Aging population needs culturally competent care

Editor’s note: A different version of this story originally ran in India Currents. This report was made possible in collaboration with palabra and Altavoz Lab, a project created to support community journalists investigating public accountability on behalf of immigrant communities, Latinos and other populations not sufficiently covered by major media.

By Meera Kymal and Anjana Nagarajan-Butaney

In 2005, Tahera Khalil suffered a heart attack while she and her husband Sabbar were visiting their daughter, Nishrin, in California. Worried that she could not care for her aging parents if they returned to India, Nishrin urged them to remain in San Jose, where she lives.

Tahera and Sabbar stayed, but they did not anticipate the consequences of growing old in a country without universal healthcare.

Today, 18 years later, the Kahlils live in a senior community less than three miles from Nishrin’s home. Sabbar, now 95, suffers from macular degeneration (an eye disease that causes blurred vision) and the side effects of radiation after a bout with cancer. As his eyesight fades, he’s increasingly dependent on Tahera. Sabbar doesn’t yet meet the criteria to receive skilled nursing care, but as his health issues become more complex, the burden on Tahera grows.

At 88, Tahera recently had a pacemaker fitted but continues to manage the cooking and housework with Nishrin’s help. The Khalils cannot afford private caregivers. Nor would they move Sabbar to a nursing home even if he qualifies for it, especially not to one that lacks culturally congruent care.

“I can take care of myself and my husband,” says Tahera steadfastly.

In many immigrant families, aging in place in a multigenerational setting is the cultural norm. Nishrin’s abiding commitment to helping her parents is typical of her South Asian roots. But as aging takes its toll on the elderly, family members are left to perform complicated caregiving tasks without support or training, thus placing their own health, finances and well-being at risk.

This trend reflects a nationwide exigency. As more people in the U.S. live longer, a higher prevalence of chronic diseases — ranging from arthritis and chronic pain to hypertension, diabetes and dementia — will fuel the demand for support services.

America is graying

Approximately 56 million adults age 65 and older live in the U.S., according to 2021 data from America’s Health Rankings, representing just under 17% of the nation’s population. The year 2030 marks a demographic turning point for the country; that’s when all baby boomers will be older than 65. Put another way, one in five Americans will be at retirement age.

The U.S. Census predicts this demographic will reach 77 million by 2034, with older adults outnumbering children for the first time in U.S. history.

Seniors 85 and older — the group most often needing help with basic personal care — will more than double between 2020 and 2040, says an Urban Institute study.

Projections show that Latinos age 65 and older (about 4.6 million in 2019) will grow to just under 20 million by 2060, an increase from 9% to 21% of the older U.S. population.

As the ethnically diverse, aging population grows, so will the demand for culturally competent services to address their growing healthcare needs.

Nishrin Khalil, daughter of Tahera and Sabbar Khalil, greets a family friend on a video call. Nishrin visits her parents everyday. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

More long-term care needed

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHSS) estimates that at least 70% of people over 65 will need some type of long-term care as declining cognitive and physical health impairs their ability to function independently.

In Santa Clara County, California, 18% or 342,000 of the state’s 1.9 million residents are older than 60, an age group predicted to triple to just over one million by 2030. A study by the Public Policy Institute of California projects that this growing population will face significant difficulties with self-care.

Santa Clara County — which includes San Jose, where the Khalils live — is already estimated to have as many as 52,000 senior residents who will require long-term care. The county delivers home-based services to older, low-income residents through Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program), but it lacks the infrastructure, manpower and funding necessary to fully support a rapidly growing elder population who will live longer with chronic conditions, fewer family caregivers and shrinking savings.

Santa Clara County’s quandary is a microcosm of what’s happening across the nation.

Intergenerational care, duty and honor

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines “intergenerational caregiving” as the hands-on care undertaken by adult family members for their aging parents. In the U.S., that support pool now stands at 41.8 million.

According to Vivian Nava-Schellinger of the National Hispanic Council on Aging (NHCOA), in Hispanic cultures, caring for aging parents is simply an ingrained cultural value of duty and honor. Family members in multi-generational households offer intergenerational care “for aging parents, relatives or family members without ever identifying as a ‘caregiver.’”

This family dynamic is the norm in many U.S. immigrant households. Nearly 60 million residents live with multiple generations under the same roof. A 2021 Pew Research Center study reported a growing trend in which a higher share of foreign-born Americans (24% of Asians and 26% of Hispanic immigrants) were more likely than white Americans to live in a home that includes grandparents.

Family circles of care

In Mamaroneck, NY, Lilian Pérez’s 93-year-old father-in-law, Doroteo López, suffers from early-onset dementia. Over Christmas last year, Doroteo fell and was hospitalized. His physician suggested a nursing home for his post-admission care. But the family wouldn’t consider it. They were alarmed by the negative experience of an elderly family friend at a nursing facility earlier that year.

Doroteo López with his daughter, Onilia, on his 90th birthday. Photo courtesy of Lilian Pérez

Doroteo’s adult children now follow a rotation where each takes a turn caring for their father overnight. In the daytime, from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., a licensed, Spanish-speaking home care aide looks after Doroteo’s needs.

“He’s never alone,” says Lilian.

The family found a culturally competent, Spanish-speaking aide through their large Guatemalan community. New York State Medicaid covers the aide’s costs because Doroteo qualifies for in-home care.”We prefer to have him home,” says Lilian firmly. “You know, we are so attached to our people.”

The Khalils share similar strong familial bonds. Cultural ties to India shape their religion, food and family relationships. Nishrin calls her mother “her rock and best friend!” Nishrin, her husband, Khaled Hasnat, and her brother Nazir, form a circle of support to enable Tahera and Sabbar to remain in their home.

Both families mirror a trend across the nation reported by AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons), where 1 in 5 Americans provide intergenerational caregiving for aging parents. The Pérez-López family fits the profile of the “Typical Hispanic Caregiver” whom AARP describes as caring for a parent or in-law over 65 in high-intensity care situations and who feels their role gives them meaning and purpose in life.

Caring for a parent “is part of our lives,” says Lilian Pérez. “We grow up that way, generation to generation.”

This intergenerational setting works as long as seniors in the household are fit and able. But as they grow frail and develop health issues, undue burdens strain the most dedicated of families.

Looming gaps in care

To age in place in San Jose, the Khalils need assistance with the business of daily living. AARP defines this as routine tasks like bathing and dressing, preparing meals, maintaining finances, keeping medical appointments and managing medications.

Like many regions across the country, Santa Clara County faces widening gaps in home-based services for its increasingly diverse and rapidly aging population. Almost 40% of its residents are foreign-born. Two of its largest ethnic groups are Asians at 37.4% and Hispanics at 25.1%. Eligibility limits, high costs and a shortage of trained caregivers woefully undermine the effectiveness of services the county delivers to seniors, causing a caregiver crunch that curbs independent living.

“In Santa Clara County, there’s going to be very few people who are going to be receiving long-term care through Medicare,” says aging expert Bob Brownstein of Working Partnerships, which assesses the county’s health services.

“Some very affluent people are able to pay for it,” he adds, “but really what happens for people who are middle income is they spend [down] their assets to become eligible for Medi-Cal. This population can live comfortable lives if they get decent, long-term care. But the political system hasn’t gotten there to be able to treat that with the urgency that it needs.”

Sabbar Khalil’s medications stay on the family room table for easy access. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

High costs of care

According to AARP, Latino families spend less per year ($7,167) than whites ($7,300) on caring for aging loved ones. But the financial strain is greater “because it represents almost half the income of Latino caregivers,” states AARP’s report.

Before her in-laws qualified for NY state Medicaid, Lilian Pérez’s extended family — her husband Abraham López’s seven brothers and sisters —pooled their resources for a private, in-home caregiver, paying $40 per hour for seven to eight hours daily for eight years to care for her ill mother-in-law.It costs over $20 an hour to hire a home health aide in the San Jose metropolitan area, reports Working Partnerships.

San Jose resident Jaya Padmanabhan paid a private agency $2,500 to $3,000 a month for a qualified aide to provide three to four hours of care a day for her 88-year-old mother, who was diagnosed with early-onset dementia.

“Hired help doesn’t come cheap. Each time you press a button to ask for additional help, it comes with a price tag,” says Padmanabhan.

When she couldn’t manage anymore, Padmanabhan made a heartbreaking decision to place her mother 3,000 miles away in a nursing home in Chennai, India, where she would get more affordable, culturally congruent care.

Doroteo López is carried to the bathroom by his grandsons, Joshua and Jesse. Photo courtesy of Lilian Pérez

Systems of care failing

More seniors will rely on paid caregivers provided by home care agencies, reports Working Partnerships. As a microcosm of what the rest of the nation will face, California will need as many as 3.2 million additional care workers by 2030 to fully meet demand. But it faces a trained caregiver shortage.

Santa Clara County provides in-home care services (IHSS) only to people who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or who meet all Medi-Cal income requirements. Qualifying for care can be daunting.

The Khalils had to pass a stringent two-step evaluation of their income and service needs before qualifying for a cleaning aide. Any additional care requires another re-evaluation, adds Tahera.

“I have not been able to connect with my social worker for quite some time. The social worker used to come every year,” she says. “We spoke to the person in charge, and she said that they have too big a load.”

The county’s social workers are overstretched, admits IHSS manager Terri Possley, with each social worker handling 350 cases. “They’re overburdened with cases. We don’t have enough social workers.”

Home care aides don’t stick around either because they are poorly paid, says Bob Brownstein. Home health and personal care aides earn between $28,000 to $36,670 per year.

Without a safety net, the majority of older adults in Santa Clara County and elsewhere lack home-based coverage. The problem will only get worse as the aging population grows.

Medicare and commercial insurance plans do not cover long-term care. The exorbitant costs of long-term care insurance mean that almost 90% of Americans don’t have any, reports Stateline (previously with the Pew Trust), because people worry that fluctuating premiums could wipe out their savings.

“From my personal point of view,” says Working Partnership’s Bob Brownstein, “it’s crazy to tell people they have to impoverish themselves before society will help them deal with long-term care, which is increasingly a problem that impacts very, very large numbers of people.”

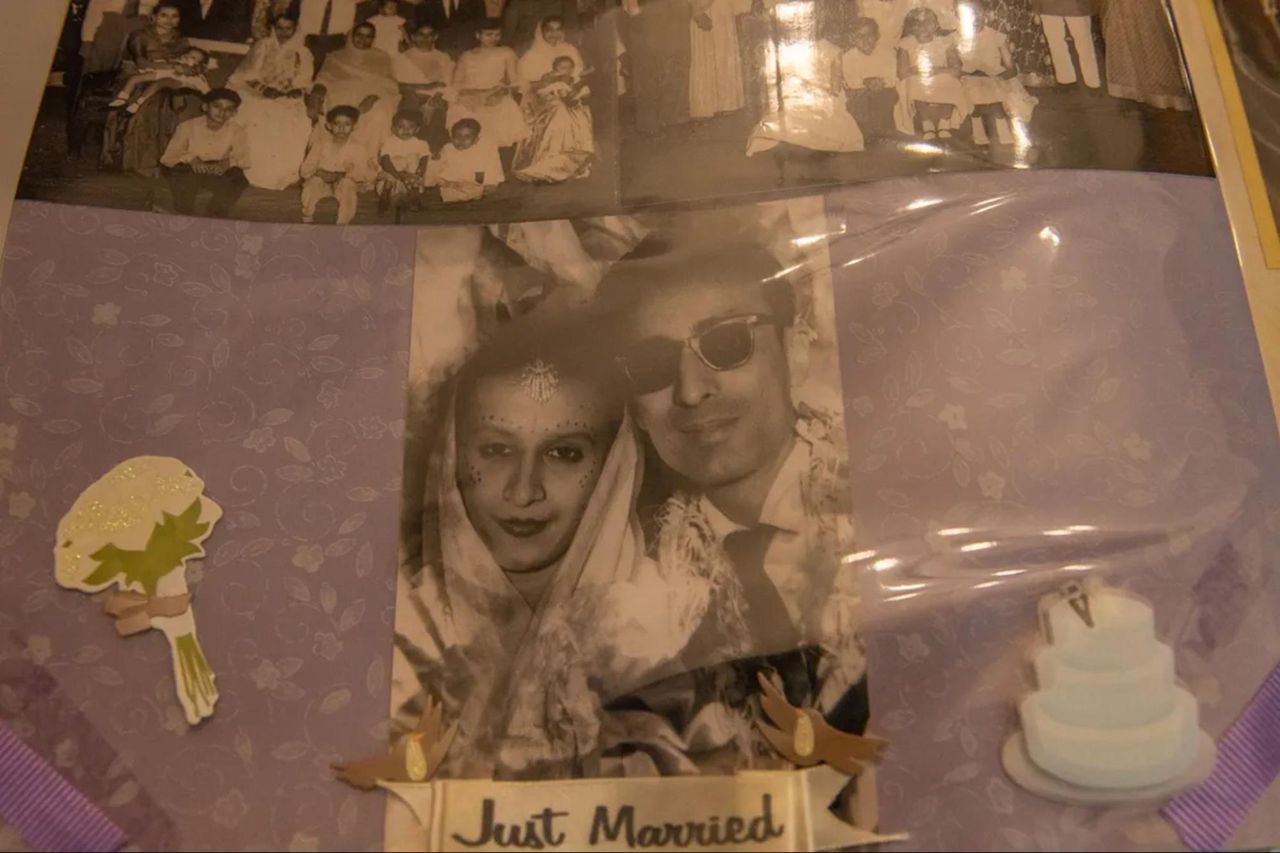

Tahera and Sabbar Khalil on their wedding day. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

Culturally competent care

Despite the demanding schedule, the Pérez-López family prefers having their father at home where they can give Doroteo the culturally congruent care that a nursing home cannot. Doroteo won’t find the caldo de gallina (chicken soup), plátano frito (fried plantain), mojarra (fried tilapia), carne guisada (stewed beef) and pepián de pollo (spicy chicken stew) that he loves on any nursing home menu.

“We don’t want him in a nursing home,” says Lilian Pérez. “He likes our traditional food — desayuno (breakfast), lots of vegetables and specialties from Guatemala.”The NCOA recommends home care because it is safer, less expensive and provides a better quality of life. However, where Latino families are concerned, the pool of culturally competent, Spanish-speaking caregivers has been dwindling steadily due to poor wages. That the Pérez-López family was able to find one so easily was more the exception than the rule.

According to NCOA director Vivian Nava-Schellinger, Latino home care workers have been underpaid and undervalued for far too long, creating serious turnover and access problems. “Almost half of these workers have incomes below 200% of poverty, nearly 88% are women, 62% are people of color, and a third are over age 55.”

Who pays for care and who delivers it?

The Pérez-López and Khalil families represent the 41 million family caregivers nationwide who provide an estimated 34 billion hours of care to an adult with limitations in daily activities, reports a 2017 AARP study.

This unpaid economic contribution was valued at approximately $470 billion. Another worrying trend reported by AARP is that 63% (2 in 3) of family caregivers aged 50+ care for an adult 65 or older.

Tahera Khalil helps her husband, Sabbar Khalil, at dinnertime. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

An NIH study of 300 family caregivers of Mexican origin and care recipients by researchers Jacqueline Angel (University of Texas at Austin) and Sunshine Rote (University of Louisville) forecasts profound gaps in senior care. They estimated that Latinos will triple by 2050 nationwide and make up one in every four Americans (28.6% by 2060). They found that as functional limitations forced Latino seniors with diabetes and dementia — two of the most common conditions among elderly Latinos — to rely increasingly on family for support, caring for them took a toll on family caregivers.

Changing the caregiver dynamic

The Angel & Rote study found that culturally tailored home- and community-based care was critical to supplement gaps in caregiver support. They also reported poor health outcomes if care was not culturally or linguistically appropriate.

What could change, says Congresswoman Anna Eshoo (CA District 14), is how we rethink the system. Eshoo moved her own parents from Fresno into her home in Menlo Park. She recommends creating a cadre of public health care counselors who are trained to answer the most common questions for family caregivers.

Sabbar hugs his son, Nazir Khalil, who is returning home to New Mexico. Nazir visits his parents frequently. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

“You don’t need 500 social workers to be answering some of the most basic questions,” she says.

Santa Clara Assemblyman Ash Kalra (CA District 27) reiterated that public health resources should enable seniors to stay at home with the support they need.

“I think that we have a long way to go in order to ensure that everyone has access to care that allows him to stay at home, rather than go into a facility,” says Kalra.

California just launched a $3.5 billion master plan that includes senior care services and an initiative that will train people to deliver home support services with cultural competency.

Brownstein has doubts about its execution.

“Who’s gonna do the training, even for things that are broadly needed, like dealing with people with dementia, much less the culturally competent needs of people from South Asia? The question is, who are the trainers?”

Innovative senior care model

One possible solution is a senior care model being piloted at Jewish Family Services of Silicon Valley. Director Susan Frazer says the eldercare project is community-funded and volunteer-driven, offering services that range from care management to scheduling medical appointments, food prep and transportation.

Seniors pay for services on a sliding scale, depending on their financial means, which is determined after a thorough evaluation of their wealth. This social enterprise model, adds Frazer, gives the community an opportunity to play a role in giving indigent seniors the services they need but cannot afford.

“The only way we can do this,” says Frazer, “is because the Jewish community gives to the Jewish community.”

Sabbar and Tahera Khalil lounge in their living room just before dinner time. Photo by Sree Sripathy for India Currents/CatchLight Local

Band-Aid solutions

As complex, long-term care needs for seniors grow in scope and intensify demands on family caregivers, the expectation that families alone will provide care for older relatives with chronic, disabling or serious health conditions is unsustainable.

Health agencies across the country have to build capacity, improve access and reduce the burden on family caregivers. Advocates need to mobilize and lobby lawmakers to make caregiving more affordable and culturally competent for older adults.

The Band-Aid solutions currently in place will not help the Péréz-López and Khalil families age in place with dignity and independence.

“To take our grandmas and grandpas and put them in those places — to think about it is stressful — so we prefer not to do it,” says Lilian Pérez.

Tahera Khalil says she often cannot find a reliable provider.

“They usually give us a list of people who can help out,” she says. “They don’t last for too long. People … they just don’t stick around. Then I just manage on my own. It’s tough.”

Without more support, the Pérez-López and Khalil families, like similarly burdened families across the country, are in danger of slipping off the caregiver cliff.

—

Meera Kymal is the managing editor at India Currents magazine and a founder/producer at DesiCollective Media. She writes about issues that impact minority communities in the South Asian diaspora through the lens of social justice, politics, and the arts.

Anjana Nagarajan-Butaney is the donor engagement advisor and a writer for India Currents magazine, showcasing the stories of South Asians in the United States while exploring the social and cultural impact of issues like immigration, health, census, elections, technology and the arts. She is also a founder of and producer at DesiCollective Media.

Sree Sripathy is a staff photographer for India Currents magazine and a CatchLight Local Fellow as part of CatchLight’s California Local Visual Desk.

Linda Jue is a contributing editor and writer for palabra. She is also editor-at-large for the investigative site 100Reporters and a reporting and writing coach for the Fund for Investigative Journalism. Among the many hats Linda has worn, she was an associate at the Center for Investigative Reporting, a magazine editor and associate producer at KQED-TV/San Francisco Focus magazine, and Northern California correspondent for C-SPAN. Her work has appeared in San Francisco Focus, KQED-TV, GEO, MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, PBS Frontline and other outlets.