From âDonât Ask, Donât Tellâ to âDonât Say Gayâ: 30 years since Clintonâs controversial policy for LGBTQ servicemembers

Two years into her service in the U.S. Air Force, Melissa Johnson was called in for a three-hour meeting where she was questioned about her sexuality.

It was 1983, and Johnson, who was stationed in England at the time, had recently joined the military after graduating high school. She was only 19 years old.

At the meeting, investigators asked her if she was gay, which she denied. She had seen one of her friends who served in the Air Force for ten years be discharged after disclosing her sexuality.

“It was just tearing down every piece of me,” said Johnson in a recent interview, reflecting on the tension and paranoia felt by LGBTQ servicemembers who at the time found themselves at a crossroads between employment and an honest life.

The week following her meeting, she decided to leave the military. “It nearly destroyed me.”

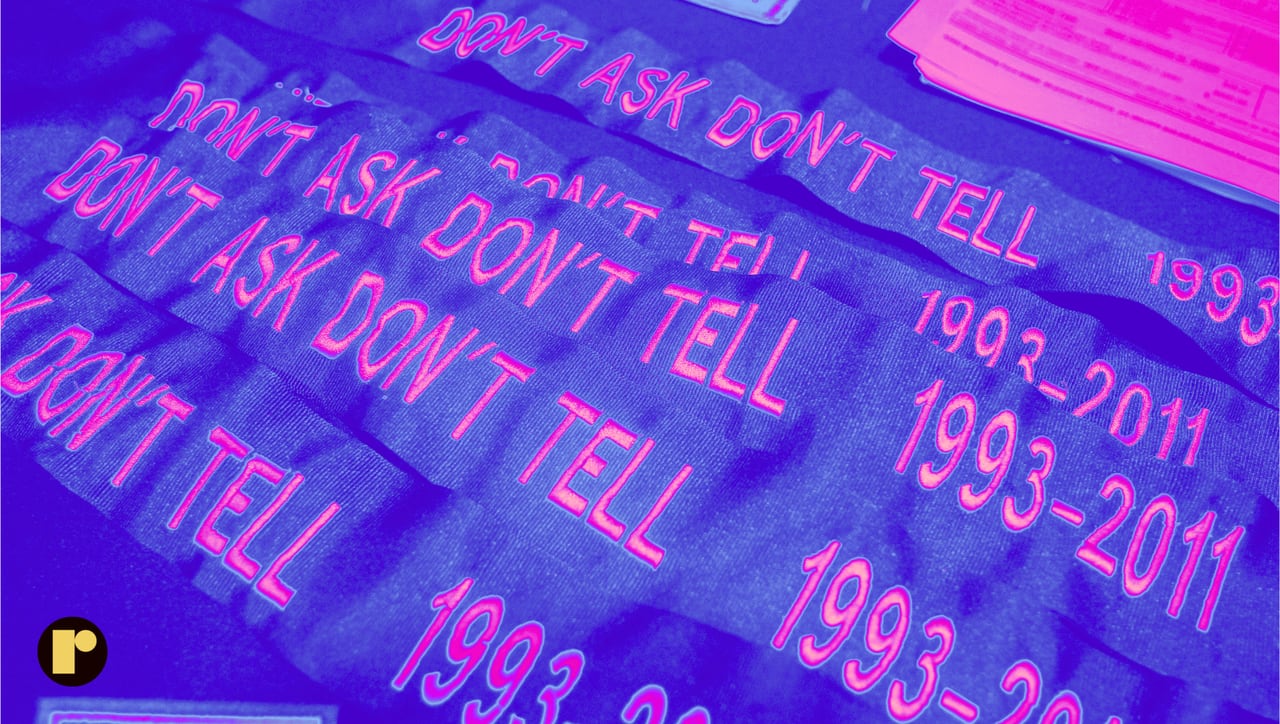

A decade later, on Dec. 21, 1993 President Bill Clinton issued the Department of Defense Directive 1304.26. It instructed the U.S. Armed Forces that recruits and applicants were not to be asked about their sexual orientation, and that those who were allowed to remain in the military were prohibited from disclosing their homosexuality.

Today, it is known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

At the heart of it, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” was “based on the false assumption that the presence of LGBTQ individuals in any branch of the military would undermine the ability of people to carry out their duties,” Human Rights Campaign (HRC) noted on their website.

Over 30,000 servicemembers were discharged from the military from 1980 to 2011 for homosexuality, according to the Department of Defense. This includes servicemembers who were discharged under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell as well as before it was established. A majority of the demographic was white men, according to a Williams Institute study that gathered data from 1994—the first full year of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”—up to its 2010 repeal.

Although Johnson, who now works as a lawyer and serves as the San Diego County Bar Association President, was not officially discharged under the policy, she tells CBS8 that she left the military out of the fear that came with the increased scrutiny LGBTQ people in the military faced at the time.

“When I think about that, it makes me mad,” she told CBS8 on Tuesday. “Because any successes that I would have had, anything I could have done serving our country was just grabbed away from me. And there was nothing I could do about it.”

In 2010, the Senate overturned “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” in a 65-31 vote, which President Barack Obama later signed into law. As a result, gay and lesbian servicemembers were allowed to serve openly, and same gender-attractions—what was a point of contention for LGBTQ people in the military—no longer affected their positions.

In September of this year, the U.S. Department of Defense announced that it would proactively review military records of veterans whose records show that their administrative separation was a direct result of their sexual orientation. According to their statement, the goal is to make amends with LGBTQ veterans who were discriminated against, ultimately correcting their military records that could change the trajectory of their employment opportunities ahead.

Yet for trans workers and LGBTQ youth across the country, the struggle to live openly in schools is only beginning.

A lawsuit in Florida has been filed on Dec. 13, following the firing on Oct. 24 of AV Vary, a nonbinary teacher who taught science at the Florida Virtual School. Vary had started using the gender-neutral honorific “Mx.” at the start of the school year in their email signature without informing the students or school.

The school fired Vary for not complying with the Parental Rights in Education Act, which was signed into law by Republican Gov. DeSantis on Mar. 27. The law, which is informally known as “Don’t Say Gay,” prohibits “classroom discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity” in Florida’s public schools. In the lawsuit, Vary asserts that the basis of their firing was discriminatory and unconstitutional.

“This is a fight for my rights, but this is also a fight for the kindness, compassion and respect for every individual in the country,” they told USA Today on Nov. 10.

Today,Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa and North Carolina have all passed similar bills. While the Florida law prohibits LGBTQ discussions in grades K-3, it was expanded this year up to grade 12 by the Florida board of education, further censoring LGBTQ-related topics and conversations in schools. Meanwhile, Indiana prohibits discussions up until third grade; Arkansas’s law extends to fourth grade; Iowa bans such discussions through sixth grade.

Excluding Arkansas, these bills require teachers to “out” trans students to their parents or guardians at home, an act that PEN America considers “educational intimidation.”

Under DeSantis earlier this May, Florida also signed into law several other bills that target the LGBTQ community—trans people, especially. One of them is House Bill 1521, which criminalizes trans people from using public restrooms, effective this past July.

One of the people targeted was Jodi Jeloudov, a Ukrainian immigrant, an Army veteran and a trans woman. While at the Department of Veterans Affairs medical center in West Palm Beach, Fl. late April, Jeloudov was asked to leave the women’s restroom.

The story went viral when a video clip she recorded during the exchange was uploaded to TikTok. In the clip, a staff member asked her whether she had a “sex change” or was “born a woman.” In an interview with Advocate, she says that armed police officers were called, and she eventually left the property.

Jeloudov tells Reckon that she is also amongst the thousands of people whose status in the military was negatively impacted under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” having been discharged in 2009.

On the 30th anniversary of the Pres. Clinton’s issuing of the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” directive, advocates say that there is a direct throughline to the discriminatory policies that the LGBTQ community faces today. While “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” sought to undermine LGBTQ people’s capabilities, attacks on LGBTQ freedoms like “Don’t Say Gay” seek to paint queer, trans and nonbinary people as a threat to society at large.

Despite Florida’s unwavering efforts to discriminate against its LGBTQ residents, Max Fenning, the founder and Executive Director of PRISM—a youth-led nonprofit that works to expand access to LGBTQ inclusive education and sexual health resources in South Florida—sees a disconnect between Florida’s anti-LGBTQ legislation and the Florida he knows and lives in.

“It’s this contortion and bastardization of people’s real fears of not having control, not knowing what’s going on with their kids and not being able to direct that,” said Fenning. “And legislators have capitalized on that, largely for political gain. I think for them, it’s a low hanging fruit to make people upset, to make people angry, which, unfortunately for some, wins elections.”

Fenning says that with a new legislative session and a presidential election coming up, it’s important to keep the pressure on lawmakers.

“[Things like “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and “Don’t Say Gay”] don’t happen without incident. They will happen if we don’t have anything to say about it—and we sure do and should.”