Meet Rodney Wilson, the gay teacher who championed National LGBTQ History Month

In the suburbs of St. Louis, Mo. in 1994, Rodney Wilson was a 29-year-old teacher of American history and American government at Mehlville High School. He realized that even his curriculum’s 800-page history textbook fell short of any queer history.

“That seemed to me a grave erasure of a group of people and their experiences, their movement,” said Wilson, the man behind LGBTQ History Month.

Wilson, of rural Missouri, is currently a Mineral Area College professor of American History and World Religions, and the coordinator of the History and Political Science Department.

Today, he wants LGBTQ history to exist outside of a closet.

January of 1994, Wilson drafted a proposal for a national LGBTQ History Month—with no blueprint on how to go about it. In fact, it wasn’t even proposed as “LGBTQ History Month,” but rather “Lesbian and Gay History Month.”

“We were not as conscious of the larger community in 1994,” Wilson admits. “We still had room to grow ourselves.”

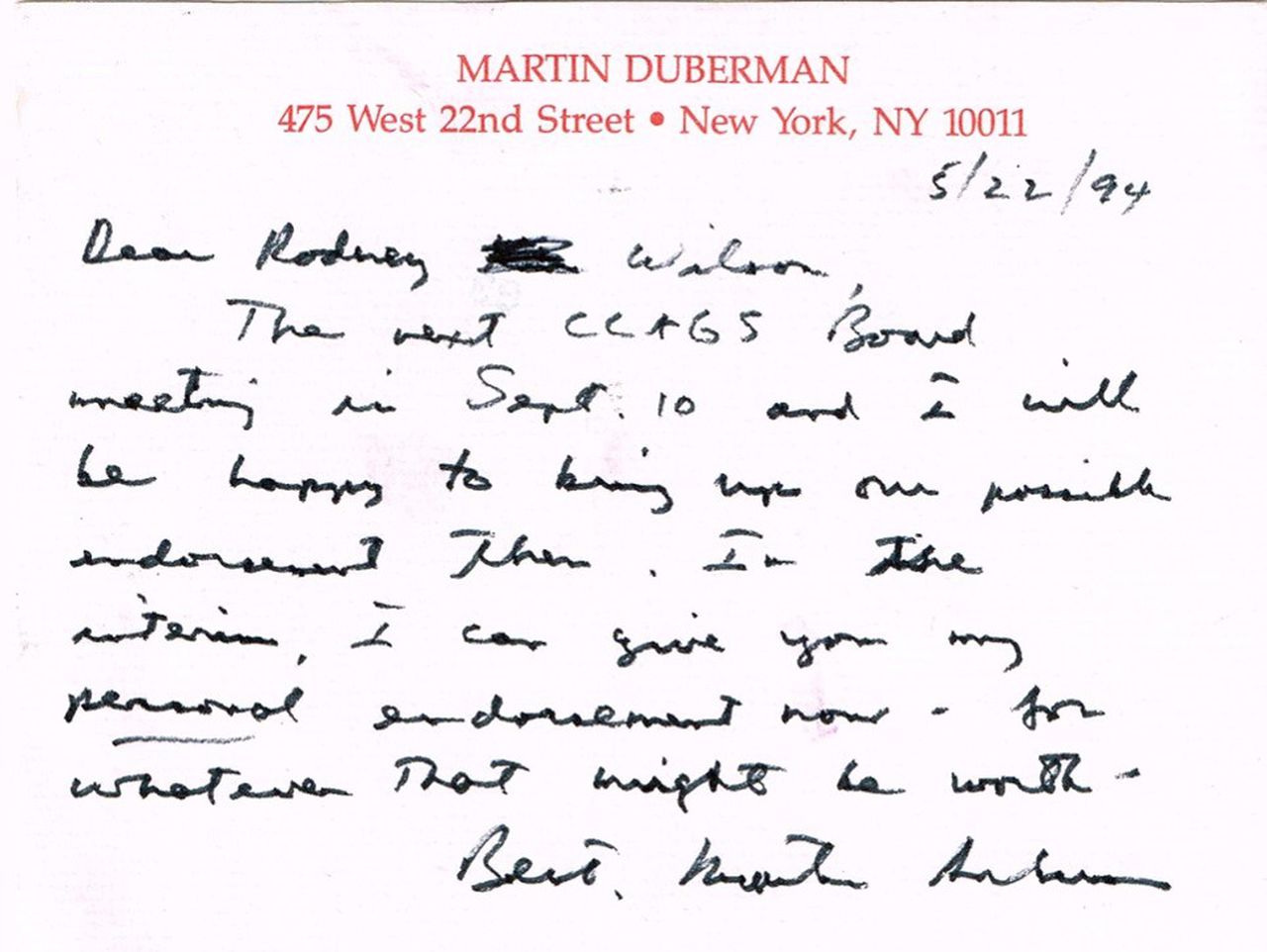

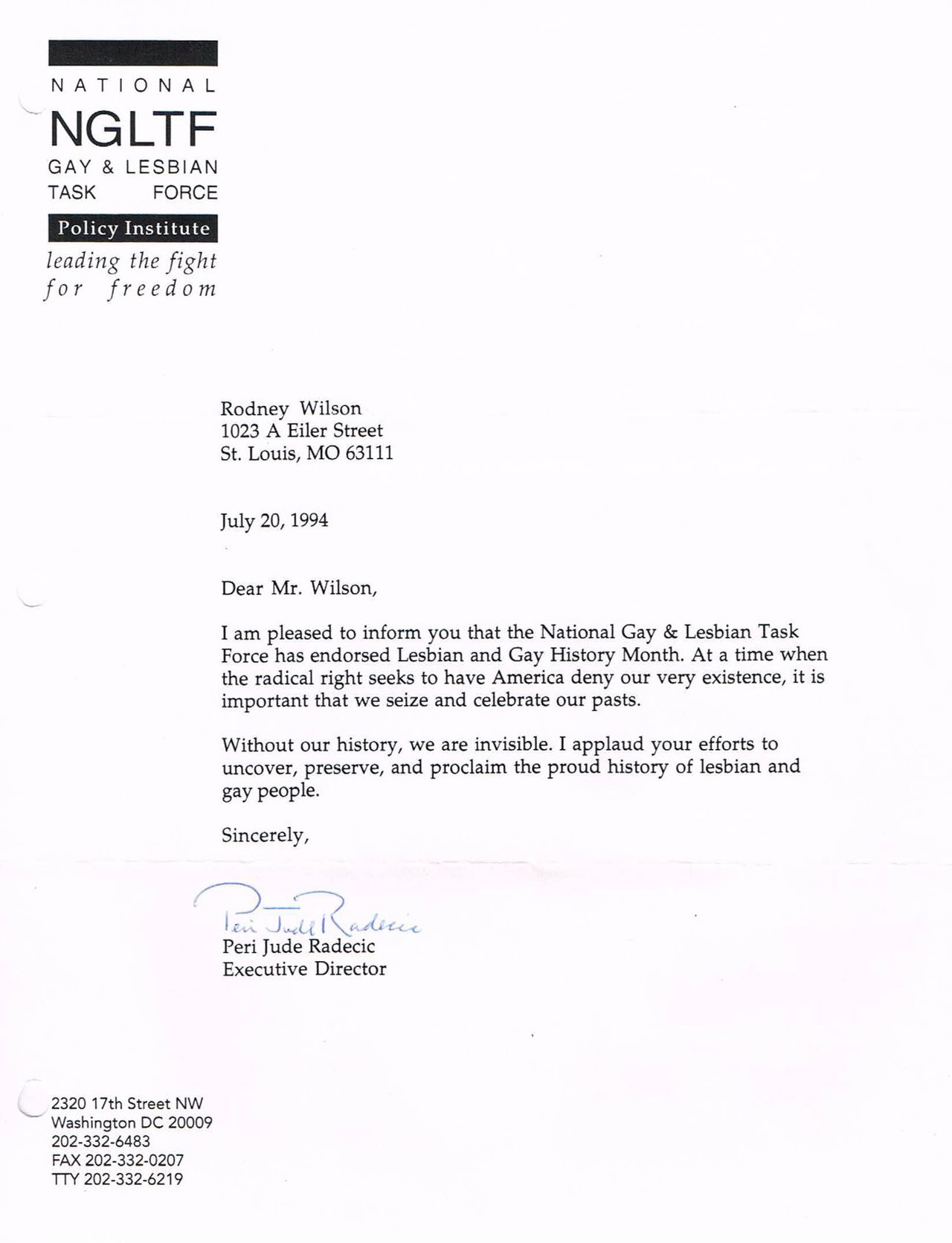

In the two-page proposal, Wilson wrote to the major organizations at the time to garner support. The recipients of Wilson’s pitch included GLAAD, Human Rights Campaign and what was then known as the National ‘Lesbian and Gay’ (now ‘LGBTQ’) Task Force. The organizations endorsed the idea, and Wilson’s organizing committee grew into a party of six, including the chair of the board of the Gerber/Hart in Chicago—then called The Midwest Lesbian and Gay Library and Archive—which became the institutional base for that very first year. Even from all the way in New York, fellow queer historian Martin Duberman wrote to Wilson, providing his own personal endorsement.

1995 May – personal endorsement of esteemed historian Martin Duberman. Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson

“We had to have our mainstream institutions in the LGBTQ community say, ‘This is a good idea; we’ll support it,’ because without that institutional support, you wouldn’t be able to create an event,” Wilson said.

1994 July from NGLTF, courtesy of Rodney Wilson

Earlier in March, during a lesson on posters, Wilson stood in front of his class and pointed to a pink triangle on one of the posters and said, “If I was alive during this time, I would be wearing this patch, because I am gay.”

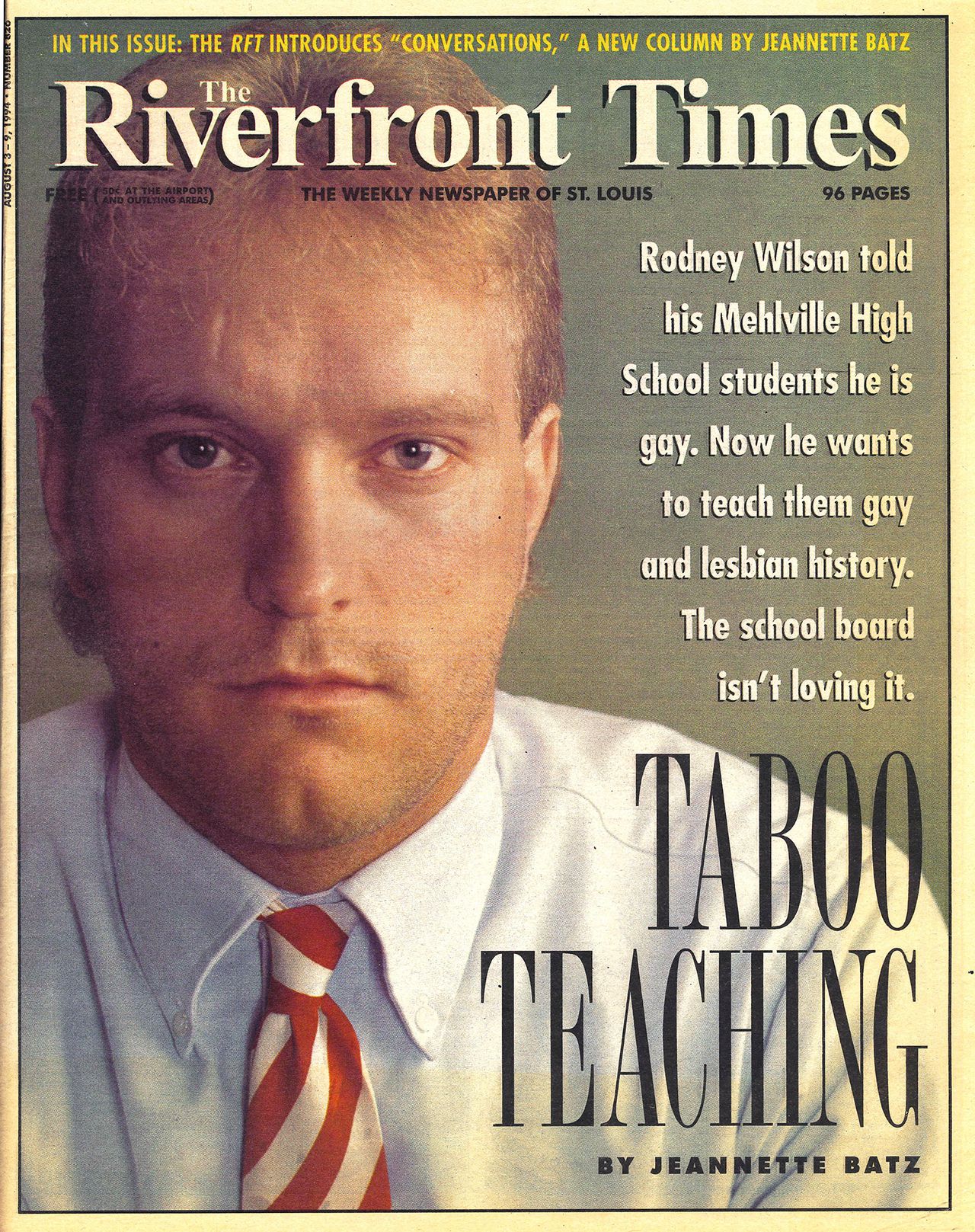

His coming out reverberated everywhere, even landing him a cover story on the Riverfront Times later in August—two months before the first annual National LGBTQ History Month. With that, Wilson’s was additionally attached to discussions over teachers’ disclosure of queerness throughout America.

1994.08-Riverfront Times. Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson

“In my high school of about 115 teachers, there were about a dozen of us who were LGBTQ,” Wilson said. “We knew each other, but we were all not saying anything about it when we were on the job, and certainly not wanting students to know about it.”

Wilson met his first openly queer teacher colleague during his first year of teaching. The colleague, twice Wilson’s age, was plugged into the community. That Christmas, he invited Wilson over to his house, along with the other LGBTQ teachers. He believed it to be important that, at the very least, conversation around queerness in school found itself out of the closet, and that we teachers acknowledge students who also might be queer.

“[LGBTQ students] have needs that sometimes are unique and different from the needs of the non-LGBTQ kids because they are a minority,” Wilson said. “They’re put on the fringes by society.”

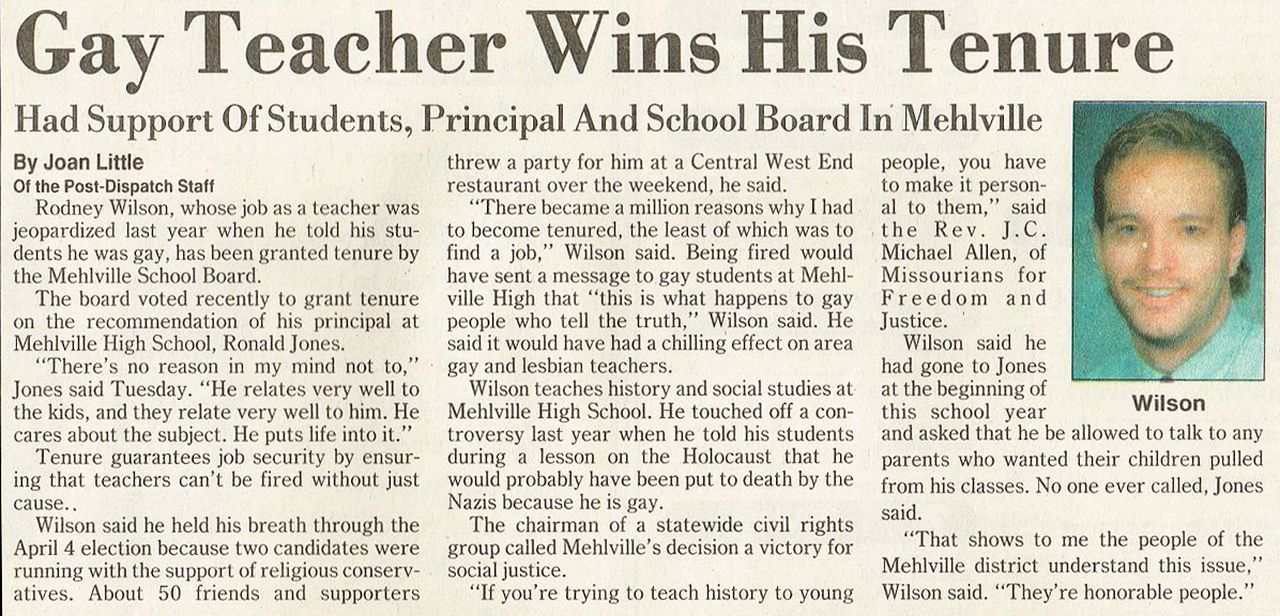

Tenure May 1995. Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson

Following President Clinton’s inauguration 1993, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was adopted to prevent U.S. LGBTQ military service members from being openly LGBTQ, sparking discussion over how much disclosure queer and trans people overall are to compromise. For Wilson, this translated as a desperate need to document history.

“I think there was a thirst for historical knowledge in the community at the time,” he said. “We all were looking for the lens of history through which to understand our current situation and place in the world and how we got there, and the things that we might do to advance where we need to be and want to be.”

Because Wilson intended for it to primarily be an academic celebration, he narrowed down the 12-month calendar to the academic calendar, in hopes it could be in curricula.

The option for August was out because school started in the middle of that month. September was the start of Hispanic Heritage Month, not to mention some schools don’t start until after Labor Day. November was Native American Heritage Month, and December was out because schools close for winter break until the middle of January. February was Black History Month, and March was Women’s History Month.

“April was a possibility, but by the end of the year, the last thing a teacher wants is one more thing to do,” Wilson said, chuckling. “In May, we leave for the summer.”

Outside of the academic year, October already had its own significance to the queer and trans community. The first March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979 was in October. The second March on Washington in 1987 was also in October, specifically Oct. 11—a date that would mark the inaugural National Coming out Day the following year.

Leading up to the first National LGBTQ History Month, a small curriculum packet was created, publicity press releases were issued, and members of the national council attempted to advance the proposal nationally. Meanwhile, local coordinating councils organized events in cities throughout the country—from St. Louis to Columbus, Ohio.

1994 July from GLA. Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson

The triumph of having started National LGBTQ History Month in 1994 Missouri was emboldened when LGBTQ people won a longstanding fight for gay marriage throughout the 2010s. Now, Missouri is reeling in a regression, having become the second state with the highest number of anti-LGBTQ bills—most of which attack trans youth. Wilson was under the impression that discussions over LGBTQ rights were well on its way to a final victory.

“It’s been very frustrating and sad to see the same arguments that were used against gays and lesbians in the 70s, 80s and 90s now be used against transgender people, drag, and nonbinary persons,” Wilson said. “I hate that we’re regurgitating that, and I hate that right now young transgender and nonbinary people are feeling the same angst, the same sense of attack against them that lesbian and gay young people were feeling 30 years ago.”

Wilson often recounts Mark Twain’s belief that “history always rhymes,” and that in human history, people take a few steps forward, face backlash, then they take a step back. He believes that future historians will see this as an example of demagoguery and how politicians scare people into voting for them, making them afraid of the ‘other.’

“Young people are teaching us all so much right now,” he said. “They have expanded the questions around gender, and sexuality, and they’re teaching people like me, too. I’ve been in this community a long time; I have things to learn because I’m almost 60 years old. [I wish] we would allow this learning to happen, instead of being afraid of it, instead of calling it bad, instead of shaming young people.”

Outside of Missouri, LGBTQ History Month grew internationally.

In September 2021 at the Florence Queer Festival, a group of radical historians and activists announced they were bringing LGBTQ History Month to Italy in April 2022. It became the first of its kind in southern Europe. Two months later, nineteen representatives, including Wilson, met via Zoom and officially co-founded the International Committee on LGBTQ+ History Months. Representatives met on behalf of Australia, Berlin, Canada, Cuba, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Scotland, UK, U.S., Wales, and even ASEAN SOGIE Caucus, which LGBTQ people in ten Southeast Asian nations.

2022 – current history months. Photo courtesy of Rodney Wilson

Wilson believes that he was born disconnected from society, especially when he realized he was gay at 8 years old. To ground himself, he delved into history.

“History is a stream, and we all step into it when we’re born and we step out of it when we die,” he said. “I stepped into that stream at a time in history in which I couldn’t find other people swimming around me who were like me. Family history, American history, world history and LGBTQ history empowered me, and helped me come out completely to myself, accepting myself as who I am.”

For Wilson, history at its core is mystical, particularly “about this continuing conversation with the dead, and with the events that they worked on and completed in their lifetimes—some of which are still with us, and some aren’t. There’s a real mystical communion between the past, the present and the future in studying our history.”