Plastic-grabbing fungi could help keep microplastics, PFAS out of rivers and oceans

Researches say newly discovered kinds of fungus could be a key tool in the fight to keep man-made plastics and toxic chemicals out of rivers and oceans.

In a newly published study from Texas A&M University, researchers say three different strains of fungi showed promise in testing to remove microplastics from the water.

After evaluating more than 230 strains of fungi, the researchers settled on three that seemed most promising and tested how well they could remove microscopic plastic particles from water. The fungi would absorb the microplastics and form pellets, which can be removed much more easily than microscopic particles free floating in the water.

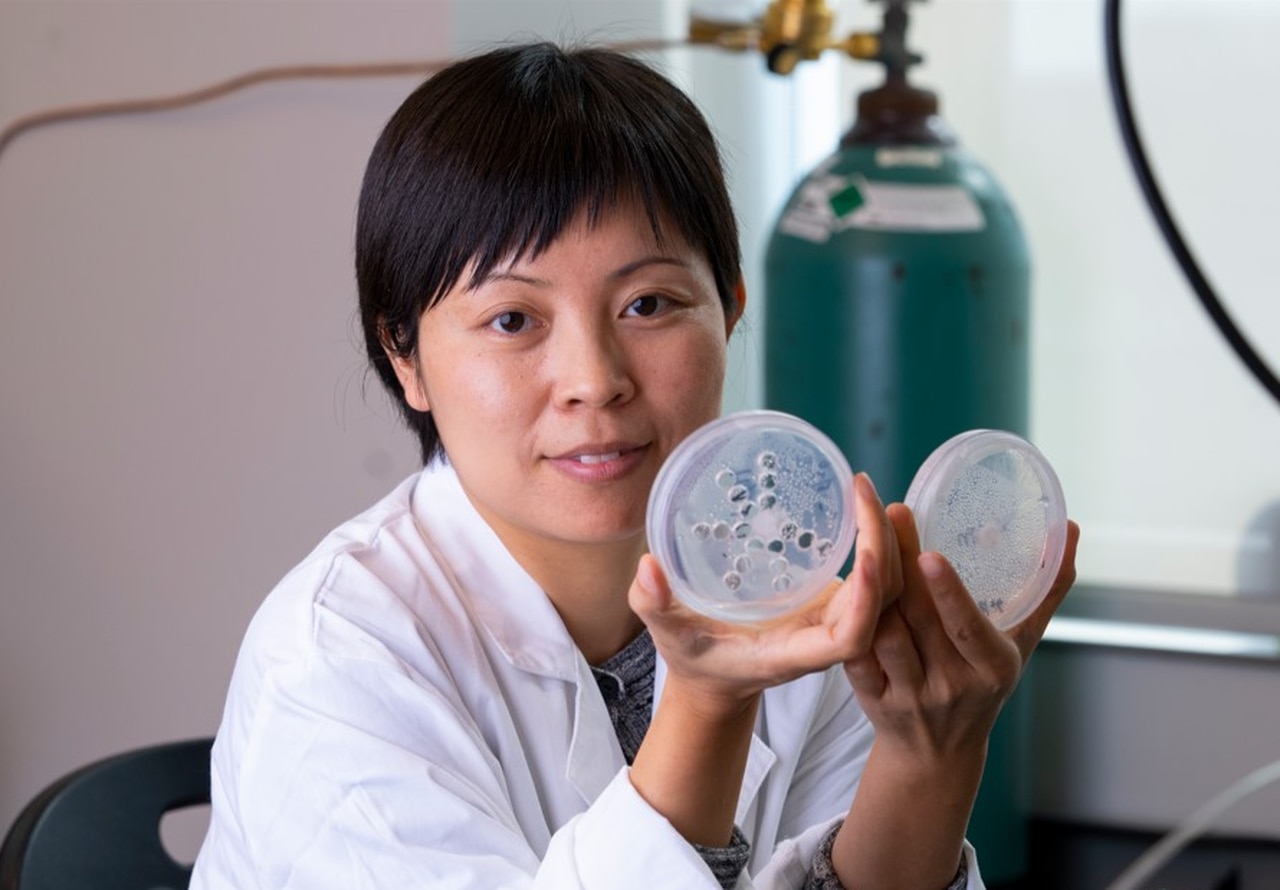

Susie Dai, an associate professor in the Texas A&M Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, told AL.com that she and her colleagues were working on using fungi to absorb chemical contaminants like PFAS and pesticides out of wastewater, when they discovered the possibility of using fungi to remove microplastics as well.

“As a result of another study when we were using fungus to decompose different chemicals in the environment, we found out when they were growing, the fungus can grow into pellets,” Dai said. “We realized that if we can utilize that for some other purpose that it could be very good.”

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic, often invisible without a microscope, that are being found in rivers, oceans and water bodies all across the world. They can come from broken down bits of larger pieces of plastic, from some health and beauty products like facial scrubs, or from synthetic fibers in clothing or other products.

Those fibers shed in the laundry and often get washed down the drain and sent to wastewater treatment plants that aren’t equipped to capture all of them. Then they float into creeks or rivers and ultimately the oceans.

SEE MORE: Fighting microplastics at home: There’s some seriously gross stuff in my laundry

Studies in recent years have shown very high levels of microplastics in Alabama in both the Tennessee River and in Mobile Bay.

These particles can be absorbed into the tissue of humans, fish and other animals, though we don’t know much about how that might affect animals or people.

“Previous studies have indicated that sub-micrometer microplastics can easily travel considerable distances in the environment, infiltrating plant root cell walls,” Huaimin Wang, another of the researchers who conducted the study, said in a news release. “They have even been shown to have been transported into plant fruiting bodies and human placenta.”

But now, initial studies are showing that these often microscopic particles of plastic can be concentrated with a fungal growth and then removed

The researchers say their fungi could potentially be used by wastewater treatment plants to remove more microplastics and prevent them from reaching the oceans.

They tested three different fungi strains that showed promise, one variety of aspergillus fungus and two white rot fungi strains that had not previously been isolated.

Researchers said the aspergillus was able to remove up to 100% of certain kinds of microplastics and nanoplastics from water samples. The two white rot fungi also showed “assimilation potential,” according to the paper.

However, there are many many types of plastics in the world, and it’s not clear that the fungi would be effective at removing them all at all sizes. Dai said the ideal solution is to find types of fungi that can both capture microplastics and also break down chemicals like PFAS, pharmaceuticals, pesticides and cleaning products that may be harmful in the water.

Most wastewater treatment plants capture around 90% of microplastics, which means that about 10% get discharged into rivers and then oceans. The authors propose that fungi pellet filtration units could be added at the end of the standard wastewater treatment plants at a relatively low cost that would reduce that 10% to around 0.1%.

One previous study estimated that effective wastewater treatment plant filtration worldwide could reduce the amount of microplastics released into the environment by up to 90%.

Dai said the ultimate goal would be to recapture those microplastics from the pellets and potentially even recycle them into new products.

“What we’re interested in is how potentially can recover them,” Dai said. “That’s an ongoing study to find different micro organisms, or pellets to absorb the plastics and then recover them so you can reuse them.”

In addition to her research on microplastics, Dai has also conducted studies on using fungi to remove PFAS — so-called “forever chemicals,” linked to cancers and other serious health problems.

PFAS are extremely slow to break down in the natural world, and people and animals can build up high levels of these potentially dangerous chemicals in their bodies over years of exposure.

These man-made chemicals are used in many consumer products ranging from food wrappers and packaging, to dental floss, fire-fighting foam, nonstick cookware, textiles and electronics.

Dai’s new technology uses a plant-derived material to absorb the PFAS and dispose of them by means of microbial fungi that literally eat them.

The ultimate goal, she said, is to develop a fungal system to add to wastewater treatment plants that can both break down unwanted chemicals, but also capture microplastics.

“If you can decompose those unwanted chemicals together and you can remove those microplastics from the water, your effluent after this type of treatment will be much cleaner to be released into into creeks and into rivers,” Dai said.