The enduring legacy of Horace King, Alabamaâs master bridge builder

AL.com’s “Alabama Vintage” project explores inclusive stories and photos from archives and readers. Follow the project on Instagram @alabamavintage.

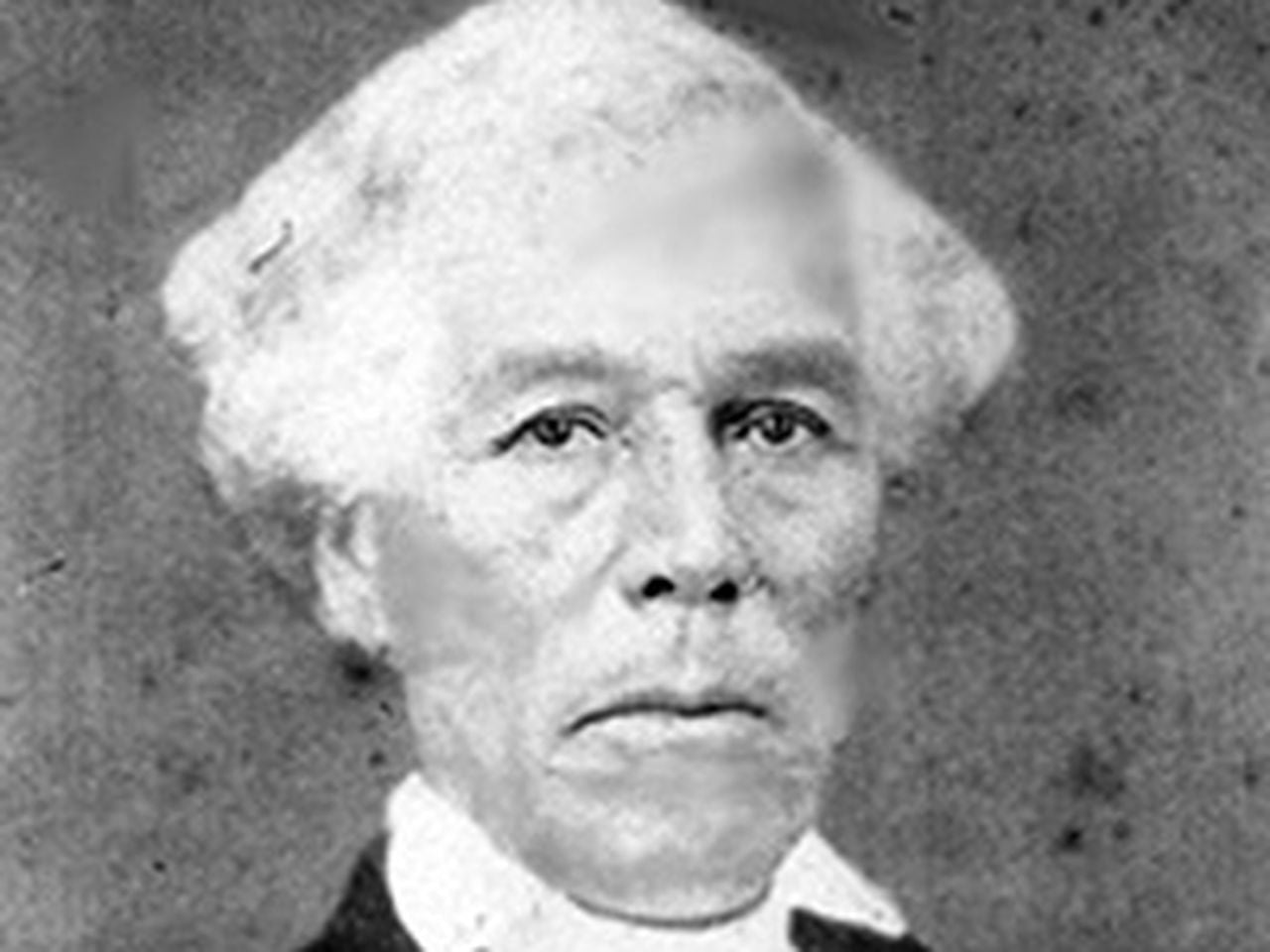

Very few people can stake their claim to the building of the south quite like Horace King. He remains one of the most important architects to step foot in Alabama.

He was responsible for numerous feats of architecture that remain visible today, such as spiral staircases found in homes like Spring Villa Mansion and in the state’s very own capitol building.

His story begins in 1807, where he was born into slavery in South Carolina. Unlike most enslaved people, he was taught to read and write at a young age. Around 1830, King was purchased by contractor John Godwin. King learned how to build under Godwin and received some of his most important training under the noted architect and bridge builder Ithiel Town – one of the first professional architects in the United States. Town was well-known for Federal and Greek Revival building designs on the East Coast.

Godwin experienced financial difficulty in the late 1830s and transferred ownership of King to his wife and her uncle, in a move thought to protect King from being taken by creditors.

In the mid-1830s, Godwin sent King to Oberlin College in Ohio, the first college in the country to admit Black students. Following his education, King returned to work with Godwin, building courthouses and bridges throughout Georgia and Alabama.

Before the turn of the 1840′s, he was allowed to marry. His wife was a free woman named Frances Gould Thomas. In the 1840s, King and Godwin were officially considered “co-builders”, which would be another rarity for a Black man in the South at this time. In 1841, they rebuilt the Columbus City Bridge after it was destroyed in a flood.

King’s skill and reputation surpassed Godwin’s and he began working independently. He made friends such as Robert Jemison Jr., an attorney, senator and entrepreneur in Alabama, who had King supervise major bridge construction for him.

Another rare allowance for King was that he was permitted to keep some of his earnings and gained the opportunity to buy his freedom in 1846. Under Alabama law, he was only allowed to remain in the state for one year after purchasing freedom. Jemison used his seat in the Alabama State Senate to arrange legislation allowing King to remain in Alabama as a free man.

King went on to construct Moore’s Bridge over the Chattahoochee River near Whitesburg, Georgia, and gained monetary interest in the bridge. He moved his family near the bridge in 1858 and they collected bridge tolls and farmed land while King continued building buildings and bridges throughout the South.

When the Civil War began, King was conscripted by the Confederate army to build obstructions and defenses along the Apalachicola River and Alabama River. In 1863, he was moved back to Columbus to build a mill that manufactured cladding for Confederate warships.

After the war, King maintained that he had always been a Unionist, and that he always “begged and talked for the Union.”

Many of his bridges were destroyed during the Civil War, including Moore’s Bridge and the Columbus City Bridge. He rebuilt the Columbus City Bridge a the third time after the war. He also orchestrated factories, buildings and several bridges along the Chattahoochee basin.

In 1867, King became a registrar for voters in Russell County, Alabama. In 1868 he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives as part of a wave of Black office holders and was reelected in 1870. He did not seek reelection for a third term.

King moved his family again to LaGrange, Georgia. He trained his children in construction as he continued building. By the mid-1870s, he started passing projects onto his children, who formed King Brothers Bridge Company. Horace King himself built nearly the entire east side of LaGrange’s downtown square and parts of the north side.

King died in May of 1885. It was reported in all major Georgia newspapers – again, another rare position for a Black man in the South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama.

Many of the original buildings designed and built by King were lost to time, but his influence is evident across the entire Southeast.