Do âclothes make the manâ? Ask Gandhi, a soldier or a punk rock star

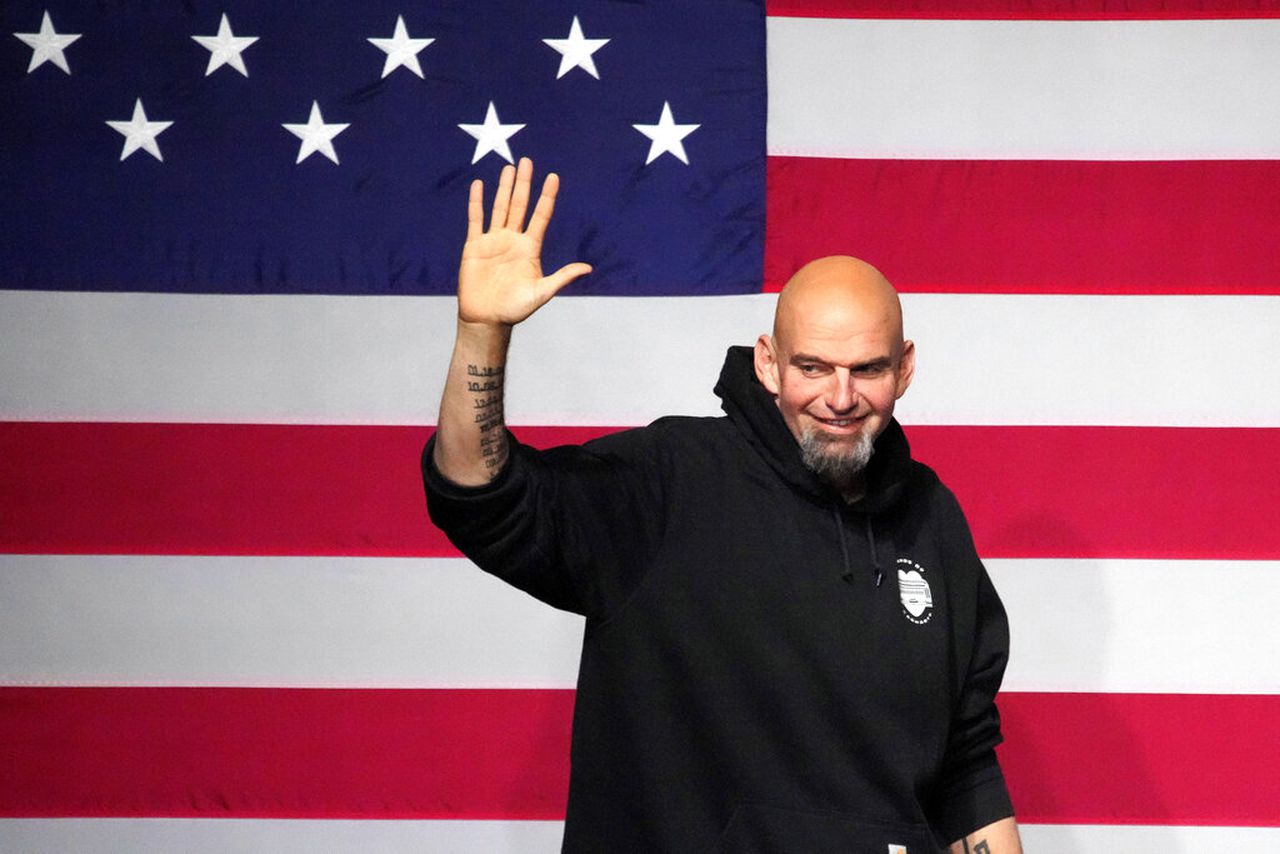

In a surprising move, the U.S. Senate recently bound itself to an official dress code, effectively ruling out flip-flops, T-shirts and hoodies on the floor of the Senate. That this even came up at a time when intramural disagreements among Republicans were about to shut down the government says a lot, but even so, let’s not forget how powerful and influential clothing really is.

“Clothes make the man” may sound like a mother’s advice to her young son to dress nicely while traveling, but it’s more than that. Your plumage announces who you are and where you fit into society.

Renaissance theologian Erasmus recorded the proverb “Vestis virum facit” more than 500 years ago. The saying and the sentiment are certainly older than that.

The outward marker of how you dress is something that you might do very deliberately, or you might do without considering what your clothing communicates to the world.

In a formal and deliberate way, military members wear the “uniform” of the day. The cut and style of the uniform, and the buttons and bangles that cover it, tell the world how the person fits into the organization.

The wearing of what our son, when he was a child, called “soldier clothes” goes back to the decorated belts worn by fighting men. While the dress of the Roman legions wouldn’t be up to the standards of 1950s Hollywood uniform perfection, you only had to look at a legionary to know who he was and what he did.

When Gen. Mark A. Miley retired as the nation’s highest ranking military officer the other day, he wore a uniform that tracked nearly half a century of service. More important, his boss — the president of the United States — wears no uniform. The president’s simple suit and tie communicate very plainly that the military is subordinate to the civilian control.

In America, we don’t demand special dress to appear in court. In a rejection of monarchy, the black and red robes worn by judges in England and her colonies were immediately rejected by American courts.

Still, striped pants and a cutaway coat were required to appear before the U.S. Supreme Court until the 1970s; and lawyers still dress in what we used to call “Sunday best” in all courts. (Their clients, unfortunately, sometimes don’t seem to get the message.)

But don’t believe that dressing to fit in is some old-fashioned notion.

Take concerts. When I was a child, I thought that when rich folks attended concerts or the opera, they always dressed in tails or gowns. Of course, my familiarity with such things was informed by old movies and cartoon depictions of the conductor waving his arms as the orchestra played. He was wearing formal wear — and in the movies, so was everyone else.

Now, though, dressing to a “form” of attire is simply out of fashion. Or is it?

If you were to attend a concert of the $uicideboy$ or some other punk act wearing a tailcoat or a long dress, you would either be marked a fashion leader or, more likely, a nut-job. Your “formal” attire wouldn’t match the attire for that occasion. Black T-shirts, ripped jeans, and lots of tattoos and piercings are the uniform for such concerts. You might not think of it as “formal,” but it is.

Fashion, of course, is a moving thing. What’s fashionable at one time is then passé, then eccentric, then daring and then, eventually, fashionable again. The return of bell-bottom pants and platform shoes was inevitable.

My father wore boxer shorts. My husband’s generation wears briefs, and my son’s generation wears boxer shorts. Chances are that my grandson or his sons will be back in briefs one day.

Whether we know it or not, we all react to how people dress. You may not think you’ll get better service in a restaurant and deferential treatment from people on the street because you are well-dressed and well-groomed, but you will.

We no longer have set dress codes for different classes. Anyone can wear purple now, not just royalty, and a woman can parade around in a red dress without being tagged as a prostitute.

The Senate taking time to discuss what kind of clothes to wear in our fractured and divided nation seems pretty silly. But although preserving the democracy should be foremost in their minds, how they dress is significant.

It’s significant for other people, too. Brides wear white, although most are not virgins these days. Wear a low-cut and backless dress to a business meeting, or shorts and a T-shirt to someone’s wedding, and see how you are regarded.

Mark Twain wore white suits in his later years. It was a mark of his brand of humor and wit. Mohandas K. Gandhi turned away from the Western suits of his youth and wore a simple Indian wrap-around dhoti. Roman senators were concerned with clothing; their white togas were rimmed with a purple stripe.

So, do clothes make the man?

Mark Twain’s fellow wag, author Thomas Wolfe (also frequently clad in white linen), answered the question well.

“Clothes make the man,” Wolfe said. “Naked people have little or no influence on society.”

Frances Coleman is a former editorial page editor of the Mobile Press-Register. Email her at [email protected] and “like” her on Facebook at www.facebook.com/prfrances.