How a 16th Street Baptist Church bombing victim healed by mentoring Black boys

After the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, 11-year-old Dale Long stumbled from the rubble and went on to find healing by helping others.

Long and his younger brother, Ken, were unharmed by the blast on Sept. 15, 1963. But it psychologically shook their family. Bombings were common white supremacist weapons of choice as civil rights leaders fought to integrate schools, neighborhoods and businesses in Birmingham, Ala. Long’s father was a manager at the Black-owned A.G. Gaston Motel, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. slept and strategized with other leaders, such as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. The motel was bombed four months before racial violence shook the church congregation and killed 14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and 11-year-old Denise McNair.

Although Long and the four little girls went to different schools, the interconnectedness of the Birmingham neighborhoods and the community-first environment of Black churches made them close. Wesley and Long played clarinet together in the orchestra. Long was always captivated by the singing voice of McNair’s mother, Maxine, when she sang solos in the church choir. McNair’s father, Chris, was a prominent photographer who not only snapped pictures celebrating Black life, but captured many of the events of the Civil Rights Movement.

“It wasn’t just a matter of four girls losing their lives. These were girls that we knew,” Long said. “We had known them all their lives and vice versa.”

Long’s grandmother had a mantra to help herself and her family endure the turmoils of segregation and racial violence: Pray, have faith, walk uprightly and get a good education.

But as she tried to console Long and his brother after the bombing, she added another piece of advice.

“She said, ‘Boys, you need to make up in your minds that you will do something for somebody else,’” Long said. “‘Could have been four little boys.’”

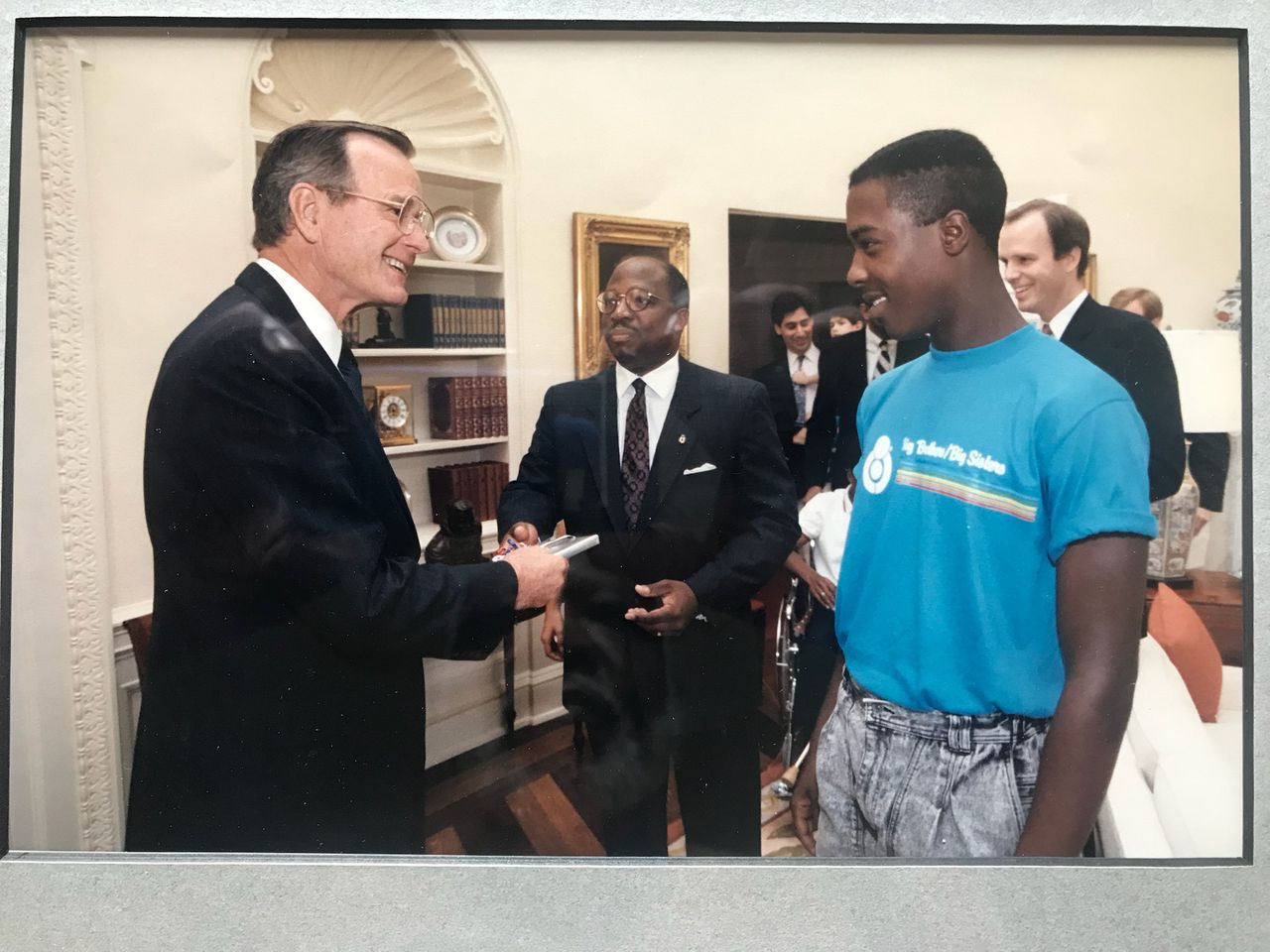

Now 71, Long has spent almost five decades following his grandmother’s guidance by being a mentor for Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. He has empowered multiple young men within that time as he guides them through high school and into young adulthood. Long was so dedicated to his job as a mentor that he became National Big Brother of the year in 1989, receiving the opportunity for himself and his “little brother” at the time, Michael, to visit the White House and meet the then President George Bush.

A member of the historically Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, not only is Long trying to match up his frat brothers with “little” brothers, he wants to galvanize the rest of the Divine Nine family to help him get 30,000 boys off the Big Brother Big Sister’s waitlist. These youth deserve a village that supports them too, he said.

“If we don’t mentor our young boys, the police will,” Long said. “In order to be a man, they have to see a man.”

President George Bush (left) smiles at Michael (right) after Dale Long (middle) becomes Big Brother of the Year in 1989.

Long had an epiphany while being in the presence of King, who was also an Alpha man. As a child, Long had admired King’s oration from afar through TV interviews and articles in Jet magazine, Ebony and Time. He was even close friends with King’s nephews who lived in Birmingham. A few days after the bombing, Long met the civil rights icon in person after King delivered a cathartic eulogy for Collins, Wesley and McNair.

Long was about 10 feet away from a hearse parked outside the crowded church where the funeral was held when he locked eyes with King, who was leading the recessional. Long froze as he thought of his next move. He thought about hugging King, but thought better of it considering the heaviness of the moment. So Long briefly looked away. But when he looked back around, King was still looking at the young boy. The moment only lasted about two to three minutes and they didn’t exchange a word, but it prompted a shift in his spirit.

As pallbearers hauled three caskets into the hearses, Long fused that moment with the wise words his grandmother gave him days prior. He kept that moment close throughout his life.

“I’ve been to the White House. I’ve shared the podium with President (George) Bush. I’ve done a whole bunch of other stuff, but nothing to compare to standing there with King,” Long said. “I was trying to imagine what could be going on in his head…and he had to think that the effort that he was making in leading the demonstrations, the SCLC and all of that was gonna make life better for me because I was a youngster at the time.”

He didn’t join Big Brothers Big Sisters until after he pledged Alpha while attending college at Texas Southern University, an HBCU in Houston. A frat brother tried to convince him to become a mentor, but Long was focused on perfecting his musical skills because of his band scholarship.

Long played with the same clarinet his parents bought for him as a child. They also invested in his musical talent by getting him an alto saxophone for Christmas when he was 13. Long was so happy, he hopped on his bike, made his way to the music store to pick up the “Tune A Day For Saxophone” book, and spent his entire winter break teaching himself how to play. His mastery of the instruments was evidence of Birmingham’s big band music culture and the emphasis of education in the city.

“That was the kind of atmosphere the teachers created for us to have. We had that type of attitude of, ‘You go out and get it done. Whatever it takes,’” Long said.

After graduating college in 1974, a coworker convinced Long to sign up to be a big brother, but only for a day. He was matched with a teen named Keith . Their first meeting was during a Houston Astros baseball game. Long admits that he used the moment as bait at first because he also invited a pretty young lady he was trying to impress with his good deed at the time.

Realizing his mistake, Long used the later half of the game to talk with Keith, who strummed Long’s heart strings after revealing that he was adopted, but his adopted parents had since divorced.

“That means he had been rejected twice, and that got my attention,” Long said.

At the end of the game, Keith tugged at Long, looked him in the eyes and Long felt a familiar feeling.

“The same type of moment I had when I was standing and looking at Dr. King at 11 years old – that same thing that went through my entire body,” Long said.

At that moment Keith asked, “Mr. Long, are you going to be my big brother forever?”

Long was sold and responded, “Of course.”

Long signed up for Big Brothers Big Sisters for good and the pair would be better together for about seven years. Keith was even in Long’s wedding to his current wife of 50 years. One of the toughest decisions Long had to make was breaking the news to Keith that Long was moving from Houston to Dallas for a job opportunity. But the Longs kept in contact with Keith for as long as they could by taking him out to lunch or even a Texas Southern football game when he visited Houston.

Long eventually lost touch with Keith, but he kept looking out for his first “little” as he continued to be matched with seven other teen boys over the past 49 years. This dedication led to many memorable moments for both Long and his littles. Around the same time as Michael and Long’s White House visit, the pair worked together to convince Alpha Phi Alpha’s leadership to create a partnership with Big Brothers Big Sisters. The pair was successful, and for the past 30 years Long has been matching frat brothers nationwide to young Black men who need mentors as the national chairman of the Big Brother Big Sisters partnership.

His time with Michael was so influential, that after Michael graduated from high school, he decided to follow Long’s lead despite being busy with his barber business.

“He served for a little bit as a big brother himself,” Long said. “And that was rewarding to me because, out of all of the eight boys that I was matched to, Michael chose to give back himself.”

As Long travels down from Dallas to Birmingham to commemorate the 60th anniversary of bombing, he doesn’t shy away from the gravity of the tragedy. He recognizes that mental health services were not provided to children enduring the terror of the time. And he knows people who haven’t psychologically healed since the bombing.

At the same time, he recognizes that giving back multiplies joy. Mentoring gives him space to change someone’s world one — as well as his own — moment at a time.

“Do I think I’m a better person for having lived through that tragedy? Absolutely. And hope I’ve lived up to what my grandmama talked about,” Long said. “We have mothers and grandmothers trying to raise these boys, and they’ve said they want black men to mentor them. So we’re gonna do it. Whatever it takes.”