Why itâs more important than ever to learn about the history of Filipino American activism

Filipino history has always been very complex — and there’s a lot about Filipino Americans that have been ignored in classrooms and textbooks. While some might know about the history of U.S. imperialism and Spanish colonization, there’s lesser known history about the solidarity between Filipino Americans with Latino, Black, and Indigenous communities.

According to Kevin Nadal, a professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, the history of Filipino Americans and building coalitions with other groups fighting for social justice, dates back to when Filipinos first arrived in the United States in 1587.

He spoke about everything from Filipinos that fought the civil war with the North in fighting for the freedom of enslaved people in the United States, to more contemporary moments, including the time when Filipinos fought alongside Mexican American farm workers during the Delano grape strike in 1965.

“Understanding the true history of Filipino — or Asian American people — in this country, and recognizing the amount of struggle and oppression as well as resilience and activism that previous generations have done to give them the liberties that they have today can help them to better understand and appreciate their own identities,” Nadal said.

Larry Itilong, a Filipino American labor organizer, was one of the prominent leaders in the Delano grape strike, when he joined forces with Mexican American labor and civil rights activist César Chávez to fight for better wages.

In recent years, more literature has come out about Itliong. For instance, Historian Dawn Mabalon, who passed away in 2018, and writer, artist, and activist Gayle Romasanta wrote the children’s book, Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong. Romasanta also wrote Larry: The Musical based on the book which was performed in San Francisco earlier this year.

The story of Itliong striking alongside Chávez and Mexican Americans shows not only the strong bond Filipino Americans had with the Latino community, but it was one of the prominent examples of solidarity as well as the fight for better wages.

Solidarity across racial lines

There’s also many instances of Black-Filipino solidarity — and vice versa — including when Black soldiers fought alongside Filipinos during the Philippine-American War, which took place from 1899 to 1902, and chronicled Filipinos’ fight for independence from the United States following the end of the Spanish-American War. In the 1970s, when police officers raided the International Hotel in San Francisco to evict Chinese and Filipino residents, students which consisted of Indigenous people of the Reclaim Alcatraz movement and Black Panthers.

“There’s been more than a century and a half of Black-Filipino solidarity that we don’t really talk about that much,” New York-based queer/non-binary writer, dancer, and activist Rhou Zhou-Lee said. They wrote an essay for Reappropriate last year that went in detail about some of those documented histories.

Nadal also spoke about the history of Filipinos fighting alongside Black, Latino, Native American, and other Asian groups for ethnic studies at San Francisco State University — and later UC Berkeley. The former movement was later known as the Third World Liberation Front strikes of 1968.

“Being Filipino — given our history of colonialism and fighting against oppression — it’s part of our fighting spirit,” Nadal said. “It’s something that has always been there. Maybe we have suffered from oppression and colonialism and injustice. But at some point, Filipinos will stand up and say ‘We won’t take this anymore.’ We’re going to fight for what’s right.”

Nadal mentioned that there are many Filipinos presently fighting for the Free Palestine Movement, which defends and advocates for the human rights of all Palestinians. Other Filipino-led movements like GABRIELA USA and BAYAN USA have been vocal about their support for Palestinians amid the Israel-Hamas war, which has recently put the spotlight on the decades-long conflict between Israel and Palestine.

A legacy spans generations

Nicole Salaver, project manager at San Francisco-based nonprofit economic and arts organization Kultivate Labs and host of the Cultural Kultivators podcast, is the niece of Pat Salaver, who was instrumental in the founding of the Third World Liberation Front as well as what is now known as Pilipinx American Collegiate Endeavor. Salaver said before that, Pat had a connection to Itliong (who was Pat’s uncle through marriage) and would go to the Delano strikes as a teenager.

“You know how in the movie Forrest Gump where Forrest just happened to be at all these important historical events?” Salaver said. “Somewhat similar to my Uncle Pat Salaver, he was there during the Delano strikes and he was there during the [San Francisco] I-Hotel protests.”According to Salaver, her uncle was a student at San Francisco State University in 1967. “At the time, even though Filipinos represented like one in three of the population in San Francisco, there was still a majority of Filipinos coming to study at SF State, but they didn’t have a political organization to align with,” Salaver said.

She said he was inspired by the strong organizational structure and political activism of the Black Student Union (BSU), so he asked to join since there was no student organization dedicated to Filipino students. While they didn’t reject him, BSU along with Dr. Juan Martinez, a history professor at SF State, encouraged him to start his own Filipino organization to march and protest in solidarity with BSU and the other student activist groups.

From there, PACE was officially born and became one of the groups that made up the Third World Liberation Front, the Latin American Student Organization, the Mexican American Student Confederatio, and the Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action. With that movement, the student groups led a five-month strike on campus to protest the college’s admission practices and curriculum which often excluded nonwhite students.

Later after Pat dropped out of college to support his family, he was imprisoned for two years after refusing to fight in the Vietnam War. Salavar said that after he was pardoned, his fire for political action was washed out and he felt regret for not being able to be there for his family during that time.

He passed away in 2019. While Salaver said her Uncle Pat felt shame and guilt for being away from his family during that time, he has made a huge impact in the community and continues to inspire the work she does as well.

“He definitely created change,” she said. Salaver said she’s currently working on a script about her uncle which she hopes to develop in the next few years.

Filipinxs for Black Lives

Kalaya’an Mendoza, is a queer and hard of hearing human rights defender, street media, and community and safety and mutual protection trainer, whose activism began in the ‘90s when he was a teen fighting to have the San Jose Police Department removed from his high school campus for discriminating against Filipino, Vietnamese, and Mexican youth.

Mendoza worked closely with the Free Tibet movement in 2008 and was at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in support of the Indigenous community. In recent years, Mendoza has also been essential in the Black Lives Matter movement.

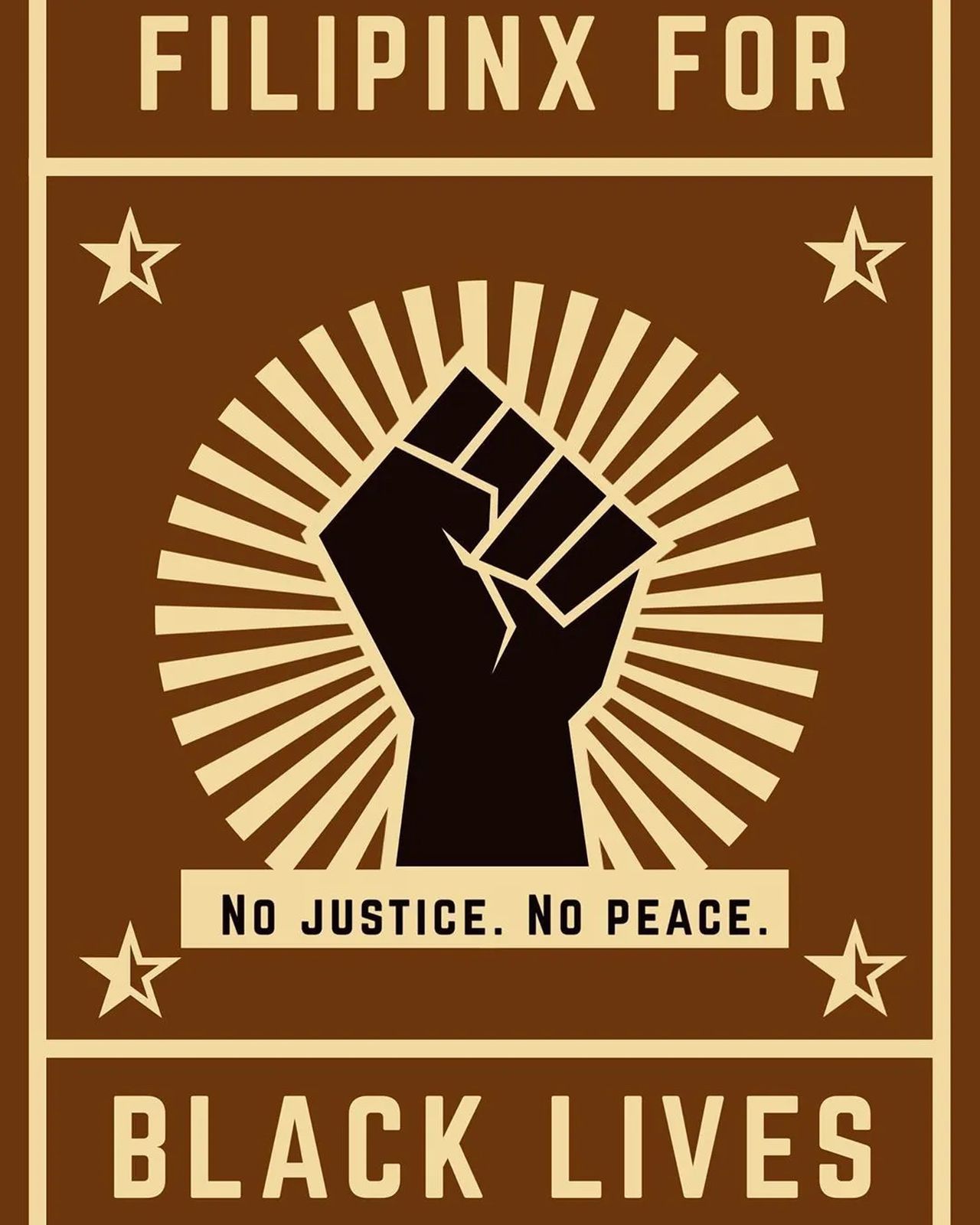

Filipinx for Black Lives poster created in 2019 in honor of Eric Garner’s fifth death anniversary.

During the Ferguson protests in 2014 following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, Mendoza said he was on the ground as a human rights observer protesting communities from state violence.

“I don’t like transactional solidarity,” Mendoza said. “I don’t like the whole ‘Black folks showed up for us, now we have to show up for them.’ Unless we actually see that our fates are interlinked and intertwined, this has to be about transformational solidarity not transactional, or things are not necessarily going to change for our communities.”

Mendoza also created the poster campaign for “Asians for Black Lives” and “Filipinx for Black Lives” in 2019 on the fifth anniversary of Eric Garner’s death. The design features a raised Black power fist surrounded by golden Philippine sun rays as a way to center the lives, struggles, and liberation of Black people.