Alabama’s Confederate mansions get state funding, distort our history

Monuments and statues are magnets for our attention, and Montgomery has its share.

But there’s something else I want to show you here.

Across the street from the Alabama State Capitol sits an old two-story wooden house with bright white clapboards and forest green shutters. A red, white and blue flag flies atop a pole out front, but it’s not the Stars and Stripes.

It’s the first national flag of the Confederacy.

This is the First White House of the Confederacy, and for a century this house has been a state-sponsored shrine to Jefferson Davis — never mind that Davis lived in this house for just six weeks.

And even then, he wasn’t here. This house used to be across downtown. Like the statue of Davis on the capitol steps, this thing was put here — moved to this block in 1921 — to deliver a message across generations. It’s a mission paid for by taxpayers and spelled out in state law: “the preservation of Confederate relics and as a reminder for all time of how pure and great were southern statesmen and southern valor.”

This is where Alabama still brings children by the busload to learn about the antebellum South and what the displays inside call the “War for Southern Independence.”

The first time I came here, as one of those school kids 35 years ago, I walked out carrying a souvenir Confederate flag. I’ve passed by it many times but haven’t gone inside.

Let’s go look around, but don’t sit on the furniture. In places like this, they don’t like anybody using a chair for a chair.

Since 1921, the First White House of the Confederacy has been a shrine to Jefferson Davis. By Alabama law, the state pays about $175,000 each year in operating expenses in addition to managing its employees. (Kyle Whitmire, al.com)

The first floor could be mistaken for a furniture museum — a desk used by Robert E. Lee, a rocking chair gifted by Zelda Fitzgerald. All that’s within reach is adorned with little white cards warning, “Do not touch.”

Most of the rooms are protected from intruders by iron gates or velvet ropes, except for one upstairs — the Relic Room.

The last bedroom of the Confederacy.

There, in glass display cases, are Confederate currency, a pocket watch Davis traded for a pair of boots when he fled to Canada, the last of three Confederate national flags …

But absolutely nothing about slavery.

Any mention is missing entirely from this place, like the detached kitchen left behind when the house moved. Like most antebellum museums in Alabama, this place tells a story of the people who lived here, but not a word for the people who worked here.

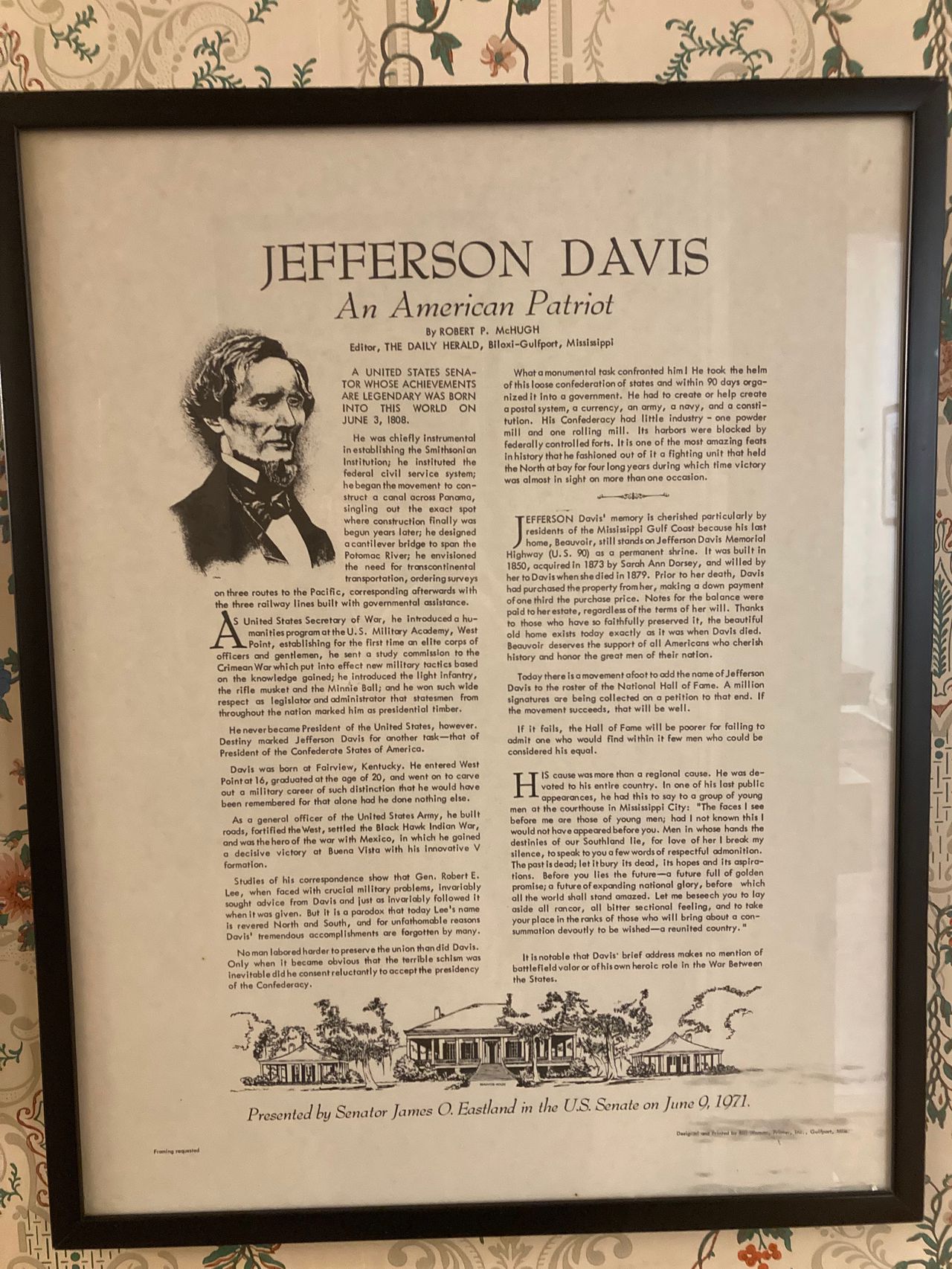

Instead, it portrays Confederate elites as enchanting heroes. Near the gift shop, there’s a framed newspaper editorial from 1971: “Jefferson Davis: An American Patriot.”

There’s also a box for donations.

“Since 1921, the First White House of the Confederacy is free to the public thanks to the White House Association of Alabama,” it says, referring to the local nonprofit that owns and manages the furnishings and the trinkets in the Relic Room.

That, too, is a partial truth.

This place isn’t free and most of the money doesn’t come from the White House Association. According to publicly available tax records, the foundation spent about $33,500 annually in recent years.

In that same time, the state of Alabama spent a little more than $175,000 a year here. By law, the Alabama Department of Finance manages the museum, its upkeep, and its employees.

This antebellum mansion is kept open by Alabama taxpayers, and it’s not the only one.

In the First White House of the Confederacy, you’ll find Confederate flags, currency and other memorabilia, but no mention of slavery. In the displays, the Civil War is referred to as the “War for Southern Independence.”Kyle Whitmire, al.com

No home for history

Across the country, monuments drew a lot of ire in recent years, but look around and you’ll find other anchors of Confederate nostalgia nearby — antebellum mansions converted into museums.

Unlike statues in the park, these things cost money.

House museums, as they’re called by preservationists, are not peculiar to the South, but here they come in a distinct vintage — full-sized Confederate dollhouses. Even after the Charleston massacre and the riots in Charlottesville, Confederate iconography and ideology have a home in these roadside attractions.

House museums are vessels for ideology, says Frank Vagnone, co-author of The Anarchist’s Guide to Historic House Museums.

“House museums are an attempt from the dominant culture to solidify a narrative that could be teachable to an audience that they said needed to be taught how to be American,” he says.

The state of Alabama owns and funds six antebellum museums, and gives out grants and legislative earmarks to others. City and county governments support dozens more, even in majority-Black Birmingham, which owns and operates the Arlington House.

Communities have inherited these institutions, like unwanted heirlooms, but few have had the will or the interest to develop them into something new.

So they keep doing what they’ve always done, however badly.

The possibility for something better is there. While visiting some of these sites, I would eventually find it — a Black Civil War reenactor who’s made preserving slave dwellings his life’s mission, a plantation heiress who joined forces with a rural Black mayor to open a space for reconciliation — but 150 years of cultural inertia won’t be overcome without effort.

It’s even harder when some of the people in charge of these institutions are often products of the institutions themselves – the generations who passed through places like the First White House of the Confederacy before anyone challenged the stories told there.

The folks who work in these old houses form attachments, Vagnone warned me, and the stories these old spaces tell can tangle with their identities. If you don’t show the proper deference, things can get uncomfortable quickly.

“These house museums are almost like churches,” he says. “They are places of community, and in many cases, they’re literally called shrines. They’re places of meditation and reflection, very much like a church. So when you start to question that, you’re questioning an almost core spiritual belief.”

Managed by the Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 308, the John W. Inzer museum has benefited from the political largess of state Sen. Jim McClendon, a member of the SCV Camp. McClendon said he couldn’t control whether people were offended by the Confederate battle flag flying out front.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

“Does that bother you?”

One afternoon late last year, I met a few of the folks he was talking about.

On a corner in downtown Ashville, Alabama, sits an old one-story wooden house with bright white clapboards and forest green shutters.

But this one flies a Confederate battle flag.

That flag might be the most recognizable icon of the Confederacy, but it was never an official national symbol of the rebel states.

The first time that flag ever flew over Alabama in any official respect was when Robert Kennedy paid a visit to Montgomery in 1963. Just before he got there, George Wallace had it hoisted above the Alabama Capitol, and there it stayed until Gov. Jim Folsom Jr. had it removed three decades later.

But here it still flies — a historically inaccurate flag at what’s supposed to be a history museum.

The John W. Inzer Museum isn’t only a house museum. It’s a clubhouse for the Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 308 and the local chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. That’s not a secret. It says so on the sign out front.

The museum is open by appointment only, which is fine. I’m here at the invitation of Alabama state Sen. Jim McClendon, a Republican from nearby Springville.

During the previous legislative session, a source told me to check out an unusual earmark in the state budget. As a member of the state Senate Finance and Taxation Committee, McClendon helps shape Alabama’s General Fund budget, and he’s made a place in it more than once for this little museum.

Last year, the Inzer Museum received $25,000 from the state of Alabama. And that’s not the first time the museum has seen a check like that. In 2015 it got $17,500 from the state and in 2011 it got $12,811.75. In 2009, it got another $22,500.

More recently, in 2017 it received $15,000 from the Coosa Valley Resource Conservation and Development Council, not the state, but when the local paper took a photo of the novelty check, McClendon was in the picture — with little Confederate battle flags flapping behind him.

This year the museum received another $25,000, only this time McClendon didn’t make the appropriation. Gov. Kay Ivey did it for him.

What makes these disbursements more peculiar is that the museum isn’t even in McClendon’s district.

He is, however, a member of Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 308.

“I’ve tried to help those guys out on a pretty regular basis, you know?” McClendon said when I asked him about it. “So what’s the problem?”

I asked him what folks should think about a state-funded museum with a Confederate battle flag flying out front.

“Does that bother you?” he asked.

It does, I told him.

“Well, it doesn’t bother me,” he said.

State Sen. Jim McClendon (right) has helped direct state funding to the John W. Inzer Museum in Ashville, Ala., a house museum run by the Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp 308. The museum flies a Confederate battle flag out front. McClendon is a member of SCV Camp 308. (Gary Hanner/The Daily Home)

Confederate causes have been a thing for McClendon in Montgomery, especially the state’s biggest such expenditure — the Confederate Memorial Park, near Prattville.

Last year, the state spent more than $670,000 there. Attempts to redirect those funds have hit resistance — primarily from McClendon who wields more power than just his influence on the budget. He also oversees legislative redistricting in Alabama.

“Everyone rallied around our Confederate History,” McClendon said after one attempt failed in 2009. “This was a sound enough defeat that it will echo through the chamber.”

I asked McClendon whether politicians should be deciding which historic preservation efforts get funding or if it should be left to professionals. He’s comfortable with lawmakers making those decisions.

“It just sounds like you’re trying to stir up — trouble,” McClendon said and ended our conversation.

But after we hung up, he called me again to offer an invitation.

That’s how on a brisk fall day, I got a personal tour, led by two Sons of Confederate Veterans and three Daughters of the Confederacy.

Despite briefly getting yelled at by the 87-year-old captain of SCV Camp 308 — who thought I wanted to destroy history — the visit was cordial and my hosts were kind.

The inside of the Inzer museum was dark. The red stained windows framing the front door, which were from Belgium and original to the house, cast little light until McClendon turned on a lamp. Jeannette Taylor, the chairwoman of the museum board, guided me room-by-room recounting the history of each artifact.

And each piece of furniture. Lots of furniture.

On the wall hung a lithograph of Alabama’s secession ordinance — which John W. Inzer had been the youngest and the last delegate to sign. Also on the wall are framed letters and proclamations from every Alabama governor since Fob James.

During the war, Inzer served in the Confederate army before being captured. While held prisoner of war, he kept a diary, copies of which the museum members handle with the reverence of a family Bible.

During the tour, I considered again what Vagnone had said — for their curators, historic house museums can be sacred spaces, antiques take on the significance of saints’ relics, and the stories that underlie the narrative become interwoven with the descendants’ identity, no matter how true those stories might be.

Most of us adopt the religions we are born into, and for the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Daughters of the Confederacy, the stories of their ancestors are something similar to religious beliefs. Expecting them to discard them can be like asking someone to remove their own appendix.

For most of my visit, I listened and cracked a few jokes to lighten the mood.

But after the tour, I did something I haven’t done yet in a historic house museum — I sat on a couch.

I didn’t hide from my hosts why I was there. I was trying to understand how Alabama wrestles with its history, I told them, and I want to show how that history influences our present.

The Sons and Daughters told me they are paying respect to their ancestors.

“I just like taking care of old things,” Taylor said.

I made the point that the flag outside is not historically accurate, and I asked them what message they think it sends to people who pass the museum, specifically Black people.

“Somebody can look at that — they draw their own conclusion to see that flag for what they think it means to them,” the captain said. “That’s a lot different than what it means to us.”

McClendon fell back on an argument I had heard before: Why are people so offended?

“If somebody is offended by something, whose problem is that?” he asked.

Of course, the trans-Atlantic slave trade is among the greatest crimes against humanity in modern history, and the Confederacy existed to defend slaveholding — just as it says in that Alabama secession ordinance hanging on the museum wall. If that’s not offensive, I don’t know what is.

But I wasn’t winning any converts.

Instead, I asked the group, when the day comes they aren’t here anymore, who will take care of this place?

McClendon said he worries about his family land, which has been passed down since before the Civil War. Will his granddaughter come back to take care of it? She seems to have a life of her own on her mind, he said.

The Inzer house is something like that, he argued.

“This group is proud of what they’ve got, and they’re spending their time and their money, their efforts on it,” he said. “If some offspring gets fired up, good. If they don’t — well, hell, — we’re going to be in the ground anyway.”

Until earlier this year, Evelyn England worked as a receptionist and guide at the First White House of the Confederacy. The museum should tell a broader story of history, she says. (Mickey Welsh/The Montgomery Advertiser via AP)AP

A job and a calling

George Washington’s plantation, Mount Vernon, is widely considered the first American house museum, but the largest wave peaked around the American bicentennial, Vagnone says. Since then, many have struggled to keep their doors open and few consider what purpose they should serve for the folks outside.

“History sites that were started decades and decades and decades ago, for one reason, are now being viewed by several generations later, dubiously questioning why they are there, what’s the narrative talking about?” he says. “Who’s been left out?”

Evelyn England will tell you, it’s people like her.

Until earlier this year, England was one of those state employees at the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery. There, she often surprised visitors.

England is Black. “I was the first, and for a great percentage of the time, for a long time, I was the only face that you saw,” she says. “So it didn’t bother me. If you could speak English, we can communicate.”

After 12 years working at the first White House, England quit this year after she refused to sign an employee performance review she felt had measured her work unfairly. She has since opened an EEOC complaint against the state.

State officials have declined to comment on her work history but released her personnel file pursuant to a public information request. That file shows years of positive performance reviews, a couple of suggestions for improvement and one formal reprimand.

England is a deeply religious person. When she first applied for a state job through the Alabama Personnel Department, she says she asked God for a challenge. When she saw the job she was matched with, she knew she had been given one.

“I was determined to hold up my end of the bargain,” she says. “I was going to give it my all until my all wasn’t enough.”

Near the gift shop, a framed copy of a 1970s newspaper editorial calls Jefferson Davis an “American patriot.”Kyle Whitmire, al.com

She believed it was important that people see her there.

And she needed a job.

“There was one lady, she asked, ‘How can you work here?’” England recalls. “She was with her husband. She was in the gift shop, and I said, ‘Ma’am, I’ll quit today if you pay all my bills.’”

England learned the details behind the furniture and walked guests through with enthusiasm.

I wasn’t the first to notice the kitchen was missing, she says. It was left behind when the state moved the building.

But it was the missing stories that bothered her more.

The museum gift shop she managed sold a book about a boy named Jim Limber, a Black child the Davis family took in during the war. Confederate apologists have seized on the story as proof Davis wasn’t racist, but England has her own theory after she compared pictures of Jim Limber to the other Davis children.

On a tour, she asked whether anyone noticed a resemblance.

That led to one of the few written criticisms in England’s personnel file.

“Some of the information about the Davis children had to be talked about so that the public did not get the wrong idea about the adoption,” one performance review says under areas for improvement.

England says she also caught heat for sharing her opinion of Davis’s marriage. Letters and other primary sources suggest that Jefferson and Varina Davis had a rocky relationship. None of that appears in the museum’s version of their life.

“I made the statement, and I think someone recorded me and took it back to the White House Association, where I said, ‘That was a marriage made in hell,’” she recalls.

Again she was told to stick with the approved story.

Another time, England was reprimanded for interrupting a conversation between two visitors to share her belief that buildings shouldn’t be named after people because all people have skeletons.

“As a Capitol Receptionist, you are to provide accurate information to visitors about the First White House and historical events, not your opinions,” her state supervisor wrote. “You have demonstrated that you are unable to present historical facts to the public so, effective immediately, you will no longer conduct tours or impart information concerning the First White House.”

England’s personnel file shows that, while she continued to meet expectations, her duties began to be pared away.

After the mass shooting in Charleston, the little Confederate flags in the gift shop, like the one I took home 35 years ago, were gathered up and stowed away, she told me.

“They said to pull it and I pulled it and inventoried it,” she said.

The Confederate story has been muted, somewhat, but nothing else has been let in to take its place or offer a broader view of history.

After 12 years, the small things added up, England said. She wanted what the museum denied for people who look like her — respect.

Dispirited, she said leaving the First White House behind felt like a personal failure. She’s come to love history, even when others take issue with her perspective.

“I’m not about eradicating anything,” England said. “On some points, I may be challenging your truth, but the doors of history need to swing both ways.”

At Magnolia Grove the state used a federal grant to restore a slave dwelling, but the museum is showing signs of neglect and on a weekday last year, it was closed for visitors.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

Something, but not enough

There’s a different history to be found than the one hard-coded into Alabama by the Daughters of the Confederacy.

But you have to know where to look.

I was told to go to the Black Belt, where the Alabama Historical Commission had tried to broaden what these antebellum mansions share.

Outside downtown Greensboro sits a two-story house. This one is brick but the front has been painted white. The shutters are forest green. From the road, the mansion can be hard to see through the magnolia trees.

Hence the name, Magnolia Grove.

This mansion is the oldest of five antebellum museums owned by the state and supported by the Alabama Historical Commission.

In the 1940s, the Hobson family donated this house with the state’s promise that their family could keep living there. The last of them, Margaret Hobson, died in 1978, and for nearly 40 years the state paid her a stipend to serve as a tour guide.

The Alabama Historical Commission owns the facilities, but in 2014, the state tried to shift responsibilities to what preservationists call “friends groups,” meaning local public nonprofits. The state retained ownership but the friends groups were given responsibility for operations, including managing museum collections and keeping the grass cut. An annual grant covers some of the costs.

The delegation of responsibility also distances the state from some of the choices made regarding the collections.

“We’ve put the daily operation in that community’s hands in the hopes that it gives the community more of a sense of ownership,” Commission site director Eleanor Cunningham told me later, regarding the friends groups.

The worst thing, she says, would be to mothball it.

So each year, Historic Magnolia Grove gets about $40,000 of state money, the least of the commission’s five house museums. At Confederate General Joe Wheeler’s former home, Pond Spring, the state has spent more than $900,000 over the last five years, or $107.75 for every visitor over the same period, according to state records.

When I approached the wide front porch at Magnolia Grove, the first thing I noticed was something green and black growing on the massive columns — mildew or mold, I’m not sure which. Maybe some of both. I didn’t touch it.

Instead, I tried the door knob.

It didn’t turn.

I knocked on the door.

No one answered.

In other state house museums, I had been greeted by receptionists who all seemed somewhat surprised to have a visitor.

This one was supposed to be different. But not like this.

What’s different was out back, in the crook of a treeline. There stands another house — tiny, with one door, three windows and no shutters. In front of the house, there’s a display on a post.

“Slave House, Who lived here?”

The sign was faded, clouded by baked-on dirt and cracked by the weather.

But this was something I hadn’t seen yet. Slave quarters are rare among antebellum house museums, at least in Alabama.

Almost a decade ago, the Alabama Historical Commission acquired a federal grant from the National Parks Service to restore this one.

But as every homeowner knows, a house is at constant war with nature, and here the elements are taking back lost ground. The same goo on the columns out front also stained the lower clapboards and ivy had begun to climb one corner of the house.

The door was locked, but through a window, I could spy a couple of wooden chairs, a small plain table, a fireplace and a museum display of Magnolia Grove’s census records, which include descriptions of people, each given a number, but no names.

Behind the mansion is a tiny house with two chairs, a table and a fireplace. Slave Dwelling Project director Joseph McGill brought a group here several years ago to spend the night, but since then, nature has begun to work again on the structure.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

Joseph McGill has been inside that little house and many others like it. The founder and executive director of the Slave Dwelling Project, he led a group here, not long after the quarters were restored, for an overnight sleepover.

Before founding the Slave Dwelling Project, McGill was a field officer for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and today he also works as a consultant for the Magnolia Plantation in South Carolina.

When I spoke with him later, he said the project grew out of one of his pastimes — Civil War reenacting. On his website, the headshot next to his bio shows McGill dressed in a Yankee blue jacket, buttoned collar and Union cap. Around campfires, he’s had conversations with folks in different uniforms who see that era quite differently. McGill is Black.

The importance of slave dwellings came to him in Amsterdam, he said, when he visited the attic where Anne Frank and her family hid from the Nazis. What his teachers in high school had tried to get across suddenly became real.

“When I went into that space, then it hit me — wow, this really happened in this space,” he says. “So that was kind of my epiphany, if you will, my ah-ha moment to know that spaces like that need to exist.”

Since starting the project, he has helped owners of old plantations and antebellum homes rediscover slave dwellings some had not realized were there — a storage shed or garage behind the house that had been there forever, or sometimes quarters in attics and basements.

His big idea was to take groups of people into these spaces overnight — to dwell. He thought it would be a one-year thing. Twelve years later, he’s still doing it.

“These spaces are not always positive, but the spaces still need to exist, because if they don’t, you will get those folks out on the fringe who are going to try to deny that these experiences, these errors, or these atrocities in our histories didn’t exist,” he says. “As you know, we do have some folks out there saying the Holocaust never happened.”

The Alabama Historical Commission restored the Magnolia Grove slave dwelling with a federal grant, but since then, the signage has cracked in the heat and fifth makes words hard to read.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

Slave dwellings can impart some sense of what slavery was like.

But that day I was stuck on the outside looking in.

I walked around the detached kitchen and knocked on the mansion’s back door.

Again no answer.

It’s a shame. There’s an opportunity here for something special.

In the middle of Alabama’s Black Belt, there’s a nascent renaissance happening. In recent years, Greensboro has seen an influx of outsiders attracted by the town’s cultural prospects and affordable real estate. Auburn University’s Rural Studio, south of town, has lent its attention to several sites nearby, including the Safe House Black History Museum.

The Safe House is where Martin Luther King Jr. once hid from the Klan while meeting with Civil Rights organizers. It has received some national attention as an atypical Black house museum, but not so much funding from the state.

Something is blooming here, just not Magnolia Grove.

As I drove away, I surveyed the Italianate and Victorian homes flanking the road. None boasted the same great columns, but their paint was fresh, the lawns were cut, and cars were parked in their driveways.

There were signs of life.

But the antebellum mansion behind me seemed embalmed.

Last month, the Klein-Wallace House hosted its third homecoming, when descendants of the enslaved and the enslavers return to meet one another and talk.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

No place for weddings

I thought that would be where this journey would end, but about a month ago, a colleague asked me to fill in for him moderating a panel at the David Matthews Center in Montevallo. It was there I learned of a Black mayor and white artist working together to give an antebellum plantation a new purpose.

So I invited myself to their party.

By Alabama Highway 25 just outside of Harpersville sits an old, wooden two-story house with bright white clapboards. The shutters used to be forest green but were recently painted a more modern slate gray.

This day people park in the grass and make their way through the front doors. From outside I could hear Nell Gotlieb’s voice above the others as she greets her visitors.

It’s Homecoming at the Klein-Wallace House, the third such event here that brings the plantation owner’s family and the descendants of their enslaved workers together.

Most of these house museums share a similar origin story: A stately manor falls into disrepair, a widow goes bankrupt or the children have moved away with no intent to return. Cheerful locals step in to rescue the structure before it turns to termite food. They fill the house with antiques and a story they prefer.

This one is different.

Gotlieb was the child who’d moved away, but she doesn’t want this to be a museum.

“We had the advantage of not starting until recently, and not having anything,” she says. “So we don’t consider ourselves a house museum and wouldn’t call it that.”

Born in Birmingham, Gotlieb left in 1962 with no intention of returning. She earned her Ph.D. in sociology and became a college professor in Austin, Texas. In her retirement, she shifted her attention to her art. Alabama was furthest from her mind.

Then her cousin called.

He wouldn’t be able to care for the family home much longer, he said. Would she take it?

Gotlieb was conflicted. She had good memories of the place where she spent summers with her grandmother, but she also knew what it had been.

The Klein Arts and Culture has dedicated itself to turning the Wallace House into a space for art and reconciliation, not another plantation house people can book for weddings.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

Thousands of acres of cotton fields surround the house. Those fields had once been her family’s property, too — as were the people who worked there.

Gotlieb returned to the house to take stock of what she’d been left. The house was sagging and the roof was beginning to cave. Bees had colonized a bedroom wall. It would need a lot of work, beginning with the foundation.

That’s when, she says, Theo Perkins drove up.

The Harpersville mayor is also a pastor and a school bus driver, and his connections give him something like social omniscience in the town, Gotlieb says.

“Theo just seems to know whenever someone’s at the house,” she says. “He knows everything that’s going on here.”

Perkins had come with a community concern. Gotlieb’s family owned a private cemetery about a mile away. Their enslaved workers had been buried there, too, along with generations of their descendants. The Wallace family had locked the gates and only allowed Black descendants to pay their respects once or twice a year.

“When I came and let them know how the community felt, the caretaker was here and they said cut that lock right now,” Perkins recalled.

Still, there was the question of what to do with the house.

It was Perkins’ idea to do something that would help the community, Gotlieb says.

Along with Perkins and other slave descendants, they came up with the idea to turn the house into something different — not a museum, but a cultural center for reconciliation and art. Together, they founded Klein Arts and Culture, which now owns and operates the house.

Harpersville Mayor Theo Perkins in front of the cemetery where his ancestors are buried. Perkins is a co-founder of Klein Arts and Culture, which is developing the Wallace House into a space for the arts in rural Alabama.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

The nonprofit has recruited a professor from Auburn University, Elijah Gaddis, to lead an interpretive task force. The working group is composed of history professors and specialists in museum studies. The majority of the members are Black and several teach at HBCUs.

“At its heart, it is an idea about how you interpret the past and what are the principles and approaches that you want to take to the past,” Gaddis said of their approach.

Those principles must be revisited regularly, first to ensure that the implementation is sound, but second to reconsider the principles themselves. This is what many institutions fail to do, he said, and how museums get stuck in the past.

“There’s an ideology behind the interpretation, and that ideology has often not been rethought in 20, 30, 40 or 80 years,” he said.

Gaddis said their plan will likely include what are called “shadow structures,” outlining where slave dwellings once stood, and outdoor artwork to decenter the house and its white plantation owners. Already, the foundation commissioned its first outdoor sculpture by Miles College professor Tony Bingham.

The interior of the house will remain in the state of what’s called “benign neglect,” Gaddis told me. It will tell its history by showing its age, not by being staged with antique furniture.

The board had no desire to turn the house into another Confederate dollhouse, Gotlieb told me. It won’t be another event space people rent for parties and weddings, as many house museums have done to get by.

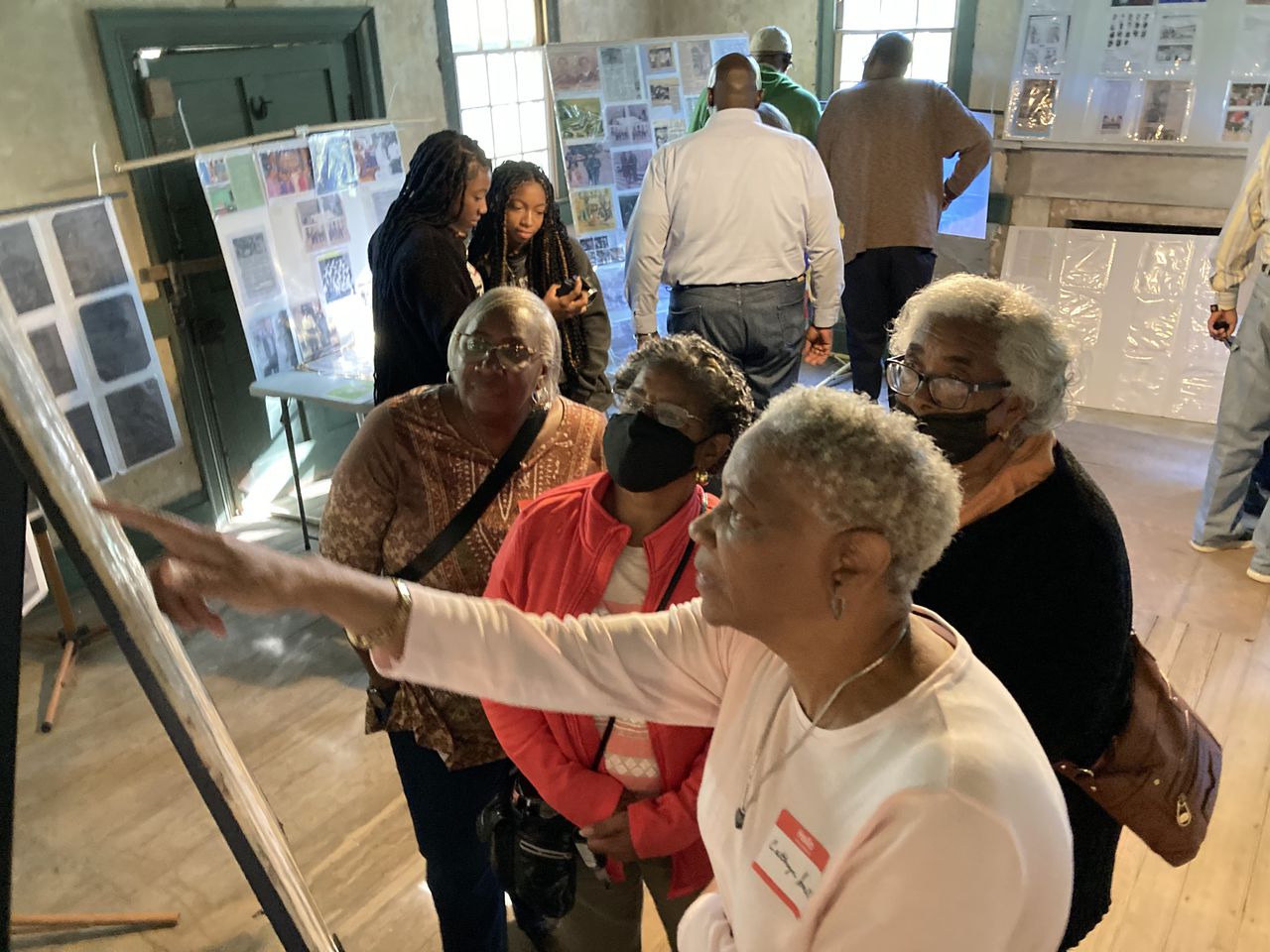

The Klein-Wallace House won’t be another Confederate dollhouse, but a space for reflection and creativity. At the Homecoming, descendants of the plantations enslaved poured over old records collected by board member Peter Datcher whose ancestors were enslaved on the plantation.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

In fact, years ago, the family had put all of their old furniture into storage where it later burned in a fire. She thinks that was a blessing.

So does Perkins.

“We never put anything in it because, we said, we want to fill it with the arts,” Perkins said. “We want to fill it with culture, we’re gonna fill it with the spirit of people that come there.”

At the homecoming, that included artwork by Bingham and large displays of local Black history ephemera collected by board member Peter Datcher.

Descendants milled about the room, poring over slave censuses and old school records, pointing at the pictures and whispering back and forth how they’re connected. Once all the families had gathered, everyone loaded into cars and buses for the mile-long drive to the cemetery, where the families laid a wreath, said a few prayers and sang Amazing Grace.

After the ceremony, Perkins showed me where his family members lay. He used to come here as a boy to help his grandfather cut grass, he said, and he feels like he’s always known its stories. Over there is an aunt murdered by the Klan, he said, and by that rock is his earliest ancestor, a great-great-great grandmother born in 1832.

During the ceremony, Perkins’s daughters had read the names of those buried here. And he watched them as we talked.

I ask him the same question I’d put to my hosts at the Inzer house: What did he hope for this place after he’s gone?

“The Wallace house becomes alive again,” he said.

Klein Arts & Culture co-founder Nell Gotlieb says her uncle put this wallpaper up in the 1950s. The organization intends to leave the house in a state of “benign neglect,” letting the building show its age. Shadow structures on the grounds will show where slave dwellings once stood and decenter the big house from the plantation’s story.Kyle Whitmire, al.com

So far this year, the house has hosted a performance by the Wideman-Davis Dance Company, poetry readings by local middle school students, and an overnight visit by McGill’s Slave Dwelling Project.

As Perkins and I spoke, the families slowly regrouped and returned to the old house. There, they gathered in the front parlor for an hour of conversation and fellowship before lunch.

On the parlor walls are a few shreds of old wallpaper, hung there in the 1950s by Gotlieb’s uncle. The pattern is of belles and gents riding horses in front antebellum mansions, larger and grander than this place ever was, like something out of “Gone with the Wind.”

“My grandmother hated that wallpaper,” Gotlieb says.

I can tell Gotlieb doesn’t care for it either.

But there’s not another antebellum mansion I’ve visited that doesn’t seem to try something similar — to paper over cracks, stains and rot with a romantic dream of the Old South, pining as her uncle did for a past that was never real.

What’s real is what’s underneath.

The past requires our attention, and it can’t stay hidden forever.

Kyle Whitmire is the state political columnist for the Alabama Media Group, 2020 winner of the Walker Stone Award, winner of the 2021 SPJ award for opinion writing, and 2021 winner of the Molly Ivins prize for political commentary.

Previously from State of Denial …

Alabama’s capitol is a crime scene. The cover-up has lasted 120 years.

Ambushed in Eufaula: Alabama’s forgotten race massacre

How a Confederate daughter rewrote Alabama history for white supremacy

Legislating while Black in Alabama: CRT and the struggle for respect