Don’t think guaranteed income is fair? This Birmingham mom might change your mind

This is an opinion column.

Miyah Ford aspires to be a surgeon.

Growing up in the northeast Birmingham neighborhood called Center Point, she wanted to be a teacher. As she grew older, she was drawn to medicine, to becoming a pediatrician, specifically — until watching “Grey’s Anatomy,” the long-running, multilayered Shonda Rhimes television series, shifted her dream. “That got me thinking about surgeons,” Ford says. “I haven’t decided on a neurosurgeon or cardiovascular surgeon, but that’s my ultimate goal.”

Life has a way of messin’ with dreams — messin’ with them like those trilflin’ slap-happy cats in videos that invade my timeline.

It’s messed with all of us. It messed with Ford.

She’s 25 now, a single mother with three children: a 4-year-old son, and two daughters — one will be 2 next month, and the other is 4 months old.

She was in nursing school a few years back, a small side-step toward the dream, when she became pregnant with her son. The pregnancy “took a toll on me,” Ford says, and caused her to drop out. Last year she was working at Children’s Hospital of Alabama when complications from the latest pregnancy created workplace restrictions Children’s could not accommodate. So just as she’d moved into a new apartment, she lost her job.

Though not her dreams. She hopes to re-enroll in nursing school. “When my kids get a little bit older and it’s not hard for somebody to watch them,” she says. “I don’t trust a lot of people to watch them because there’s so much going on in the world. Normally my grandmother watches them. My mom — me and her got pregnant around the same time so when I had my daughter, she had my little sister. That kind of took her off the list of people able to watch them.”

The concept of ”guaranteed income” — a monthly no-strings, unrestricted cash payment given to individuals — needs a bit of a rebrand. Who wouldn’t want a bit of extra cash every month? Unstrung cash. The concept has been around for a few years now and tried in a few cities. Supporters believe a preponderance of Americans is living on the economic edge. They’re working — or trying. Though maybe they can’t afford childcare. Or they lack reliable transportation.

Or perhaps the stress of stretching every month is simply too strenuous.

The few extra dollars pull them from the brink. They’ll use them wisely, to fill a necessary need. A need that pumps the money back into the economy. Or eliminates debt. Or builds a nest for the future.

There are critics, of course. There always are when new, maybe radical ideas are on the table. Outside-the-box ideas. Guaranteed-income haters view it as an undeserved handout that would douse the recipient’s desire to work and be squandered on unneeded luxuries rather than to fund real needs.

That’s not the case. Not even close, according to the Chicago-based Shriver Center on Poverty Law. “Participants in these programs,” it reported last year, “are using funds in ways that benefit their families’ long-term economic health — by paying for rent in a better school district, taking a community college course to improve job skills, saving to cover the expenses of starting a small business, or eliminating old debts that would otherwise trap a family in perpetual poverty.”

It’s certainly not the case with Miyah Ford.

She was among 110 single mothers in Birmingham who began receiving $375 monthly last March through Embrace Mothers, a guaranteed-income pilot program launched in Birmingham in partnership with Mayors for Guaranteed Income (MGI) and funded with a $500,000 foundation grant. The final payment, delivered via debit card, comes in February.

“Three out of four families in Alabama have a female breadwinner,” says Women’s Foundation of Alabama President/CEO Melanie Bridgeforth. “Yet women — the very backbone of our communities — are the most likely to be underemployed, underpaid, and lacking adequate work supports such as childcare, paid leave, and healthcare. These realities are especially harsh for single mothers, who make up 60% of Birmingham’s population.”

Ford’s initial plan was to save the money, maybe spending some on children’s clothes. She’d just gotten the Children’s gig and moved into a new apartment. Her salary covered most expenses. “I could put the [$375] towards their future funding,” she says.

Life has a way, alas. Yes, it does.

Not long after the payments began, Ford learned she was pregnant. There were no issues with her first pregnancies, but she says being on her feet at work sparked the complications. “The hard, concrete floors bothered me to the point my feet were swelling,” she recalls. “Then my hands were swelling, and I couldn’t breathe a lot of days. Then, my son’s growth kind of stopped. My doctors are more concerned about why his growth stopped and they didn’t want me to do anything extraneous to cause more complications. Because I lost my job, the money ultimately became what I relied on for handling everything.

“I had just gotten the apartment, and literally just put down my deposit, which was pretty much half of my last check.”

That’s the economic edge, the precipice from which many fall. Into homeless. Into desperation. Into a deep pit of dependency.

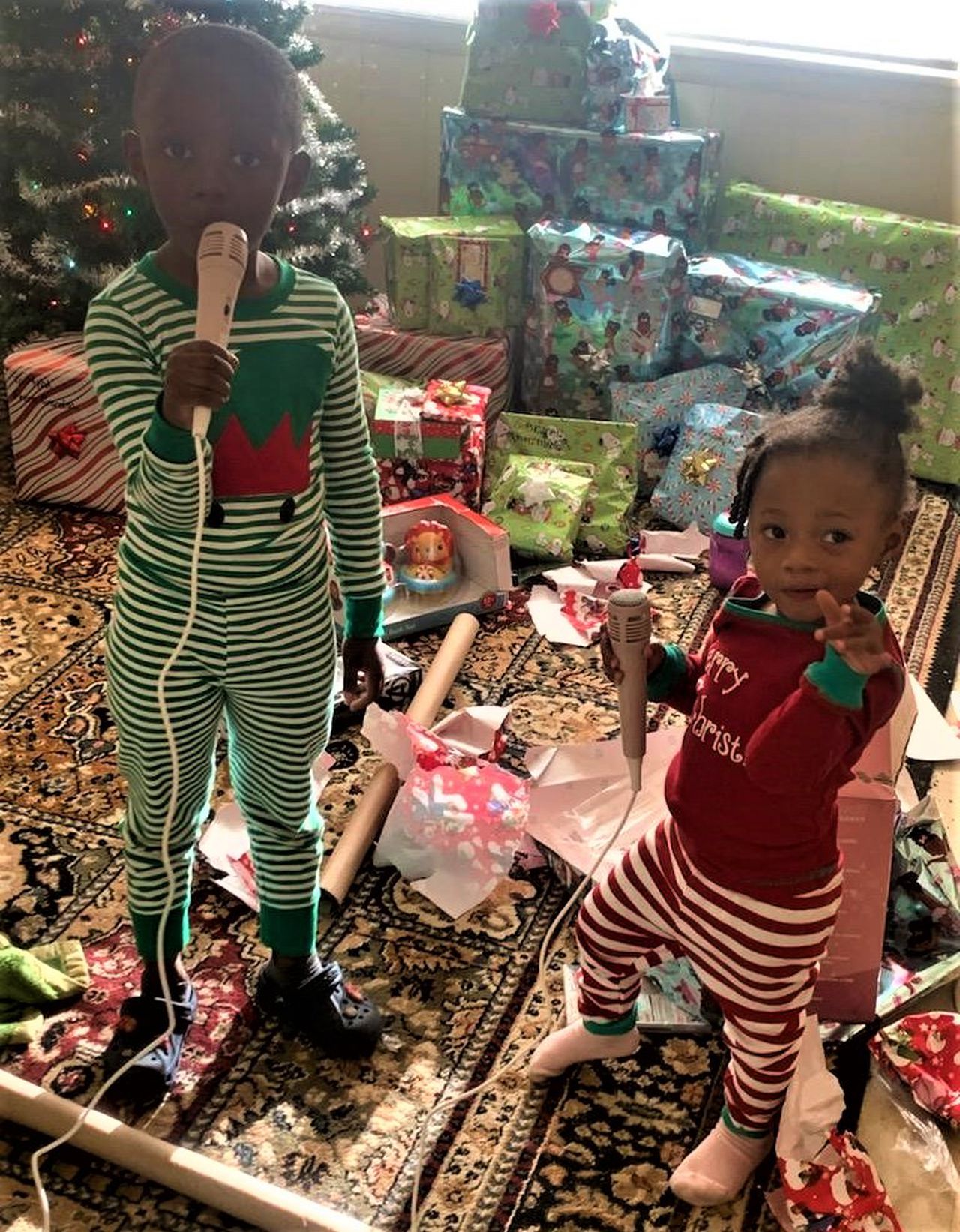

Birmingham’s Miyah Ford was among 110 single mothers who received an unrestricted $375 monthly for a year. It kept her from tumbling over the economic edge, just as guaranteed income has done for other Americans. It helped her two oldest to enjoy Christmas.

Into a place Ford avoided. The guaranteed income allowed her and her children to remain in the apartment. It paid for needed diapers and clothes. “My son’s always growing, his feet are always growing,” she says. “The program came at a good time. It’s pretty much kept me afloat. Had I not had it, I know I would have been stressed all the time.”

The city doesn’t know the identities of all but a few of the women in the program who, like Ford, self-identified. The funds are distributed on a debit card, which allowed tracking of how it was spent. The largest share (34.4%) went to food and groceries, followed closely (31.7%) by retail sales and services. Transportation (13.6%) and housing/utilities (10.6%) were the only other categories exceeding 10%.

This, too, is known: The group averaged 2.1 children in the home and the median annual income was $12,300.

Breathing room. That’s the term Embrace Mothers liaison Sarah A. McMillen, the city’s manager of workforce and talent development, often uses.

“One of the mothers was telling us she selfishly used some of her first payment for something irresponsible,” she recalls. “I’m waiting to hear her say she took a vacation, which, in my opinion, wouldn’t be irresponsible. She said she took her daughters out to dinner, and how much of a luxury it was. They didn’t go to Fleming’s or Perry’s; they went to Captain D’s. She said it was nice for everyone to be able to get what they wanted and not be stressed. That was a wonderful testament that people don’t have a lot of breathing room — a lot of wiggle room month to month.”

Ford is well aware of what you may be thinking. About having children. About their father. About choices.

“Some of my decision-making,” she begins. “Sometimes I wish I could have, like, I don’t regret like anything that happened, but sometimes I feel like maybe if I did things a little bit different or waited a little bit longer to see how things would go that it would have saved me a lot of not having to do some stuff on my own when it came to them.”

Life has a way. Yes, it does.

“From clearing paths to high-wage jobs to closing the gender wage gap, we hope Alabama continues to support innovative solutions that empower mothers and their children to thrive,” adds Bridgeforth.

Embrace Mothers ends next month. The payments stop. Ford still wants to be a surgeon. Believes in her heart she’ll return to nursing school. Maybe it’ll happen one day because she received $375 a month for a year. A year that kept her from the edge.

“I’m going back to work, and I’m gonna get my childcare situated,” she says, “like, who’ll be able to watch them no matter what kind of job I have? It might be a little tough because it was easy when had one kid and somewhat easy when I had two but because all their ages are close together it’s a little bit more difficult now. I’m still getting adjusted to having three kids — a toddler and a newborn.”

Adjusted to life’s way — with a little help. Help from the brink. Guaranteed.

Who wouldn’t want that? Who doesn’t deserve it?

More columns by Roy S. Johnson

We’re saying goodbye to 2022, but can’t shed its legacy of deadly violence

Though my ancestors are listed on Choctaw rolls, tribe won’t let me belong

Put the brakes on illegal street racing foolishness in our killing streets

We’re tired of being mad, thankfully

Miles grad makes largest alum donation in school history, hopes to be catalyst for giving to HBCUs

Roy S. Johnson is a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary and winner of the Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts: “Unjustifiable”, co-hosted with John Archibald. His column appears in The Birmingham News and AL.com, as well as the Huntsville Times, and Mobile Press-Register. Reach him at [email protected], follow him at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj.