From Stonewall to RuPaulâs Drag Race, this book gives the full, rich history of drag in New York

New York City sidewalks, when hit with a certain light, shine like glitter on concrete.

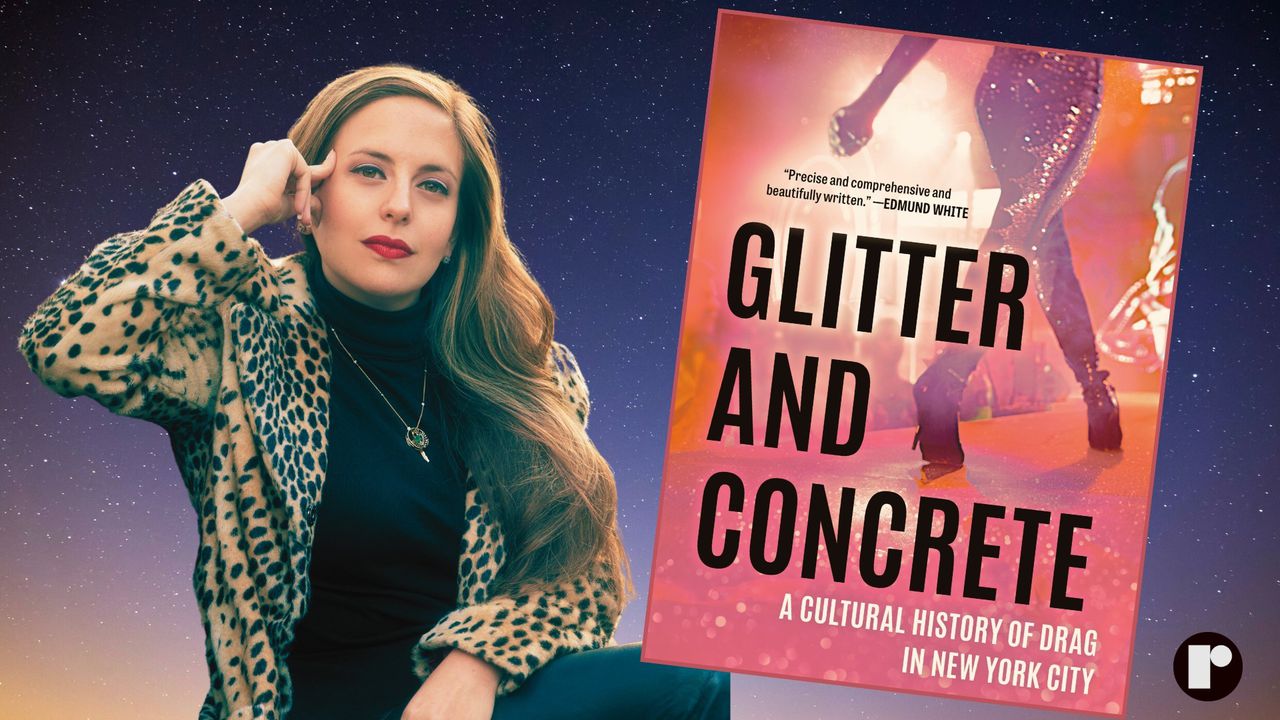

That is, according to Elyssa Maxx Goodman, author of Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City, which was released on Sept. 12. Her debut book is a historical dive into the art of drag in New York City, drawing research from 1860 to present day.

The prologue of the book illustrates the glamorous walks of life that occupy the streets of New York, and how there is a glimmer when the light hits the concrete just right. Goodman draws the connection between the sparkles of the street to the way drag shines light on our everyday life. But the title of the book isn’t “Glitter on Concrete”—the “and” in the book title is vital because the relevance of drag relies on the world that exists outside of it.

“If “glitter” is drag, then “concrete” is anything that’s not drag,” Goodman said. “For me, drag rises out of this otherwise normal everyday life, and it sparkles in ways that normal everyday life doesn’t. Drag is extraordinary, and you can see that when you look at it. You need the concrete so you can see what sparkles.”

The book’s chapters are sectioned by decades, though the first chapter is vast, spanning from 1865 to 1920, delving into lives like Andrew Tribble’s. Born in Kentucky in 1876, Tribble, like many other Black performers, came into the world of female impersonation—a term defined by the people at the time—in order to elevate Black talent at the turn of the century, touring across the country including New York City. Besides the fact that many minstrel troupes were headquartered in the city, Black performers participated in blackface as a way into the industry.

Goodman’s findings also recount Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the late 60s leading up to The Stonewall Riots, as well as 90s vignettes of Zaldy Goco, a Filipino American artist who appeared in a controversial Levi’s commercial in 1995 in feminine glam. Later on, he became RuPaul Charles’ key fashion designer, which is still true today.

Despite the wide range in time and richness of historical retellings, Goodman classifies Glitter and Concrete as an introduction to drag.

“There are other cities that have very rich drag history—San Francisco, Houston, Atlanta, Miami, Chicago,” said Goodman, whose book is mainly centered on New York. “If this book can function as a way to get people interested in those places as well as New York, then by all means. I just want it to inspire interest in drag history in any form.”

The cultural significance of drag is not new to Goodman, who was a freelance contributor at the national LGBTQ magazine them for years as a drag historian. Goodman also works as a photographer, having shot the cover of Glitter and Concrete herself at a drag show—one of hundreds of drag shows she has attended. Having freelanced since February 2011, she also runs a monthly free public reading for writers, curating each show under her own literary drag persona, Miss Manhattan, for the Miss Manhattan Nonfiction Reading Series. Her reading series will be 10 years in the running by next April.

“I’ve written about everything, from gay motorcycle clubs to Jello, and it makes me so happy,” Goodman said, doting about her love for the art of nonfiction, which she classifies as the “glitter” on the “concrete” of other genres. “The thing that I’ve always wanted to do with my writing is to share stories about the lives that we don’t hear about. Whenever there’s an opportunity for knowledge, the opportunity for fear decreases.”

Despite Goodman not being queer and not working as a drag artist, one might question her relationship to the drag community—especially when it comes to earning trust from sources she reached out to for Glitter and Concrete. But her body of work at them and her own personal love for drag transcended into meaningful interviews that led her to even more valuable and hard-to-get sources to share their stories with her. And as a photographer, Goodman understands firsthand what it means to be a witness in the spectacle of drag.

Given the onslaught of legislation against drag today, Goodman, in preparation of the book, was already privy to zooming in on the politicization of the artform over the course of the 200 years that spans in the book.

“This has been happening throughout drag’s entire history, and it runs in 10 to 15-year cycles,” she said. “And that’s the thing that is incredible about drag; despite this fierce backlash that happens in these waves, this art form has perpetuated for thousands of years. I don’t think there are other artforms that experience that in the same way.”

Looking ahead, she’s excited to see drag that further blur gender binaries. “Not just male or female but drag that drags the nonbinary [identity] as well,” she said, describing nonbinary people doing drag as “luscious.”

Above all, Goodman feels optimistic about the fight for LGBTQ rights overall, noting that there are major differences between the artform of drag from hundreds of years ago and today.

“There is support for drag from mainstream culture, and it’s not just the queer community that’s fighting the backlash,” Goodman said. “And because there’s a larger understanding of queer rights as a necessity for people, the fight has more allies than it ever has. The other part is that there’s also support for drag from within the queer community itself.”

Although the pulse can be felt throughout the expansive time traveling journey Goodman takes the reader on, the root of Glitter and Concrete’s heartbeat, ultimately, lies in its first few pages. From falling in love with drag from watching To Wong Foo at seven years old, and having been catalyzed by the death of drag icon Flawless Sabrina in 2017, Goodman has dedicated a world of history within New York City to preserve the beauty of drag.

Glitter and Concrete teaches every reader that like glitter, there is a life and shine to drag when, beyond the artificiality, imagination meets generosity. In that crux, drag can make everyone, like Goodman, think: “There’s nothing more real.”