Guest opinion: Alabama legislators are on the wrong side of history

This is a guest opinion column

When I was 13, my father was sentenced to 60 years in prison. I was a kid, but I knew the sentence was unjust. Even then, I knew that his race and class unfairly influenced his sentence. As a young teen, I vowed that I would spend my life advocating for marginalized people.

The very next year, I started as a page in the Alabama Legislature. I was in the program for six years. While serving as a page, I had the opportunity to watch legislators work on criminal justice reform. From the time of his incarceration to the time he came home, I engaged and met with legislators, lobbyists and department heads urging them to release my dad due to his unfair sentencing. Due to that work he was released in 2016, after serving just nine years. His experience fueled my passion for justice and my determination to stay engaged.

My advocacy is bigger than my family of origin; other people suffer under the weight of injustice. That is why I was motivated to become a plaintiff in Milligan v. Allen, Alabama’s historic redistricting case. Having served as a Community Redistricting Organizations Working for Democracy fellow with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, I was paired with Alabama Forward and worked on its democracy program. Today, I am on Alabama Forward’s staff and work as a chief field campaign strategist. In this capacity, I focus on redistricting, or the drawing of legislative lines. And few things are as important as redistricting.

Redistricting ensures that communities can participate in democracy and elect candidates of choice. How ironic that this case is in the state of Alabama. If there is a ground zero in the fight for voting rights, it is in Alabama. Alabama was home to docking slave ships and then centuries later the Montgomery Bus Boycott; freedom rides; and, of course, historic marches for voting rights. Civil rights workers were beaten, maimed and killed in Alabama so that those in and out of the state could participate in our nation’s democracy. The community gave so much, and yet some elected officials are willfully choosing to ignore not only our place in history but our responsibility to preserve democracy.

Those in Alabama and those who are part of the movement for racial justice consider Alabama the birthplace of civil rights. The reason the nation enjoys voting rights is because of the struggle and sacrifice of many Alabamians. This is a rich legacy to live into, but we cannot allow the state’s leadership to choose an alternate, more sinister path.

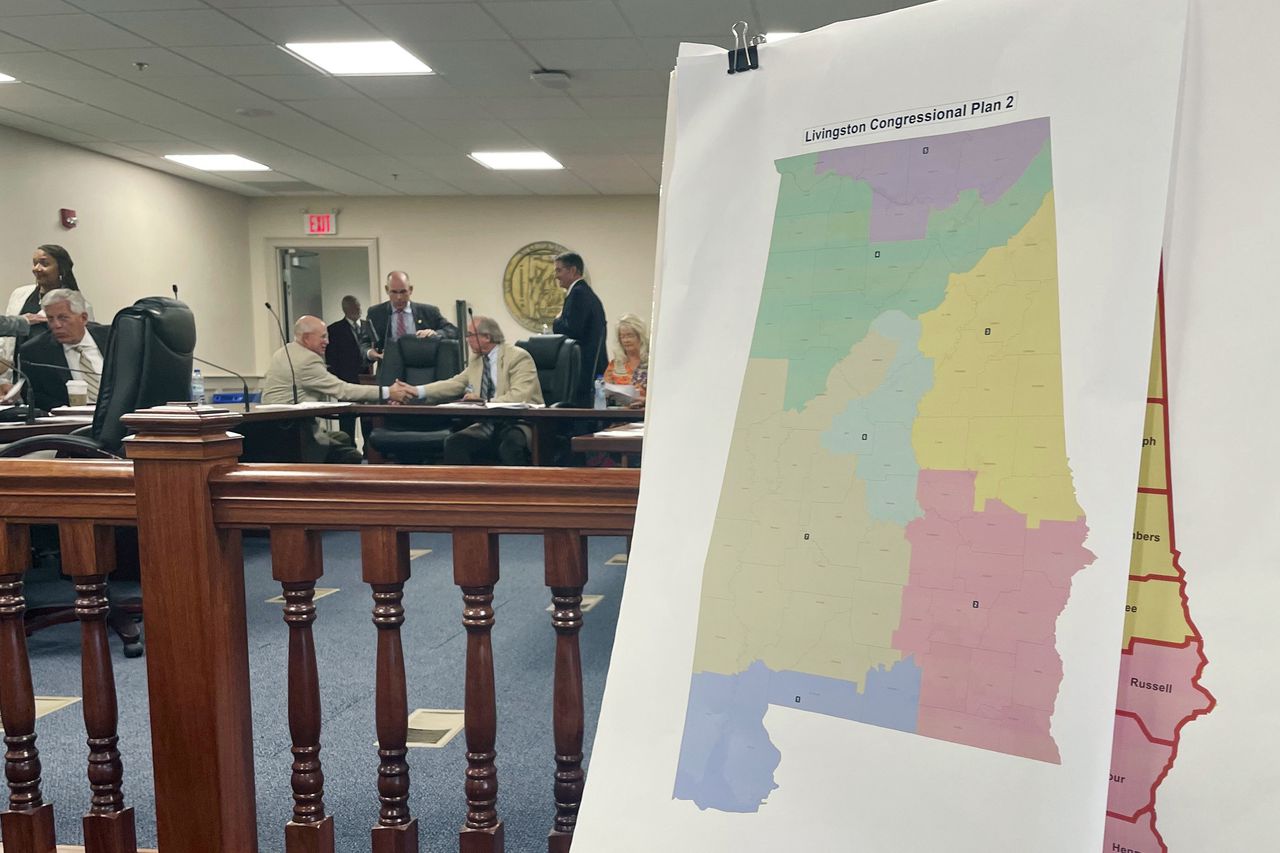

When the U.S. Supreme Court directed Alabama to create two majority-minority districts, it did so because it knew that all voters have the right to elect candidates of choice, and Alabama’s current lines eliminated that right for Black voters. The court ordered the Legislature to draw two majority-minority districts, and it drew one. The second district the Legislature drew is only 36% Black voting age population, and the white voting age population is 64%. It left the overwhelmingly white voting age population intact, which will enable those voters to elect their candidate of choice. The current maps make it impossible for Black Alabamians to choose their preferred representatives – they’d need representation of over 50% to elect candidates of choice.

The court issued its ruling, and now it’s up to citizens to make the state comply. We must hold elected officials accountable. Elected leaders in our state ran for office on a promise to represent all constituents, and that includes Black and brown voters. We cannot let them off the hook or allow them to manipulate voting lines in a way that disenfranchises the descendants of activists who fought for freedom.

Although some Alabama policymakers are on the wrong side of history – opposing equal representation – our communities cannot let them operate with impunity. This is not the first time our communities have faced recalcitrance from elected leaders, and it won’t be the last. We must stay engaged and abreast of what’s going on and commit to always raise our voice. If my own story has taught me anything, it is that we are never too young to get involved and fight for change.

Khadidah Stone is a fellow with the Black Southern Women’s Collaborative.