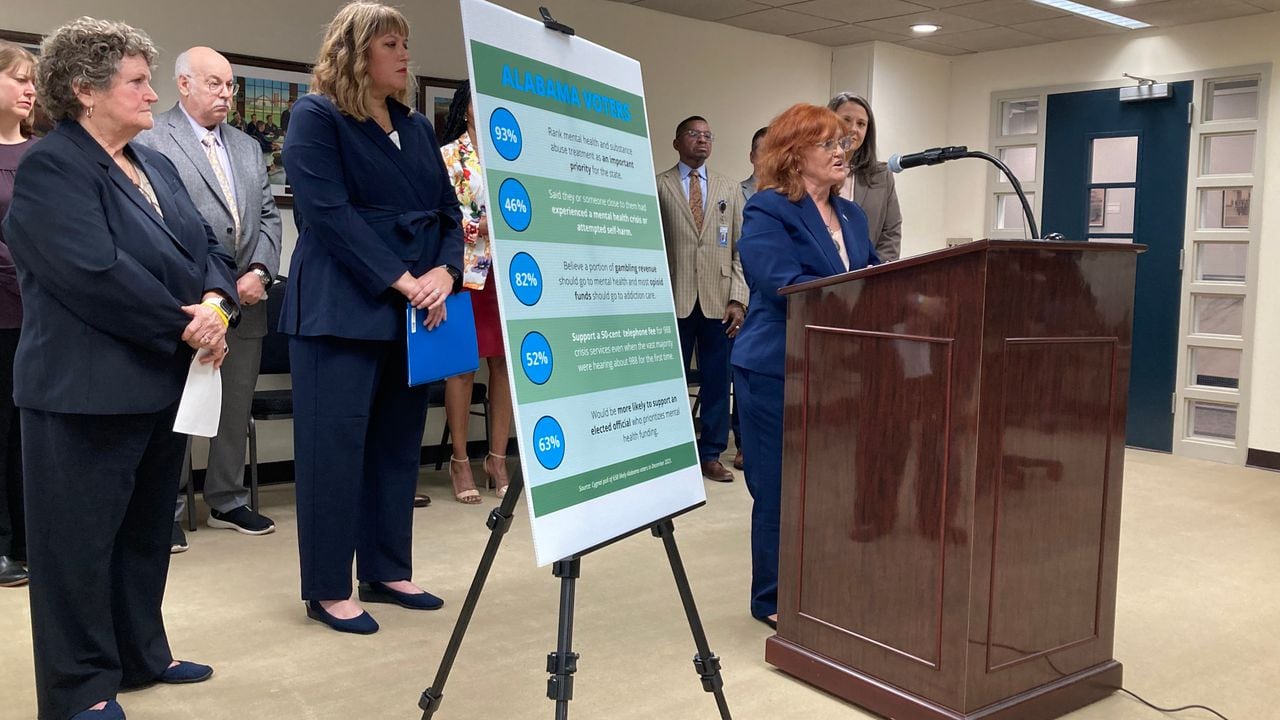

Few, a Walker County native, spoke at a news conference Wednesday to announce the results of a poll showing 93% of Alabamians rank mental health care as a high priority. Forty-six percent of respondents said they or someone close to them had experienced a mental health crisis or attempted self-harm.

The news conference comes two weeks before the start of Alabama’s annual legislative session, when proposals are expected to provide more funds for 988 crisis line call centers and related services, to address a workforce shortage in community mental health centers, and to provide more long-term beds for people involuntarily committed because of mental illnesses.

Few said she was a University of Montevallo graduate who married her high school sweetheart, had three children, and was helping to run a family business, all part of what sounded like a “happy, normal life.”

“I started having trouble completing things, just simple, everyday things,” Few said. “Part of my job was doing our invoices. And I would have them completed and filled out, in the envelopes, and just the thought of going to the mailbox was completely overwhelming.

“And I did not know what was going on. It took everything I had to cook for my children, to wash dishes, just simple things I had done a thousand times became so hard.”

Few sought help but was led to blame herself or believe she just needed to try harder.

“I went to doctors and was told I needed to get some exercise,” Few said. “This was someone who was sleeping most of the day. Was told I needed more sleep. That did not seem realistic. And was actually told, ‘You need to just get up and do it. It’s not really that hard.’ It was that hard. And I couldn’t just get up and do it.”

Few said she reached the point where she did not want to get out of bed and take a shower.

“I started thinking that I was a failure at life, at our business, and most importantly, at being a mom,” Few said. “So, I started thinking my family would be so much better off without me. And once those thoughts took hold they did not go away and they got worse.”

Those thoughts turned to plans for self-harm, Few said. She did not go into details but indicated things could have ended in tragedy. Instead, Few said an encounter with a deputy sheriff who took time to talk to her put her on the path to recovery.

“He took me to the local ER and stayed with me and insisted that they get me evaluated for the behavioral medicine unit,” Few said. “From there, I was diagnosed with major depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

“A lot of people say when they got their diagnosis that was like the worst day of their lives. For me it was one of the best because now, there was a name for what I had. I knew what it was, which meant we could start working on it.”

Few said she started on medication and treatment five days a week at a community mental health center. She said she was not enthusiastic about it at first but that changed.

“It dawned on me one day that I was actually looking forward to getting up, and getting that shower, and getting dressed, and going into the center because all of a sudden I had a purpose in life,” Few said. “And I had been missing that. And I felt happy and productive.”

As her recovery progressed, she was asked to help other people in the program, first on a part-time basis, then full-time, and eventually as coordinator of the program where she had found help.

Alabama has made progress toward filling the gaps in mental health services, with new crisis centers operating in Huntsville, Tuscaloosa, Birmingham, Montgomery, and Mobile, and more planned as part of a Crisis System of Care.

Alabama’s 988 suicide and crisis line call centers, part of a program established by Congress in 2020, received 53,000 calls during its first year of operation in 2022-2023, according to a press release that accompanied the release of the poll results.

Holly McCorkle of the Alabama Council for Behavioral Healthcare said the state needs to continue to fill gaps in mental health services for those in crisis and those in need of long-term care.

Last year, the Legislature considered, but did not pass, a bill that would have added a 98-cent monthly user fee on cellphone bills to fund the 988 call centers and related services. McCorkle said she is hopeful legislation will be proposed again this year, possibly for a smaller fee of 50 cents. She said that would generate about $30 million a year, enough to fully fund the crisis call centers and provide some mobile crisis response capabilities in every county. Currently, most counties do have have access to a crisis center or mobile crisis outreach teams.

McCorkle talked about the poll, conducted by the polling firm Cygnal in December. It was a survey of 620 Alabama voters on behalf of the Alabama Council for Behavioral Healthcare, the Behavioral Healthcare Alliance of Alabama, and NAMI Alabama, the state chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

The poll showed only 20% of respondents were aware of the 988 crisis line. But when provided some information about it, 52% supported the idea of the 50-cent user fee.

“We believe Alabamians would be even more supportive if they knew the fees would ensure some level of care in all communities,” McCorkle said. “The bottom line is, Alabamians recognize the need for mental health and substance abuse treatment and they clearly think access to care should be a priority for our policy makers, in terms of focus and funding.”

McCorkle said another possible funding source for mental health services is revenue from a gambling proposal that lawmakers might consider this year. Alabama House Republicans are working on a bill but have not announced what’s in it. A bill to allow expanded legal gambling, such as a lottery, casinos and sports betting, would also require approval by voters.

The poll showed more than 82% of respondents supported using funds from Alabama’s share of an opioid settlement on substance abuse treatment.

“Whether it’s the phone fee or some other sources, we are advocating for sustainable funding for 988 crisis services,” McCorkle said. “We’re advocating for the opioid settlement funds to be used primarily for substance abuse treatment and prevention.”

Few said she was encouraged by the poll results. In two months, Few will retire after 20 years with the center where she received help. But she will remain involved in mental health care as a program coordinator for NAMI Alabama.

“I am living proof of what can happen when you get the help that you need as far as mental health is concerned,” Few said. “Because if it was not for that deputy, if it was not for the therapists, it if was not for the mental health center, I don’t think I’d be here today.”