Alabama is back in the Rose Bowl. What took so long?

The 2024 Rose Bowl technically takes place on New Year’s Day, but it might seem like Christmas to those with a deep appreciation of college football history.

Alabama makes its triumphant return to Pasadena on Jan. 1, meeting top-ranked Michigan in a game that doubles as a College Football Playoff semifinal. The Crimson Tide not only won a national title the last time it played in that hallowed 101-year-old stadium — a 37-21 victory over Texas in the BCS championship game in 2010 — but a not insignificant portion of the program’s national reputation and prestige was built upon six trips to the Rose Bowl during the first half of the 20th century.

RELATED: Remember the Rose Bowl: Tracing Alabama’s storied football history in Pasadena

Alabama played in the Rose Bowl after the 1925, 1926, 1930, 1934, 1937 and 1945 seasons, winning four of those games and tying another. Four of the Crimson Tide’s 18 claimed national championships came in years that ended in Rose Bowl victories, and the 1945 team finished undefeated, yet un-crowned.

A number of circumstances — some self-inflicted, some unavoidable — have conspired to keep Alabama out of the Rose Bowl game in Pasadena for 78 years. But the Crimson Tide is back, and you can count Alabama native, noted sportswriter and college football historian Ivan Maisel as among those who are extremely happy about that.

“It’s wonderful for anybody with any sense of history,” said Maisel, now semi-retired after more than four decades working for publications such as the Dallas Morning News, Sports Illustrated and ESPN.com. “But if you think about it, Alabama’s last Rose Bowl in Pasadena, you have to be almost 100 years old to have played in it. So there’s really nobody around.

“I think if this had happened 20 or 30 years ago, there would be a much greater ballyhoo about it than there has been now. Because it’s so long ago, nobody really remembers it or understands what that connection was.”

So why has it been so long since Alabama played in a true Rose Bowl game in Pasadena? In short, money, politics and good, old-fashioned stubbornness got in the way.

Alabama end Don Huston, an All-American and future inductee into both the College Football Hall of Fame and Pro Football Hall of Fame was one of the stars of the 1935 Rose Bowl. (AP Photo/Bob Wands)AP

A football game to promote a parade

The first Rose Bowl game — college football’s first postseason game — was played at Pasadena’s Tournament Park in 1902, conceived as a way to help fund the Tournament of Roses Parade on New Year’s Day. Michigan beat Stanford 49-0 that year in a game so lopsided that “Tournament” officials elected to hold events such as chariot races, ostrich races and elephant vs. camel races rather than a football game for the next 13 years.

The Rose Bowl game was restored in 1916, with the State College of Washington (now Washington State) defeating Brown 14-0 to start an annual New Year’s Day tradition. The game moved to the new Rose Bowl stadium in 1923, and Alabama became the first Southern team to play in the Rose Bowl three years later.

In addition to Alabama’s six trips to Pasadena from 1926-46, Georgia Tech (1929), Tulane (1932), Duke (1939 and 1942), Tennessee (1940 and 1945) and Georgia (1943) all played in at least one of the first 32 Rose Bowl games (the 1942 game was held at Duke’s home stadium in Durham, N.C., due to World War II travel restrictions). All told, those Southern teams combined for a 7-6-1 record in the game that would come to be known as the “Granddaddy of Them All.”

Teams such as USC, Stanford, Washington, Washington State, Oregon and California — who would form the backbone of the conference that would later become the Pac-8 (then the Pac-10 and finally the Pac-12) — served as the regular “host” school for the Rose Bowl game. The Midwest-based Big Nine (now the Big Ten), stopped sending teams to Pasadena after Ohio State lost 28-0 to Cal in the 1921 game, citing concerns that the season was already too long and was having a deleterious effect on academics.

“Things were quite different back then,” said Kent Stephens, historian with the College Football Hall of Fame. “University presidents really didn’t like the idea of postseason play. They thought that having their students participate in football and traveling thousands of miles to play a college football game kind of sullied the academic reputation of the school. And so they really weren’t wild about having these games. A lot of schools, once you get into the 1920s, did not participate in bowl games at all. Army, Navy, Notre Dame, the Ivy League teams, the Big Ten teams, they did not wish to participate in postseason play.”

The Big Nine (which became the Big Ten when Michigan State joined in 1949), got a new commissioner in 1945 in Kenneth “Tug” Wilson, a former Northwestern athletics director who began advocating for his conference to return to the Rose Bowl in the post-war years.

Rose Bowl officials were receptive, Stephens said, in part because of tourism. People in midwestern states such as Illinois, Ohio and Michigan — where the Big Ten schools were located — were generally more affluent than their Southern counterparts.

“They thought the people in the Midwest had more money to spend than the people in the South,” Stephens said. “And they might actually agree to come and buy property out there and travel more. And so they were desirous of having the Big Nine/Big Ten teams come to Pasadena. So in the 1930s, they began wooing the Big Nine, but they turned them down.”

In addition, television was coming into its own in the late 1940s. The Midwestern states had a much larger collective population than the Deep South, and thus many more eyeballs to watch televised events such as the Rose Bowl.

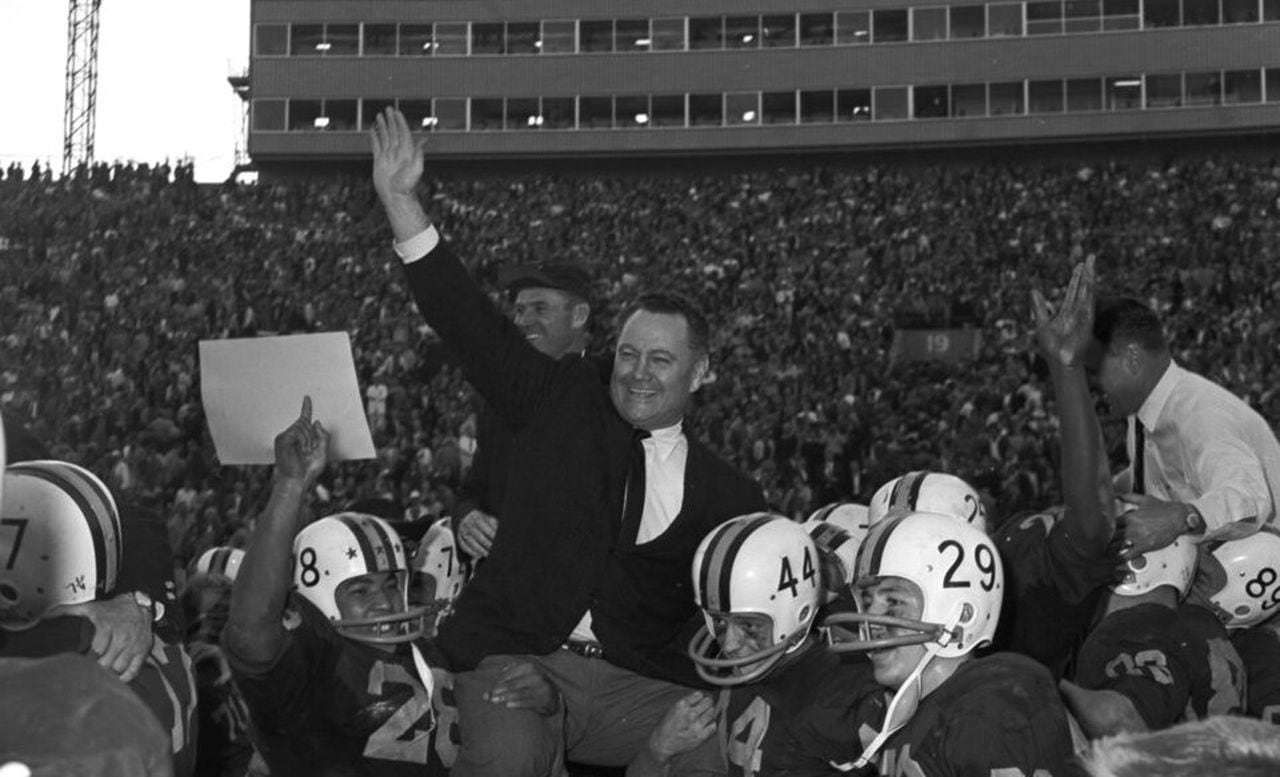

Minnesota coach Murray Warmath is carried off the field by his players after beating UCLA 21-3 in the 1962 Rose Bowl. From 1947-2001, the Rose Bowl exclusively paired teams from the conferences that would eventually be known as the Big Ten and Pac-12. (AP Photo/File)AP

Southern schools get shut out

Early in the 1946 season, Rose Bowl officials proposed a five-year exclusive deal with the Big Nine and the Pacific Coast Conference, the progenitor of the Pac-8/Pac-10/Pac-12. The Big Nine voted “no,” and it appeared for a while as if unbeaten Army — which then featured two Heisman Trophy winners in halfback Glenn Davis and fullback Felix “Doc” Blanchard — would be the “Eastern” representative in the Rose Bowl.

A second vote was held in November and this time the Big Nine agreed to send its champion to the Rose Bowl every year beginning with the Jan. 1, 1947, game.

Illinois beat UCLA 45-14 in that game, the first of 55 consecutive Rose Bowls matching the champions of those two conferences. Alabama, the SEC and the rest of the country was shut out.

“The people in the South, they really thought they were being slapped in the face by the fact that the Rose Bowl sealed this deal with the Big Ten,” Stephens said.

Sportswriters also were outraged. Birmingham News sports editor Zipp Newman accused the Pacific Coast Conference and Big Nine of “selling the Rose Bowl down the river.”

Los Angeles Times sports editor Paul Zimmerman — who later achieved great acclaim covering pro football for Sports Illustrated — headed his column “In Memoriam — The Rose Bowl — Born Jan. 1, 1916. Died Nov. 20, 1946.”

With the agreement in place, however, that was mostly that for more than 50 years.

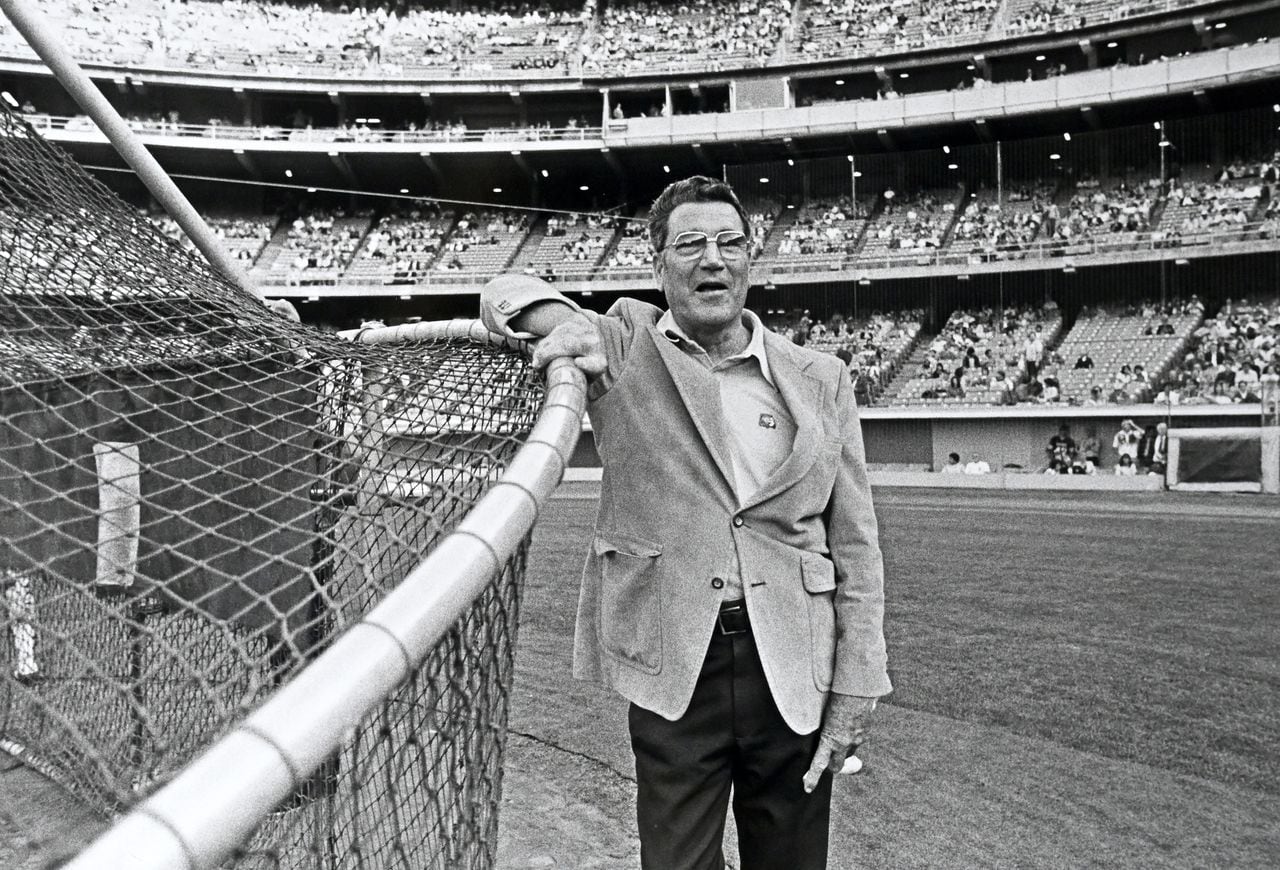

Longtime Los Angeles Times sports writer and columnist Jim Murray, shown here at Dodger Stadium in 1981, was not afraid to ridicule Alabama for failing to integrate its football team after many other schools had done so by the 1960s. (Photo by Jayne Kamin-Oncea/Getty Images)Getty Images

Alabama’s great sin got in the way in 1961

For a time late in the 1961 season, it appeared Alabama might be headed back to the Rose Bowl. Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant had played in the 1935 game as a member of the Crimson Tide, and very much wanted to take his top-ranked, undefeated team to Pasadena.

The opening for Alabama was created because Ohio State’s faculty senate remained opposed to the idea of sending the third-ranked Buckeyes to the Rose Bowl, or any postseason game. Minnesota was another possibility, but the Gophers had played in the previous January’s Rose Bowl, and the Big Ten typically tried to avoid sending the same team to Pasadena two years in a row.

The Pacific Coast Conference had broken up by 1961, leaving in its place the five-team Athletic Association of Western Universities. The league included UCLA, USC, Washington, Stanford and California, and it was the Bruins who were extended the Rose Bowl bid that year.

Newspaper reports in both the South and on the West Coast indicated a UCLA-Alabama matchup in the Rose Bowl appeared likely. It appeared to be so much of a fait accompli that the Los Angeles Times sent columnist Jim Murray to cover Alabama’s late-season games vs. Georgia Tech and Auburn.

On Nov. 14, Rube Samuelsen wrote in the Pasadena Independent that Alabama playing in the Rose Bowl was “actually nearer probability than possibility.” Alabama could not officially accept a bowl bid until after its regular-season finale vs. Auburn on Dec. 2, and the New Orleans-based Sugar Bowl was of course also highly interested in Bryant’s first great Crimson Tide team.

“The Big Ten was dragging its feet, making a deal with the Rose Bowl,” Maisel said. “And Bryant thought he could get the ‘61 team into the game. But then Jim Murray started writing columns.”

As strong as the 1961 Alabama football team was, the state’s hostile reaction to the Civil Rights Movement had begun to draw negative national attention by that year. On May 14, white supremacists firebombed one Freedom Riders bus near Anniston and brutally beat a second group of riders when they arrived at the Birmingham Trailways bus station.

Alabama’s roster, like every team in the SEC (along with the ACC and Southwest Conference) at the time, was all white. Like many of the programs on the West Coast and in the Midwest, UCLA’s teams had been integrated for more than 20 years.

The Crimson Tide had played an integrated team in the postseason two years before, losing 7-0 to Penn State in the Liberty Bowl in Philadelphia at the end of the 1959 season. But on Nov. 17, 1961, UCLA’s student newspaper reported that several Black players on the Bruins’ team — as well as a number of African-American students who planned to attend the game as fans — were threatening to boycott the Rose Bowl should Alabama be invited to Pasadena.

Murray seized on this storyline during his trip to Alabama, asking Bryant directly following the Georgia Tech game if he had any reaction to the threat of a boycott. According to Murray’s Nov. 20 L.A. Times column, Bryant responded “I would have nothing to say about that. Neither will the university, I am sure.”

Murray lampooned Southern states’ insistence on continuing to segregate their college sports teams (as well as their public facilities) in the same column, which carried the provocative headline “Bedsheets and ‘Bama.” He noted that Alabama’s white supremacist politicians had “cowed and terrified their own people,” including those who would decide where the football team would play its bowl game.

Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant is shown on the sideline with quarterback Pat Trammell (10) during the Jan. 1, 1962, Sugar Bowl vs. Arkansas at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans. The Crimson Tide played in the Sugar Bowl after first being considered for a berth in the Rose Bowl. (Birmingham Post-Herald file photo)ph

Whether because of UCLA’s threatened boycott, Murray’s reporting or some other reason, momentum for Alabama playing in the Rose Bowl fizzled in short order. On Nov. 25, Alabama’s players voted to accept an offer to play Arkansas in the Sugar Bowl if one were extended, and the Rose Bowl ended up matching Minnesota with UCLA.

Bryant later wrote in his 1975 autobiography “Bear,” that the issue was moot because Rose Bowl never actually invited Alabama to the 1962 Rose Bowl. He certainly blamed Murray for the snub.

“Jim Murray came over and saw us play and made a fuss over our being considered for the Rose Bowl when we won then national championship in 1961,” Bryant said. “He wrote about segregation and the Alabama Ku Klux Klan and every unrelated scandalous thing he could think of, and we didn’t get the invitation.”

Alabama was voted No. 1 in the Associated Press poll after beating Auburn 34-0 in its regular-season finale, then beat Arkansas 10-3 in the Sugar Bowl to finish 11-0. The Crimson Tide began to recruit black players in 1970, and would play and win its first game with an integrated squad the following year vs. USC, albeit at the Los Angeles Coliseum instead of the Rose Bowl.

Murray continued to criticize Alabama’s failure to integrate throughout the 1960s. It’s widely believed he played a major role in the Crimson Tide being denied a third straight national championship despite an unbeaten team in 1966, ridiculing that year’s still all-white team as the “magnolia champions” rather than a true title contender.

Alabama linebacker Rolando McClain (25), offensive lineman Mike Johnson (78), running back Mark Ingram (22), defensive lineman Marcell Dareus (57) and defensive back Javier Arenas (28) hold the BCS National Championship trophy after defeating Texas 37-21 at The Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif., Thursday, Jan. 7, 2009. (Press-Register file photo by Bill Starling)BN

The Rose Bowl blockade finally breaks

By the 1970s, other bowl games had followed the Rose Bowl’s lead in agreeing to exclusive deals with other conferences. The Cotton Bowl, formed in 1937, was locked in with the Southwest Conference nearly from the beginning.

The Orange Bowl, first played Jan. 1, 1935, began inviting the Big 8 champion to Miami most years beginning in the mid-1950s. The Sugar Bowl (which also debuted in 1935) more often than not included a Southeastern Conference team, and offered an automatic bid to that league’s champion beginning in 1975.

The Rose Bowl’s deal with the Pac-10 and Big Ten led to a number of split national championships, notably in 1991 (Washington and Miami), 1997 (Michigan and Nebraska) and 2003 (USC and LSU). It wasn’t until the Bowl Championship Series secured the Rose Bowl’s participation that a team outside the Big Ten or Pac-10 (later Pac-12) would again play in the actual Rose Bowl game.

Miami and Nebraska met for the national championship in the 2002 Rose Bowl, and Oklahoma and Texas also played in the postseason in Pasadena in the first decade of the 21st century. The BCS went to a “Plus-1″ system with a separate championship game in 2006, meaning the Rose Bowl went back to a Big Ten/Pac-12 affair until the College Football Playoff came into being in 2014.

Alabama in 2010 and Auburn in 2014 both played in the BCS title game in Pasadena, with the Crimson Tide beating Texas and the Tigers falling to Florida State. But an SEC team would not actually play in the Rose Bowl game until the 2016 season.

Georgia beat Oklahoma 54-48 in overtime in the 2017 Rose Bowl, which was a CFP semifinal. The Bulldogs were the first SEC team since that 1945 Alabama squad to play in the Rose Bowl game.

Four years later, the Rose Bowl was again a CFP semifinal, and again featured an SEC team. But California state restrictions in place during the COVID pandemic forced the Jan. 1, 2021, game to be moved to Arlington, Texas, where Alabama beat Notre Dame 31-14 to advance to the championship game.

And so it is now that Alabama finally returns to Pasadena for the Rose Bowl game. Crimson Tide coach Nick Saban coached in the 1988 Rose Bowl as a Michigan State assistant before leading his Alabama team to Pasadena for the BCS title game after the 2009 season.

“We’re very excited about being able to play in the College Football Playoff, very excited about playing in the Rose Bowl,” Saban said on Dec. 3. “My experience in the Big Ten is we always referred to it as the ‘Granddaddy of Them All.’ We played there in 2009, and it was a wonderful experience, a lot of great people and first-class organization in every way.”

Creg Stephenson has worked for AL.com since 2010 and has covered college football for a variety of publications since 1994. Contact him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter at @CregStephenson.