Citizen journalist La Gordiloca makes news almost as often as she breaks it

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

Illustration by Maria Contreras for palabraMaria Contreras for palabra

Traffic had once again ground to a halt on the interstate highway that cuts through the Texas border city of Laredo, and Priscilla Villarreal did what any good reporter would. The social media personality and citizen journalist grabbed her phone and texted a police source, fishing for information.

Villarreal consistently breaks news about day-to-day crime and traffic incidents in the city of 250,000 — almost all Latino. The audience knows her as La Gordiloca, an affectionate nickname that translates to something like “Crazy Chubby Lady.” It’s a moniker she embraces. Her “Lagordiloca News Laredo Tx” Facebook page is often the first with videos from the scene of breaking news.

She communicates with more than 200,000 followers through meandering, expletive-filled Facebook Live streams. They’re mostly in Spanish and peppered with snark and slang particular to the stretch of Texas-Mexico border where she lives. In unfiltered, often rambling videos shot from her phone, Villarreal hypes local businesses, rants about city and county corruption scandals, and occasionally fundraises for charities.

Villarreal makes news almost as often as she breaks it. Her rush to be first has generated some embarrassing errors with wide-reaching consequences — and spawned a subgenre of Laredo Morning Times stories setting the record straight.

Yet, she maintains a loyal following and is quick to note that her audience eclipses established local media outlets like the Morning Times, my former employer.

Priscilla Villarreal, known by her audience as La Gordiloca.Saenz Photography, via The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression

Her popularity “has to do with the way I say things,” Villarreal tells me. “Because my news is raw. I’m not editing anything. No sugarcoating anything. I put it out there.”

She’s been such a thorn in the side of local officials that, by the time she sent texts about the highway traffic jam in 2017, they already had her in their crosshairs. Those texts to her source vaulted her to the front line of a fight over press freedom.

In a lawsuit now before federal appellate judges, Villarreal alleges local officials used the traffic text to retaliate against her and violated her constitutional rights.

The incident that triggered Villareal’s text was the death of an official with a federal law enforcement agency who killed himself by jumping off a highway overpass. It was the kind of story traditional U.S. media outlets would approach with caution, likely omitting the very details she sought. But Villarreal, who stumbled into journalism with a heart-rending video of police and paramedics trying to save two child homicide victims, quickly went live with the official’s name and employer.

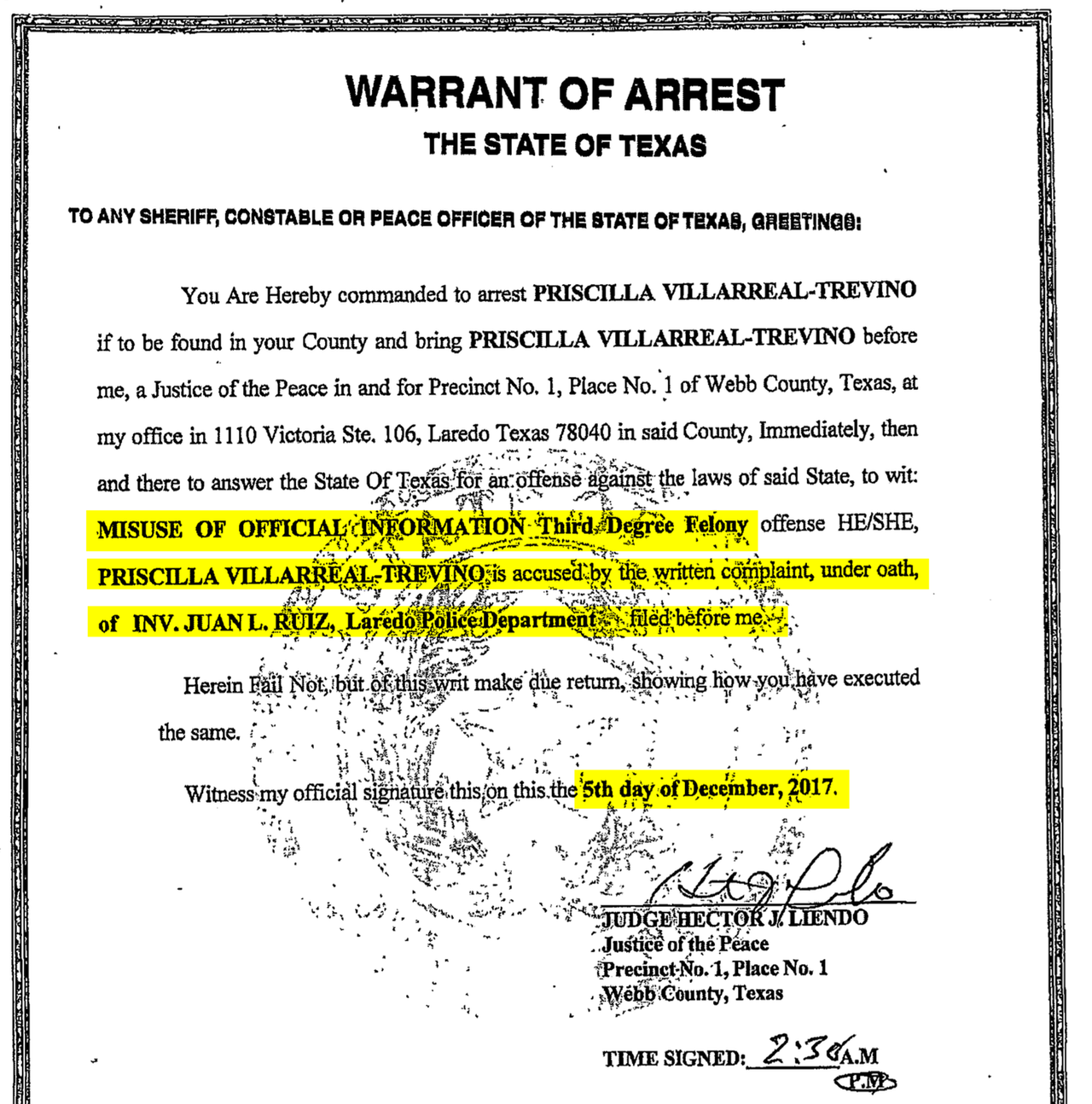

About eight months later, Villarreal received another tip, this time about herself. Laredo police officers had obtained a warrant for her arrest on charges of misuse of official information, a misdemeanor in Texas. It’s a crime when someone “solicits or receives from a public servant information that: the public servant has access to by means of his office or employment; and has not been made public” and does so “with intent to obtain a benefit,” according to the state penal code. The statute defines that information as “information to which the public does not generally have access, and that is prohibited from disclosure under” Texas’ freedom of information laws.

Legal experts have said the statute seems written in a way to criminalize the leaking of information that could help rig bids for government contracts or aid insider trading, but it was now being used to arrest a journalist.

By breaking news with the name she’d obtained through backchannels, Villarreal “gained her popularity in Facebook,” which she could monetize, police alleged.

Villarreal turned herself in and was quickly released from jail on a $30,000 bond. A few months later, in a decision that applies only in Texas’ Webb County, a state district judge ruled that the law against misuse of official information is unconstitutionally vague and threw out the charges against Villarreal. But the judge also found that the Texas statute does not violate the First Amendment.

In 2019, Villarreal sued city and county officials who she said orchestrated the arrest in order to intimidate and silence her in violation of her constitutional rights. She filed her lawsuit in a federal district court, where a judge ruled against her. Ever since Villareal’s ongoing appeal has been gathering interest at a time when police elsewhere have stepped up intimidation tactics aimed at critics and journalists.

Her challenge is now in the hands of the conservative Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals based in New Orleans.

There, Villarreal appears to have found allies among judicial appointees of former President Donald Trump, who in court have staked out traditionally libertarian positions on free speech.

But other veteran court conservatives have signaled they want to shield the officers from her lawsuit and may rule that her arrest was unconstitutional after all.

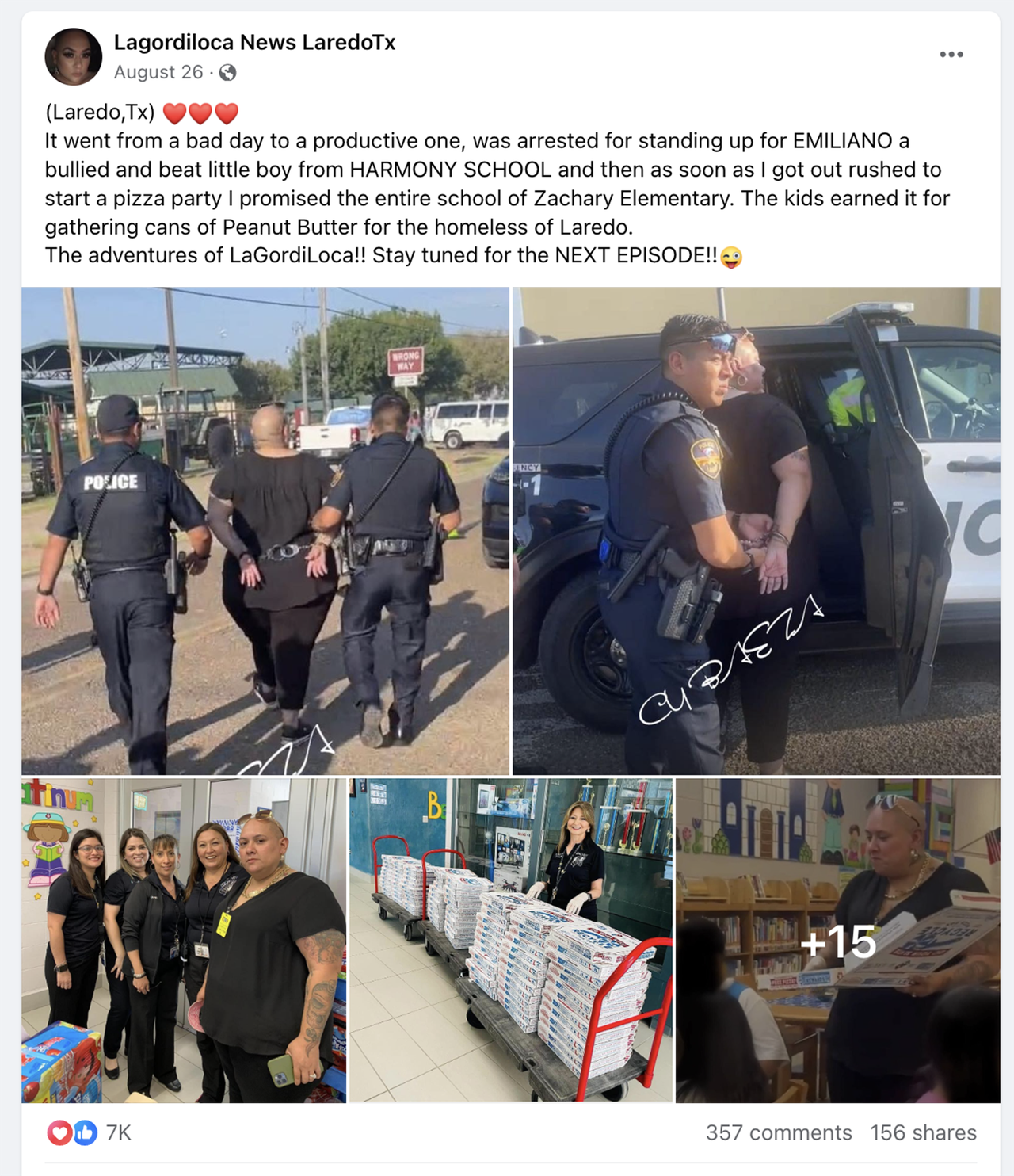

Facebook post by Villarreal being arrested for trespassing after leading a rowdy protest over an alleged bullying incident at a charter school.Priscilla Villarreal, via Facebook

Free speech and strange bedfellows

Villarreal says she wasn’t setting out to change free speech case law when she decided to sue.

“I had so many people messaging me and telling me, ‘You basically need to sue the city and the police department and these individuals as a whole, because what they did to you is not right,’” Villareal told me.

She’s represented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a libertarian free-speech organization. Traditional press freedom groups have also lined up behind her. (Disclosure: palabra.’s sponsor, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, has signed on to an amicus brief supporting Villarreal).

Journalists have always published scoops obtained through police sources and other backchannels. But mainstream news organizations haven’t always acknowledged how similar the reporting tactics of independent firebrands like Villarreal are to those of traditional journalists.

“The fact that Villarreal presents and distributes the information she gathers in a nontraditional way does not deprive her of the full benefit of the First Amendment,” wrote lawyers for a coalition that included the Texas Press Association, the Texas Association of Broadcasters, and the Society of Professional Journalists in a friend of the court (amicus) brief in support of her appeal. Allowing “police to make … arrests for seeking and publishing information from government sources will chill newsgathering across the field of reporting, no matter the platform.”

An even stranger bedfellow is conservative provocateur James O’Keefe of the controversial Project Veritas, which specializes in heavily edited “gotcha” video stings targeting politicians and mainstream journalists. O’Keefe’s amicus brief was filed by the Christian right-leaning religious liberties public interest firm First Liberty Institute.

“No one is going to arrest a New York Times reporter and survive his own cancellation,” First Liberty lawyers wrote on behalf of O’Keefe. “But for journalists who investigate other journalists, powerful political operatives, and high-ranking government officials, a ruling in this case condoning the defendants’ actions will declare an open season against the Davids, like Project Veritas, who take on the Goliaths.”

What’s brought these disparate organizations together is Villarreal’s allegation that prosecutors and police in Webb County and the City of Laredo dredged up an obscure law to punish her for overall coverage and criticism of local government.

Priscilla Villarreal’s mugshot taken after her arrest in 2017.Laredo Police Department

In her complaint, she argues that officials are frustrated that she once recorded an incident of alleged police misconduct and accused the district attorney’s office of giving preferential treatment to an official’s family members in another case.

She argues in her lawsuit that her arrest was part of a longer “pattern of harassment, intimidation, and indifference” by city and county officials.

Some of what she complains about in her lawsuit are tactics police often use against reporters: keeping them a distance from crime scenes, threatening to confiscate equipment, and withholding information they’ve shared with rival outlets. Other allegations are more personal. She says Laredo police refused to take her seriously when she reported being the victim of a crime. She also alleges that city officials tried to obstruct the placement of a reading kiosk named after her late niece in a municipal park.

When she was arrested in December 2017, Villarreal alleges in her lawsuit, police officers and city employees gathered to record the booking on their phones, mocking her practice of recording them at crime scenes.

“Defendants did so with the intent that it dissuade Villarreal from engaging in further journalism efforts,” the lawsuit alleges.

Villarreal alleges her constitutional rights to free speech and protection from unreasonable search and seizure were violated. She’s asking for damages.

But first, she must convince federal courts that the local officials don’t deserve qualified immunity, a protection created by the U.S. Supreme Court that stops most lawsuits against government officials. She needs to prove the officials knew, or should have known, they were violating her rights when they arrested her.

In most cases, plaintiffs need to show that the alleged actions of officials violated a statute or the Constitution in a way that is already “clearly established.” That’s been interpreted to mean that an appellate court has previously ruled in other cases that similar, official actions violated someone’s rights.

Villarreal is pursuing another way to overcome qualified immunity: She is attempting to prove it should have been obvious to any reasonable official that texting a police officer to ask for basic information about a newsworthy event was an activity that anyone in the United States has a right to conduct.

“All Americans benefit from the First Amendment protection to ask government officials questions, whether they’re a reporter for the New York Times, a citizen journalist from Laredo, or a concerned mother at a school board meeting. Without that right, we can’t be an informed public,” her attorney JT Morris told me.

Even if she can defeat the Laredo officials’ claim to qualified immunity, Villarreal will have to then prove the facts she alleged in her lawsuit are true by a preponderance of the evidence.

Lawyers representing the city officials have argued that while U.S. Supreme Court precedent may protect publishing leaked information, it doesn’t protect the right to solicit such information. By asking a police officer for the information, rather than waiting for a proactive leak, Villarreal violated Texas law, city officials argue.

“Because there was no clearly established constitutional right to solicit this type of non-public information from a government official to obtain a personal benefit or attempt to harm or defraud another at the time of (Villarreal’s) arrest, the officers retain the shield of qualified immunity,” their lawyers wrote in a court filing.

Civil libertarians on both ends of the political spectrum say qualified immunity is designed to shield government officials from accountability. If it’s granted in Villarreal’s case, the courts would be saying, “If government officials can find a unique way to violate civil rights or launder misconduct through state statute or government ordinance, judges are going to let it slide,” said Jaba Tsitsuashvili, an attorney for the libertarian-leaning public interest law firm the Institute for Justice, which also filed an amicus brief on Villarreal’s behalf.

Illustration by Maria Contreras for palabraMaria Contreras for palabra

Villarreal’s case is part of a pattern of reports in recent years of police and other public officials using threats, searches, and arrests to intimidate U.S. reporters and critics, according to monitoring groups like the Committee to Protect Journalists.

A spate of high-profile incidents occurred in 2023. In February, the Supreme Court refused to review a ruling that gave qualified immunity to officers who had arrested an Ohio man for a mocking parody on Facebook, ending his lawsuit. A New Hampshire man who was arrested after criticizing his town’s former police chief is also suing. In August, a journalist at the Marion County Record in Kansas filed a lawsuit against police officials who served a search warrant and seized business equipment from the newspaper office, alleging the raid was done to silence reporting. (The 98-year-old newspaper owner’s home was also raided; she died of cardiac arrest a day later.) In October, police in Alabama arrested an editor and publisher for printing leaked information. That same month, officials in a Chicago suburb ticketed a reporter for contacting municipal officials directly, rather than through the city spokesperson.

“I think the implications of (Villarreal’s lawsuit) are huge because this is an evolving question of law,” Tsitsuashvili said. “How is qualified immunity going to apply in the First Amendment context?”

A reporter like no other

The granddaughter of immigrants from Mexico and the daughter of a migrant worker, Villareal grew up in a working-class neighborhood in central Laredo. She’s told reporters she was kicked out of high school at age 15 and had run-ins with the law before she found her niche as a citizen journalist.

Her arrest catapulted her into the national spotlight. She’s been featured in major media outlets, and in 2021, STARZ announced it was developing a TV series based on her life.

“I want to give thanks to the Laredo Police Department for my arrest,” she told the Laredo Morning Times soon after the show was announced. “I want to give thanks to the district attorney’s office for signing that warrant.”

Her larger-than-life persona and gift for creative curses don’t exactly fit the mold of a staid local news broadcaster or of the disheveled nerdy daily newspaper reporter.

“She’s not really what we would consider a trained journalist,” said Celeste González de Bustamante, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Journalism and Media who has studied reporting on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. “She doesn’t need a degree from a journalism school, nor does anyone need a journalism degree to produce good journalism.”

Villarreal’s Spanish broadcasts, peppered with slang and English, and her sensationalism and fixation on the crime beat, resemble the voyeuristic, tabloid nota roja and policíaca crime beats popular in Mexico. They’re “indicative of media and culture of the border,” González said. “There are influences on both sides that go both ways, and it’s its own hybrid culture. And Laredo is distinct from the culture that exists in Tijuana and ambos Nogales.”

“I guess it’s a reflection of … traditional media outlets and sometimes their inability to connect with various people in different communities,” González added. “(Villarreal) has a certain amount of authenticity for her followers that they don’t see in traditional publications. That’s been a difficult thing for news outlets. People don’t see themselves in what’s reported sometimes, so they end up not reading these traditional outlets. And others who aren’t trained (journalists) end up filling the gaps, for better or worse.”

Villarreal has been mired in other controversies. In 2020, she issued a public apology (albeit including her trademark expletives) after she broadcast racist commentary during a video of a Webb County Sheriff’s deputy arresting a Black man. Sitting in her car and using her phone to take video through the window, Villarreal added imagined dialogue between the two using offensive stereotypes. And in 2017, she created a panic by falsely reporting that Laredo was facing a gas shortage. She’s also been known to broadcast unsubstantiated allegations about government officials. In 2016, a judge ordered her to pay nearly $300,000 to a daycare that had alleged she had defamed the company as part of a default judgment issued after Villarreal failed to appear.

Along the way, she’s also leapt across the line between journalism and advocacy, picking sides in political contests and publicly mulling running for public office. In August, she was arrested for trespassing after leading a rowdy protest over an alleged bullying incident at a charter school.

Villarreal’s arrest warrant, issued in December 2017, for misuse of official information.Webb County Courthouse, Texas 111th Judicial District

“It’s part street theater and it’s part truth-telling,” said María Eugenia “Meg” Guerra, a longtime Laredo journalist who publishes LareDOS[redux], the digital heir to an alternative print publication she ran for 20 years. “There’s so much excitement and drama in some of the stuff she does, you just can’t call it straight journalism.”

Ethical breaches aren’t crimes, however, said Daxton “Chip” Stewart, an assistant provost and media law professor at Texas Christian University. Journalists who commit libel can face civil lawsuits, and those who don’t adhere to ethical standards can face repercussions in the court of public opinion.

“We don’t want the government to be dictating what good journalism is,” he said. “That’s what the press clause of the First Amendment is all about.”

And despite her penchant for drama, Villarreal is well-sourced, persistent, and has a nose for news, Guerra said.

“Probably, if she studied journalism, she’d be really good at it, because she has the instinct for it,” added Guerra, whose publication also regularly took on local officials in the past. Villarreal’s followers are “probably going to learn something that you might need to know about local government.”

In interviews, Villarreal focuses more on her journalism and less on her advocacy, telling me: “I see myself as a freelance reporter, basically. I have more following than our local newspaper and news station, and that says something.”

No law defines a journalist

While her attorneys argue that anyone can ask a police officer for information about a traffic incident, they’re using Villarreal’s status as a journalist to illustrate just how obvious it should have been to the arresting officers that her actions were protected by the First Amendment. Like other reporters, Villarreal sometimes reaches out to the Laredo Police Department spokesperson. Also like other reporters, sometimes she seeks information from her sources in the department.

The officials involved in her arrest — District Attorney Isidro Alaniz, Marisela Jacaman, his first assistant; and former Police Chief Claudio Treviño Jr. are all defendants — had to know that doing so was protected by the First Amendment, her lawyers argued in Laredo’s federal courthouse.

But U.S. Magistrate Judge John Kazen wasn’t convinced. In 2020, he ruled that the officials involved in Villarreal’s arrest were entitled to qualified immunity. It wasn’t patently obvious to the officers, who had obtained an arrest warrant from a justice of the peace, that arresting her would violate her rights, Kazen wrote in his opinion.

Villarreal’s mugshot taken after her arrest in August 2023.Laredo Police Department

Villarreal’s next step was to ask the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans to overturn Kazen’s decision. The Fifth Circuit, which covers Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, has twice in the last three years been ordered by the Supreme Court to reconsider its refusal to grant qualified immunity to prison guards who tortured inmates. Trump’s appointment of six judges, some of them prominent conservative legal theorists, has only cemented the perception of a politicized court on the front line of culture wars.

The Villarreal case initially drew a three-judge panel of Priscilla Richman, the court’s chief judge and a George W. Bush appointee; James Ho, a former Texas solicitor general and a Trump appointee; and James Graves, an Obama appointee.

Ho and Graves found in 2021 that Villarreal’s First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated in such an obvious manner that Webb County, the City of Laredo, and the various public officials were not entitled to qualified immunity.

“If the First Amendment means anything, it surely means that a citizen journalist has the right to ask a public official a question, without fear of being imprisoned,” Ho wrote in his majority opinion. “Yet that is exactly what happened here: Priscilla Villarreal was put in jail for asking a police officer a question.”

That police can’t retaliate against reporters for basic journalism is such an ingrained aspect of U.S. society that even characters in blockbuster movies know it, Ho argued.

“Indeed,” Ho wrote, “[E]ven Captain Lorenzo, the stubborn police chief in Die Hard 2, acknowledged: ‘Now personally, I’d like to lock every [expletive] reporter out of the airport. But then they’d just pull that ‘freedom of speech’ [expletive] on us and the ACLU would be all over us.’ … Captain Lorenzo understood this. The officers in Laredo should have, too.”

Richman disagreed. The main thrust of her dissenting opinion is that it’s hard to place on the shoulders of law enforcement officers blame for an arrest when a magistrate, an ostensibly impartial bulwark who’s supposed to make police officers prove they have probable cause, had signed off on Villarreal’s arrest warrant. She also argued that there might be times when the Texas law could be used to arrest journalists for publishing information without running afoul of the Constitution.

What is public information?

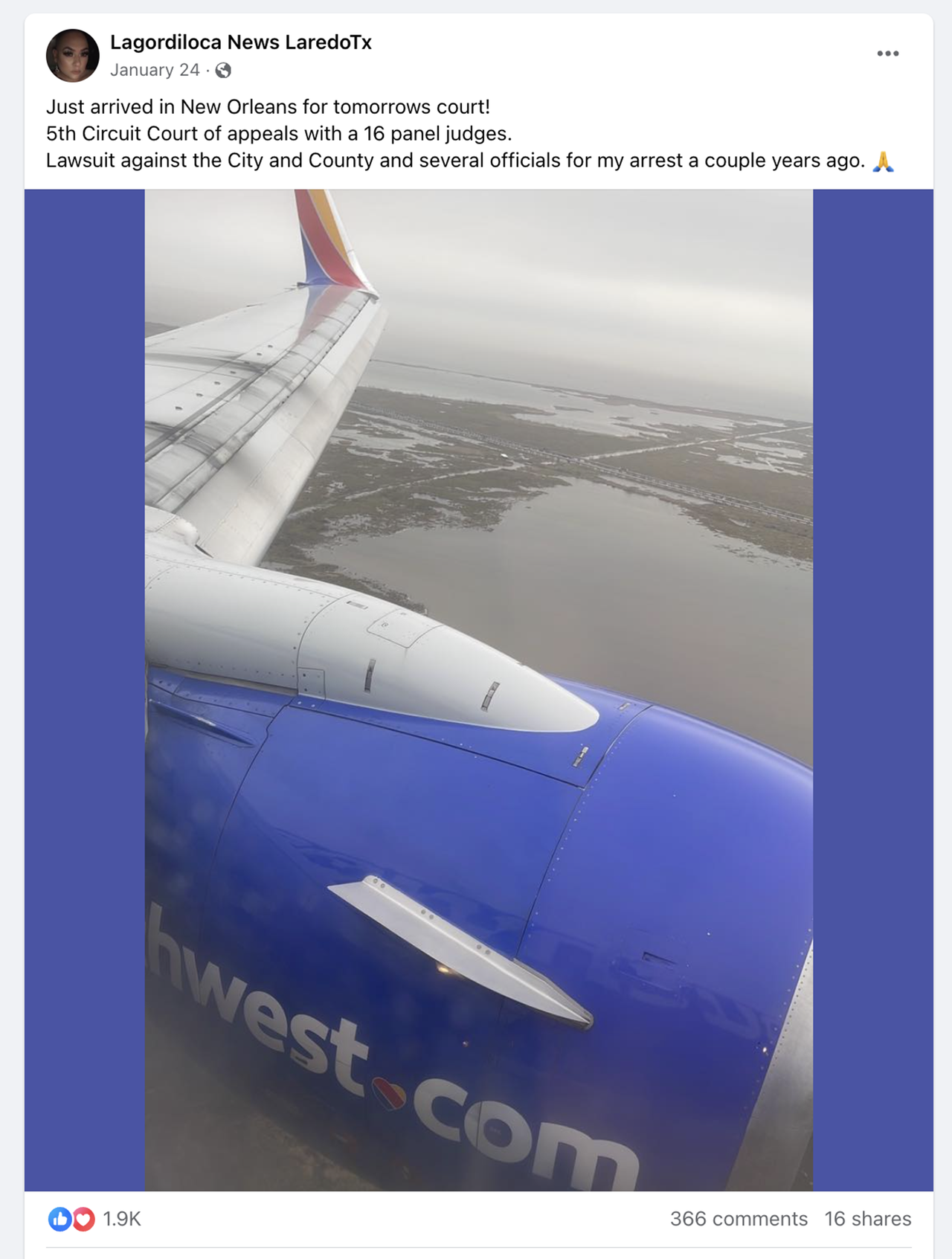

In January, Villarreal boarded a plane to New Orleans. She chronicled the trip on Facebook. Her followers cheered her on in the comments.

The city and county officials had appealed. Instead of going to the Supreme Court, they asked all 16 judges on the Fifth Circuit at the time to overturn Ho’s and Graves’s findings and give them qualified immunity. Villarreal was on hand to watch her lawyers make her case.

Facebook post by Villarreal upon her arrival to New Orleans where the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals received her case.Priscilla Villarreal, via Facebook

In oral arguments, lawyers for the city, county, and state of Texas took the position that while Villarreal had a right to ask questions, she had other avenues to do that, principally through the public information officer or a request under the Texas Public Information Act.

“If you get it from an official source there is an implied representation of lawfulness that is not present here, where Plaintiff deliberately decided to go … outside of official channels to get information that she knew or at least was reckless … as to the knowledge that this information was not legal to be disclosed,” said Lanora Christine Pettit, the principal deputy solicitor general for the Texas attorney general.

Historically, public information laws have had no connection to free speech, Stewart, the TCU professor, said. Most states and communities have laws that dictate the information officials must make public. But those are just means of disseminating information that governmental bodies have voluntarily adopted. Courts have consistently upheld journalists’ rights to seek information through backchannels. Only when journalists induce a government official to break a law can they be held criminally liable, U.S. courts have consistently held. Villarreal’s arrest was particularly absurd, Stewart said, because the information she sought would eventually become public record anyway.

“You have a First Amendment right to speak and publish that has nothing to do with open records or open meetings,” he said. “If the Supreme Court has told us anything, publishing truthful things of public interest is going to get really, really high levels of protection.”

During the arguments in New Orleans, Ho scoffed at the notion that reporters, or anyone in the United States, could be arrested for seeking information outside of official channels.

“She went through the wrong channels?” he asked. “Wrong procedure. So, jail.”

Richman was joined in her skepticism of Villarreal’s arguments by Judge Edith Jones, a Reagan appointee who until the arrival of the Trump judges was considered one of the most far-right jurists in the United States. Jones asked, Don’t the police have a right to withhold the names of victims until they notify family members?

“She could have waited, waited like the rest of the press in Laredo, and obtained it from (the public information officer) a couple hours after the families had been notified,” Jones said.

In the world Jones described, the government has met its obligations under the First Amendment simply by providing reporters with the right to seek information through the media relations office or a public records request. Not only that, but the government can compel reporters to use those avenues with the threat of arrest for seeking the same information faster through their own sources.

Illustration by Maria Contreras for palabraMaria Contreras for palabra

Richman painted a scenario for Morris, Villarreal’s attorney. Suppose someone asked Villarreal to publish the name of a government witness and, to encourage her, offered her reporting equipment. If Villarreal obtained that information from a police source and published it, could the police arrest her?

“That would be protected,” Morris responded.

Jones jumped in.

“So basically, you’re saying that these are dead letters, Freedom of Information, that the whole … idea of government confidentiality is a mirage because anybody can go and solicit information from anybody who is willing to take the risk,” she said. “So basically you’re saying government can’t function.”

The argument being made by Jones and the officials who arrested Villarreal is “really dangerous,” said Tsitsuashvili, the Institute for Justice attorney.

“It says in an era of increasing skepticism of official reports of police misconduct, the government can decide who is and who is not allowed to serve as an information source for public facts, and that is just contrary to our entire tradition,” Tsitsuashvili said. “Ultimately, what they’re arguing is that the criminalization of journalism … is totally fine.”

Almost a year after those oral arguments, the Fifth Circuit hasn’t released an opinion. Recently, a panel comprising Graves, a Reagan appointee, and a Biden appointee stripped qualified immunity from Louisiana sheriff’s deputies who arrested a man for making a joke on Facebook. Even if Richman and Jones have the votes of enough of their court colleagues to throw out the lawsuit, it’s not a given that a majority of the Fifth Circuit judges will endorse their expansive views on the government’s rights to prosecute people who publish information that officials don’t want to be released.

Whatever the outcome, the case will likely be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“This is the kind of thing you could have safely said 10 years ago would have been laughed out of any court in this country,” Stewart said. “All of a sudden, it’s an open question that has First Amendment advocates like me nervous when you have a court one step away from the Supreme Court suggesting jailing a journalist for publishing leaked documents might be OK.”

—

Jason Buch is a freelance reporter based in Texas. He’s spent most of his 15-year career covering the U.S.-Mexico border.

Maria Contreras is an illustrator born and raised in southern Chile. Her illustrations feature loud and saturated colors and are filled with memories. Fear and humor are her two inspirations. Her current clients include The New York Times, The Atlantic, Texas Monthly, Penguin Random House, NPR, The New Yorker, The Telegraph, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, among many other outlets. Her work has been featured in It’s Nice That, Domestika, Wetransfer, Colossal, Creative Boom and other brands. In 2022, she won the Young Guns award from The One Club for Creativity. In 2023, she was an AI42 Selected Winner, was short-listed for WIA2023, served as a judge of Latin American design awards for the D&AD New Blood Portfolio Competition in collaboration with Editor X and was also a judge for the Young Guns award.