Thereâs a right way to enjoy a fried shrimp po-boy

If we’re going to talk about fried shrimp po-boys, maybe the best place to start is by admitting that they’re kind of a bad idea.

It’s a sacrilegious thing to say, here on the Gulf Coast, but I’m just being factual: The whole concept of a sandwich sort of hinges on making it with things that can reasonably be expected to stay in the sandwich. Slices of meat and cheese and tomato. Spreads that cling to the bread. Leaves of lettuce. Piles of slow-cooked roast beef. Medium-sized fried shrimp do not fit the bill. They’re irregular, they don’t layer particularly well and, barring the use of a bonding agent such as tarter sauce in large quantities, have no tendency whatsoever to clump together.

Also, they’ve already been individually wrapped in breading, so how did somebody come up with the idea that what was needed was more bread?

Fortunately for us all, food is a realm where ideas that sound really bad in theory frequently turn out to be really fun in practice. And here we are, living in a world where a sizeable percentage of the fried shrimp eaten in Lower Alabama are served on sandwiches that generally do a lousy job of containing them, to the perfect satisfaction of the people trying to eat them.

Why?

The question took me to the Original Oyster House on the Causeway. There probably are a thousand places in coastal Alabama where you can get a fried shrimp po-boy, and they’re mostly pretty good. It’s possible to screw one up, but let’s face it: While there is a knack to frying shrimp properly, it’s not a culinary challenge on the order of making the perfect souffle.

What really drew me to the Original Oyster House was my theory that if you’re looking for the optimal shrimp po-boy experience, the view matters. Lots of landlocked places serve great ones – but if you want to enjoy one to the fullest, you need to be on the water’s edge.

Maybe I just had Thanksgiving on the brain, but I think it has something to do with gratitude.

The po-boy’s mission statement is right there in its name. It’s a humble dish. A big handful of food for the working man. That’s a universal concept, but the coastal influence warps it. When you live on the coast, even a poor boy gets to enjoy the bounty of the Gulf. You might not be able to afford the elaborately prepared catch of the day at market price in some elegant Orange Beach establishment. But when the sandwich in your hands is literally overflowing with shrimp that theoretically might have come from waters you can see, it’s hard not to feel well-off.

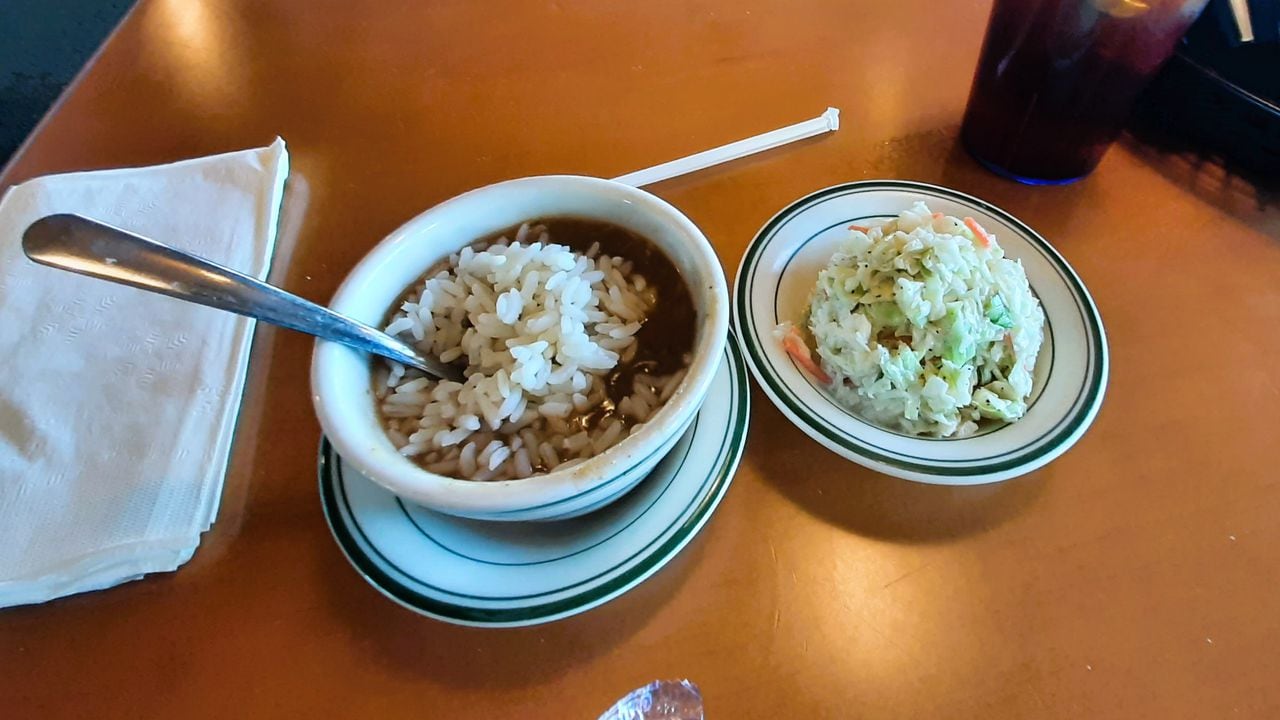

A cup of gumbo and the usual side of slaw at the Original Oyster House on Mobile’s Causeway.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

The Oyster House sandwich, arriving after an obligatory cup of gumbo and a ramekin of some really excellent slaw, fit the bill perfectly. At first glance it didn’t even look like a sandwich, just a pile of fried shrimp atop pickles and lettuce and tomatoes and fries. Upon closer examination, edges of bread were visible here and there around the perimeter. This only served to rise the question: How the heck is a person supposed to fold this mass up into an actual sandwich?

As best you can, poor boy, as best you can. Shrimp are going to escape, but we’re not going to let them get far, are we?

No. We’re going to take a bite. Then we’re going to take stock: Is there a gap that needs to be filled, before we take the next bite? No problem. We’ll collect a few strays from the plate, stuff them into place, and take the next bite. We’ll keep doing this until it’s all gone. It’s like you’re Scrooge McDuck, trying to hold more gold coins that your hands can contain.

And that view: The best ones at the Original Oyster House face north, giving a panoramic view from Mobile’s industrial waterfront to the open wilds of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta. To the west: The thicket of shipping cranes, more numerous now that in past, at the state docks. Government Plaza. The RSA Tower. A little farther north, Africatown Bridge.

A view of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, as seen from a window of the Original Oyster House on Mobile’s Causeway.Lawrence Specker | [email protected]

And then, continuing from left to right, the Delta. To a visitor, it must not look like much, just a windswept vastness of tall marsh vegetation and defiant trees, settling from the green of summer into the brown and gray of winter.

But if you’re from here, or if you’ve been here a while, you see more and you know there’s more that can’t be seen. Waterways (like the one running right under the window) that you might have traveled by boat. Winding, watery paths and hidden lakes known to fishers and hunters. Camping platforms for kayakers, put there by the state and available to anyone who wants to spend a night in the middle of it all.

Take a bite, round up strays, repack, take a bite. Take your time. The view isn’t going away. Neither is the feeling it all belongs to you somehow. If Toyota designed cars like human beings designed this sandwich, they’d have gone out of business years ago. But the fried shrimp po-boy is a great sandwich, partly because there’s no way you can eat it on the go. You simply have to sit and ponder things, while you’re working on it.

And then the last shrimp is gone. Normally I’d want a little remoulade or tartar sauce, but this one was just fine as served. They know what they’re doing, at the Oyster House.

Weirdly, for something that started out overflowing with shrimp, you always seem to end up with a last bite that’s all bread, maybe with a scrap of lettuce or tomato left. You might as well eat that too.

And then it’s time to get on with your day, and maybe you’re a little more refreshed than you would have been after some other meal. This one made you stop. This one made you put down your phone and look around, because you needed two hands. This one gave you a few minutes of thinking about how life is good.

What did you eat? A structurally unsound sandwich named for its down-to-earth target demographic. How did you eat? Like a king.