Roy S. Johnson: Bubba Copeland’s business was none of ours

This is an opinion column.

I knew. Or knew enough to ask. I didn’t.

It was the fall of 1992. Not long before, Earvin (Magic) Johnson, then at the prime of his NBA. Hall of Fame career, shocked us all by announcing he was HIV positive. Back then, we thought he’d soon be dead.

It was the nascent days of the AIDS virus, a time long before viable treatments. Long, long before the stigma of being HIV positive dissolved in all but the deepest crevices of inhumanity.

Having co-authored an autobiography with Earvin—and obtained an exclusive interview with him backstage at the Arsenio Hall Show a day following the announcement—it was widely known we were connected. As someone who’d also covered tennis for several years, it was also widely known I was close with Arthur Ashe.

By then the three-time grand slam champion was a statesman not just for the sport, or even sports. For right. Human rights. He called out injustice no matter where it resided. He was one of the first noted figures to lend his name—and be arrested for protesting apartheid in South Africa and the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela.

Arthur and I knew each other professionally and socially. We navigated the fine line—journalist (I covered tennis as a reporter at The New York Times I was oversaw coverage of it as a senior editor at Sports Illustrated) and public figure—both of us mindful and respectful of it.

My phone rang. On the other end was a credible tennis figure. “You know about Arthur Ashe,” they said. “He’s got AIDS.”

I could have asked. I didn’t.

A few weeks later another caller shared the same disheartening message.

I could have asked. I didn’t.

I didn’t even tell my boss, SI’s managing editor.

I certainly could have. Arthur was a public figure, which gives journalists the right to ask—and publish—just about anything about someone, as long as it’s true.

You don’t want to arm-wrestle me over the First Amendment and freedom of the press. You’ll lose.

I could have asked. I didn’t.

I saw Arthur several times after those calls. He and his amazing and talented wife, Jeanne Moutoussamy Ashe, were my guests at the annual United Negro College Fund’s charity dinner in New York. Magic was one of the honorees.

As I later wrote in SI, in a column on why I did not ask Arthur about his health: “At one point the discussion at our table turned to Johnson’s efforts to promote AIDS education and awareness, but by then I had just about put the calls about Arthur out of my mind. I had decided that if he wanted me to know about his condition, he would tell me. Otherwise, it wasn’t my business. I had placed his privacy ahead of any desire to break the story in SI—and it wasn’t a tough decision.”

It wasn’t tough because I chose humanity and empathy over exclusive.

I chose compassion and concern over journalistic competition.

Arthur, I reasoned, was not the CEO of a public company with employees and shareholders depending on him. He was not an elected official. Not a healthcare worker. Not an active athlete. Had he held any of those roles, the scale would have easily tipped towards my pen (or keyboard) and I would have asked.

He did not, so I didn’t.

I shared my thinking in SI because not long after the dinner, USA Today made another choice. Based on a tip similar to the one I received, they assigned a reporter, one who’d known Arthur since the two were young, to confront him.

Arthur, then 48 years old, did not confirm or deny having AIDS, though the inquiry pushed him to reveal his secret. The following day, with Jeanne by his side, he emotionally revealed doctors told him he had AIDS in September 1988 after undergoing brain surgery to determine the cause of paralysis. A blood transfusion during a prior surgery—he had cardia-bypass procedures in 1979 and 1983—was the source of the infection.

“I am angry,” Arthur said that day, “that I was put in the position of having to lie if I wanted to protect my privacy.”

Less than a year later, Arthur died.

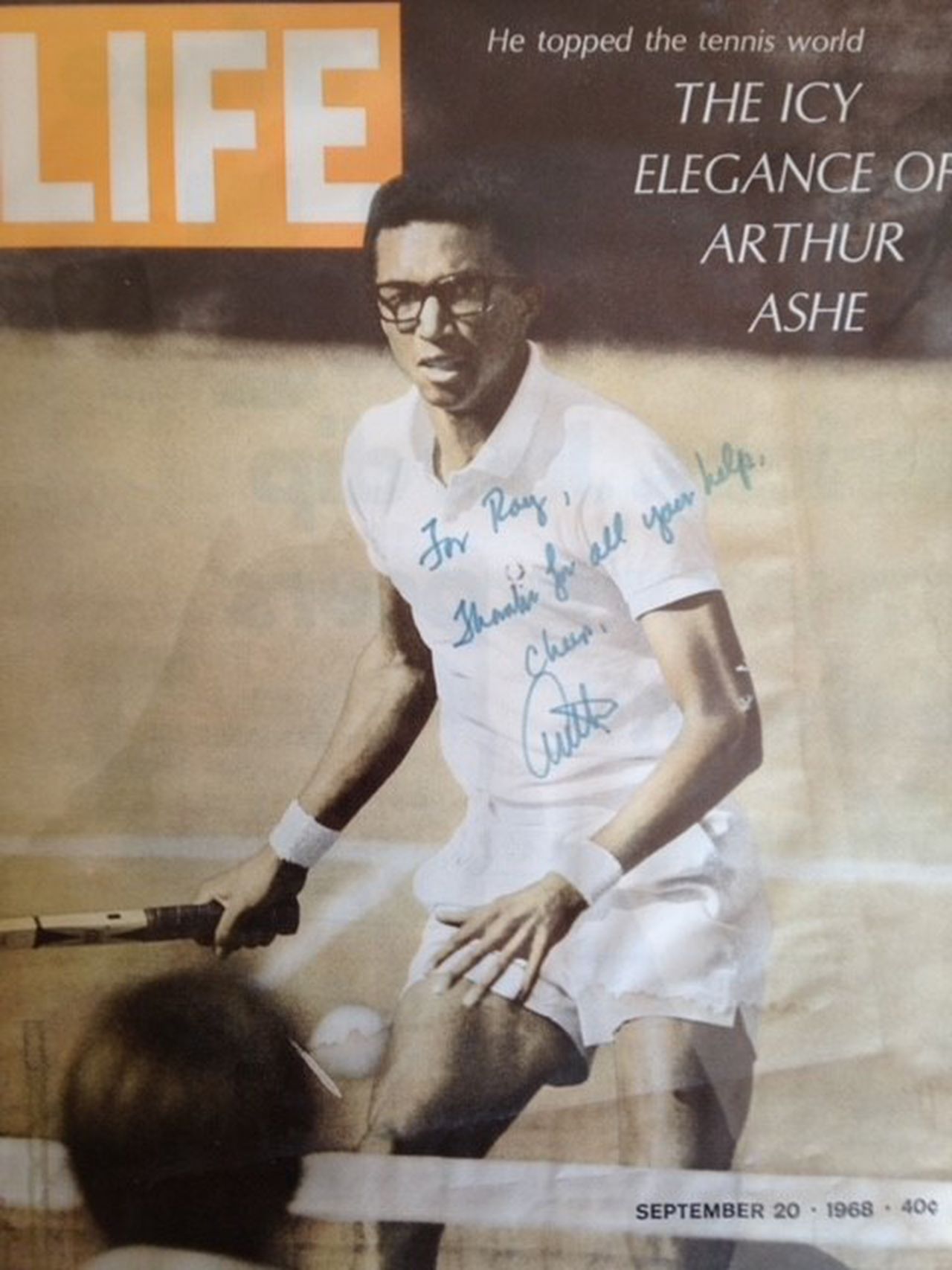

LIFE cover of Arthur Ashe, signed to now AL.com columnist Roy S. JohnsonLife magazine

Last week, a God-loving man—and public figure—chose to end his life two days after 1819 News published photos of him wearing women’s clothing and makeup.

Last Wednesday, the day the images were published, F.L. “Bubba” Copeland, mayor of Smiths Station and pastor at First Baptist Church in Phenix City, told congregants he was a “victim of an Internet attack.”

“The article is not who or what I am,” he said from the pulpit. “….I apologize for any embarrassment caused by my private and personal life that has become public. This will not cause my life to change… “

After a brief sermon, he said: “God will always protect you, take care of you. He will see you through anything, absolutely anything.”

Late afternoon that Friday, Copeland, with law enforcement in slow pursuit after being called to a welfare check, pulled over on Lee County Road 275 just north of Yarbrough’s Crossroads.

From the sheriff: “He exited the vehicle, produced a handgun, and took his own life.”

Copeland was an elected official and, certainly, a public official.

Yet just because we can doesn’t mean we always should. Just because we have the right to publish doesn’t mean we should always exercise it.

Back in 1992, I wrote: “Overwhelming public ignorance remains one of [the spread of AIDS] greatest allies.”

Ignorance about how the disease was transmitted. Ignorance, I wrote, “that people afflicted with AIDS somehow deserve their fate.”

Ignorance that cultivated a pitchfork frenzy that took decades to diminish—though, sadly, it has not dissipated.

It lingers today in overwhelming public ignorance about sexual lifestyles, about gender. In the new pitchfork frenzy against those who live and love their own way.

In our overwhelming loss of our humanity and empathy, of our compassion.

Ignorance lingers in a choice made, a choice to publish, which sparked a tragic, deadly choice.

The headline on my 1992 SI column was simple: “None of Our Business.”

It still isn’t.

If you or someone you know is contemplating suicide, reach out to the 24–hour National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741; or chat with someone online at suicidepreventionlifeline.org. The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is available 24 hours.

I’m a Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary, a member of the National Association of Black Journalists Hall of Fame, and winner of the Edward R. Murrow prize for podcasts for “Unjustifiable,” co-hosted with John Archibald. My column appears in AL.com, as well as the Lede. Check out my new podcast series “Panther: Blueprint for Black Power,” which I co-host with Eunice Elliott. Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter, The Barbershop, here. Reach me at [email protected], follow me at twitter.com/roysj, or on Instagram @roysj