New congressional district map carves up Mobile

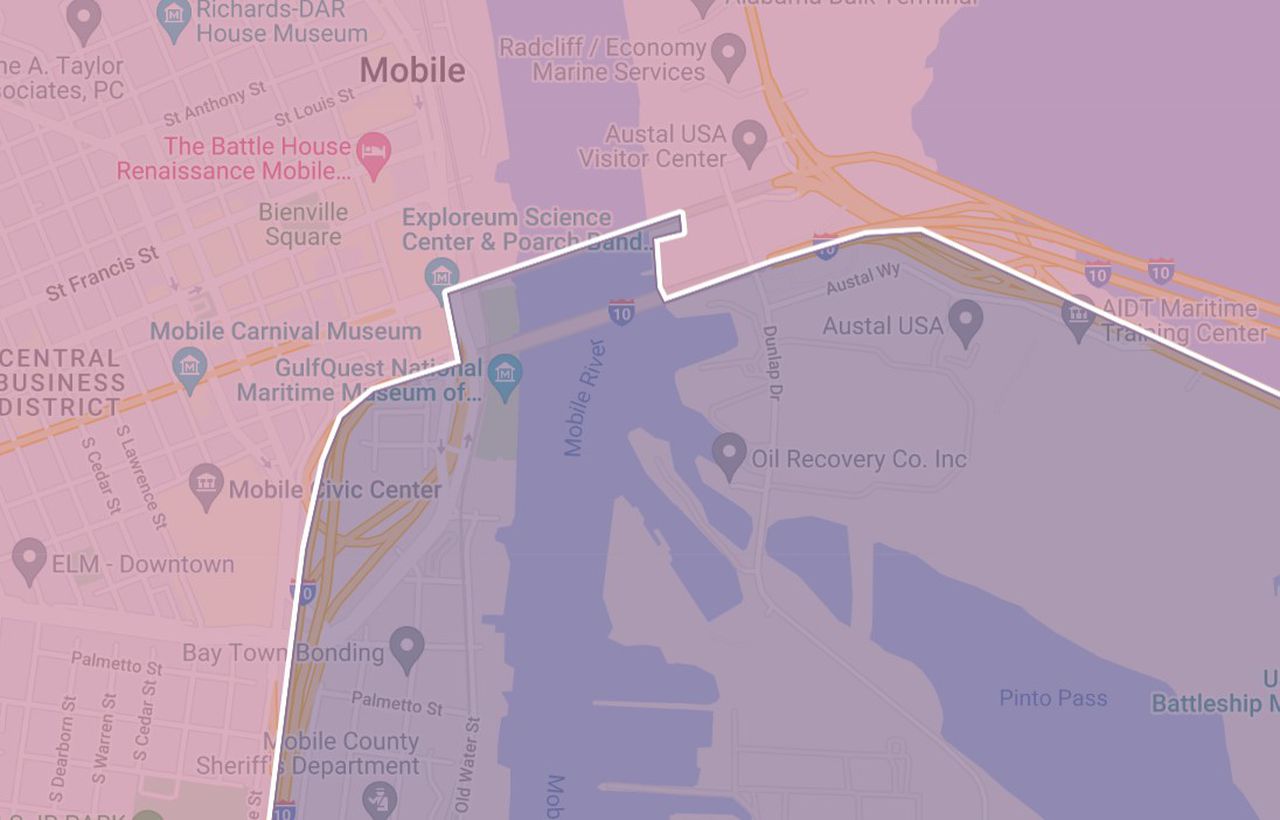

The Austal USA manufacturing facility will continue building warships within Alabama’s 1st congressional district, but the company’s visitor’s center is now in Alabama’s 2nd congressional district.

In downtown Mobile, museums and attractions are between the two congressional districts, depending on which side of Water Street they are on. And further south into Tillman’s Corner, the district’s boundaries split the community into two.

Related content:

Right-leaning Republican areas like Semmes, Citronelle, the Village of Spring Hill and into west Mobile are now lumped into the competitive District 2. Saraland, Satsuma, and the University of Mobile remain in highly conservative District 1.

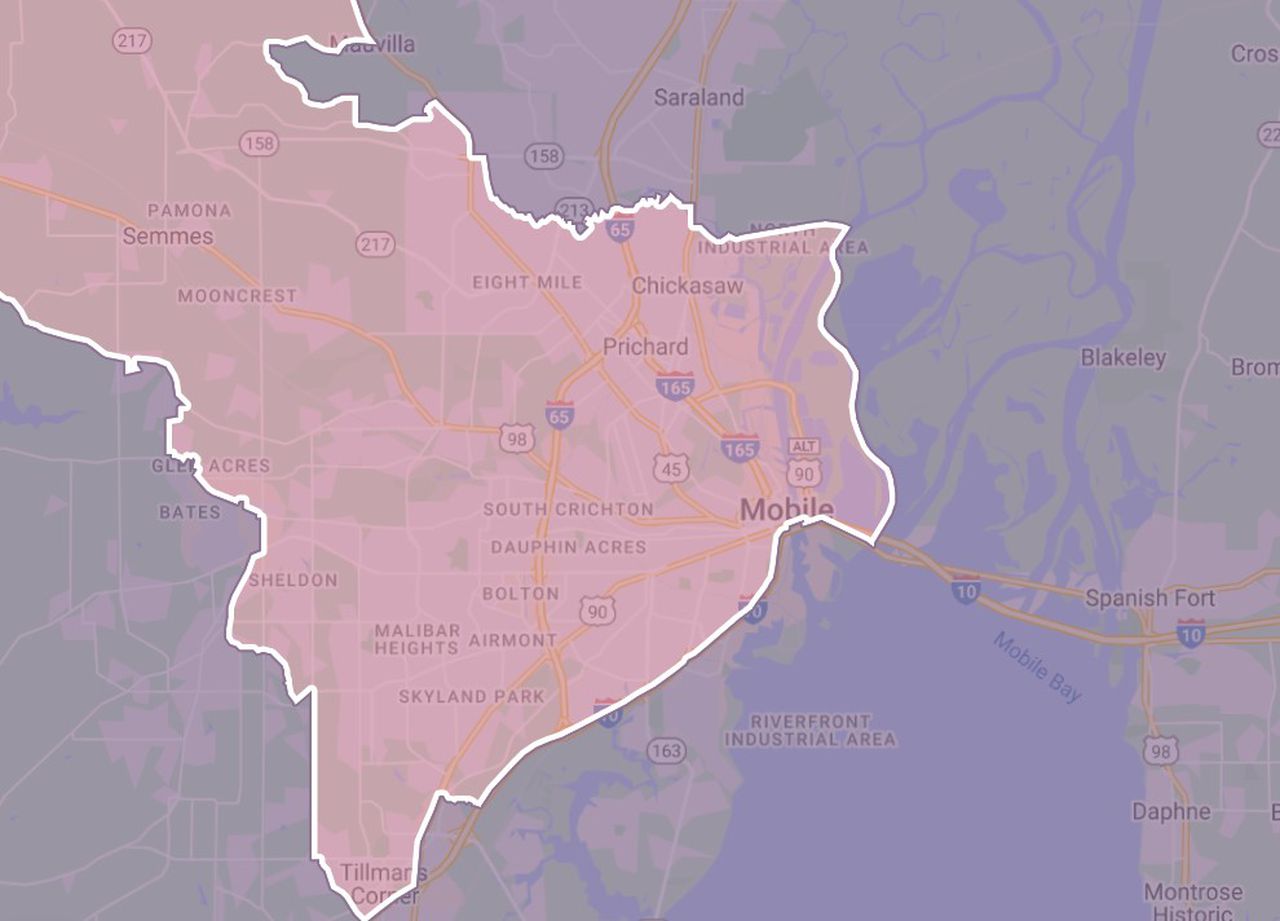

For Mobile County, the newly approved congressional map is carving up a city and county into two distinct congressional districts for the first time in recent memory. Residents and business owners long used to inclusion in the 1st district will need to check the newly-drawn map for where they fall within the new boundaries. In many cases, the difference between voting in the two districts depends on which side of the street you are on.

Mobile’s 2nd district

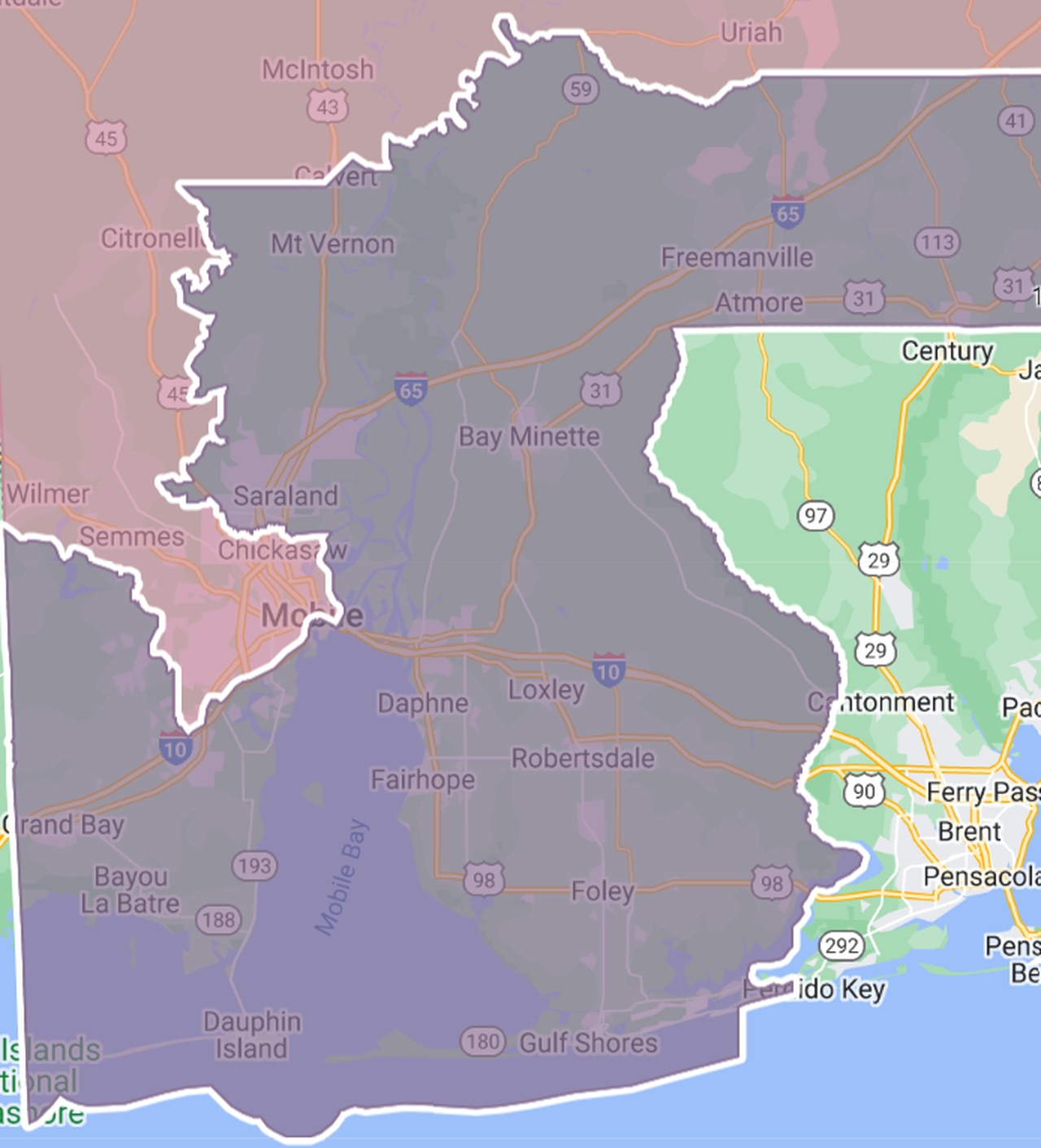

The new Alabama congressional boundaries in South Alabama, dividing District 2 (red) from District 1 (gray).

Much of the city will be included in the 2nd congressional district. It will be lumped into a sprawling east-west congressional district that includes the City of Montgomery, Troy, Eufaula, Tuskegee, Greenville, Union Springs, Evergreen, and Frisco City.

“Politically, what it does, is enhances a Mobile candidate in that 2nd district,” said Steve Flowers, a longtime state political commentator and former Republican member of the Alabama State House of Representatives.

The new map, referred to as Remedial Map 3, was chosen Thursday by a three-judge federal panel to serve as Alabama’s new congressional map for the 2024 elections. The map was drawn by a court-appointed special master and creates a new purple 2nd congressional district running from Mobile County in Tillman’s Corner north through the southern Black Belt to the Georgia border. It has a Black Voting Age population of 48.7%, which is only slightly more than the other maps that had been under consideration.

U.S. Rep. Jerry Carl (left) and Rep. Barry Moore (right)

District 2 no longer has a sitting congressman living within its boundaries. District 1 has two Republican incumbents within its borders – Rep. Jerry Carl, who lives in South Mobile County, and Barry Moore of Enterprise. Carl has said he intends to seek re-election next year, while Moore hasn’t committed.

Alabama’s 7th Congressional District in West Alabama and Jefferson County, will have a Black Voting Age population of nearly 52%.

The new maps, instead of six safe Republican districts and one safe Democratic district, will now have two districts where Democrats have a realistic chance to win.

State Rep. Sam Jones, D-Mobile, said the new map makes Mobile a factor in the Democratic primary for the 2nd district, where Montgomery Mayor Steven Reed has been considered a strong contender for the seat. In Mobile County, Democratic state Senator Vivian Figures and Rep. Napoleon Bracy of Prichard have both expressed interest in running.

“Mobile will play a tremendous factor on who gets elected,” said Jones, the city’s first Black mayor who served in that position from 2005-2013. “If someone from Montgomery runs for this district or someone from other parts of the state runs for this district, they got to come and appeal to Mobile. There is no way they can try and establish support without Mobile.”

Divided Mobile

The downtown Mobile skyline stands in the shadows of the Interstate 10 Bayway as it approaches Daphne, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

The splintering of Mobile has incensed officials who believe it separates so-called “communities of interest,” namely by splitting much of the city from neighboring Baldwin County. A community of interest, by definition, is a neighborhood or groups of people who have common policy concerns and would benefit from being maintained in a single district.

Others are upset because of the divide through Mobile, and the logistical headaches it imposes on whomever is elected to represent the congressional districts.

The new Alabama congressional boundaries in South Alabama, dividing District 2 (red) from District 1 (gray).

“The map is a travesty,” said Quin Hillyer, a conservative writer for The Washington Examiner, who submitted a proposed map for the judges to consider aimed at keeping Mobile together. Hillyer ran for the 1st congressional seat as a Republican in 2013.

“It bizarrely divides Mobile — both county and city — by acting as if Black Mobilians have more common interests with residents of Eufaula than with the neighbors in Mobile,” Hillyer said in a statement to AL.com. “The fastest way from mid-town Mobile to Eufaula is to start in Congressional District 2, drive through Congressional District 1, leave the state entirely and drive for hours in Florida, almost all the way to its capital in Tallahassee, then re-enter Alabama District 1, drive through part of it, and finally come back into District 2. That’s insane, and arguably unconstitutional.”

The new Alabama congressional boundaries in South Alabama, dividing District 2 (red) from District 1 (gray).

Supporters of the new congressional maps, including Mobile County Democrats, say it’s not a big deal for Mobile to be separated with Baldwin County. But Democrats also say their own party objected to the map because the Black voting age populations were too low.

Joe Reed, longtime head of the Alabama Democratic Conference, objected to all three of the maps the judges had under consideration. Alabama Republicans, including Secretary of State Wes Allen, also objected to the three maps.

Court challenge

The map is the result of successful court challenges in Allen v. Milligan that began in 2022, over a congressional map drawn in 2021 by an Alabama Legislature run by a supermajority of Republicans.

The federal panel, consisting of two judges appointed by former Republican President Donald Trump, ruled the map was unconstitutional and violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965. They ordered lawmakers to redraw it, which was done during a special session in July.

But the court found that the redrawn map did not fix the problems and ordered a special master to submit three maps. The plaintiffs in the case preferred Remedial Map 1 – which contained two congressional districts with a majority Black voting age populations – but also saw Map 3 as a good alternative.

The state twice took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. And both times, the nation’s highest court has affirmed the lower court’s orders.

The overriding concern throughout the case has been over Alabama’s tradition of racial polarized voting that historically shows white voters overwhelmingly backing Republican candidates, while Black votes support Democrats. More than a quarter of the state’s residents are Black.

In Alabama’s Gulf Coast, the concern among Republicans has mostly focused on splitting Mobile County and merging it with the Black Belt and Montgomery. The courts supported the split in order to obtained the desired racial demographics giving Black voters a chance to have representation of their choice.

Alabama, since 1992, has only had one majority Black congressional district since Reconstruction and only three Black members of Congress have been elected from the state, all from Alabama’s 7th congressional district – Earl Hilliard, Artur Davis, and Terri Sewell.