School drug programs move beyond punishment to relationship-building

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

By Mariela Murdocco

In August 2022, a 16-year-old student at Red Mesa High School in Apache County, Arizona collapsed outside the school cafeteria, foaming at the mouth. He had overdosed on a cocktail of street drugs and harsh homemade alcohol.

Fortunately, he survived. But the incident terrified Amy Pérez Fuller, superintendent of the Red Mesa Unified School District. “His heart rate was off the roof,” Pérez Fuller said. “He was non-responsive. I thought he was going to die.”

The incident at Red Mesa school was not isolated. Across the U.S., secondary schools have become hot spots for illegal drug dealing and consumption. About 22% of high school students reported being offered drugs on school property in the previous 12 months, whereas over the prior 30 days, 22% said they used marijuana and 29% admitted to drinking alcohol, according to a 2019 survey by the National Center for Education Statistics.

Using alcohol and drugs as an adolescent can lead to unsafe driving and risky sexual behavior, cause permanent damage to developing brains, and even result in lifetime addiction. Immigrant families and students of color face unique challenges in preventing and addressing drug abuse, from the cost of treatment programs and cultural and language barriers to high-quality information and care. Punitive measures, school suspensions, and excessive monitoring are often ineffective — and may in fact contribute to drug use, research suggests. The solution, experts say, are evidence-based prevention programs that teach social and refusal skills from an early age, educate families, and enlist school staff in prevention.

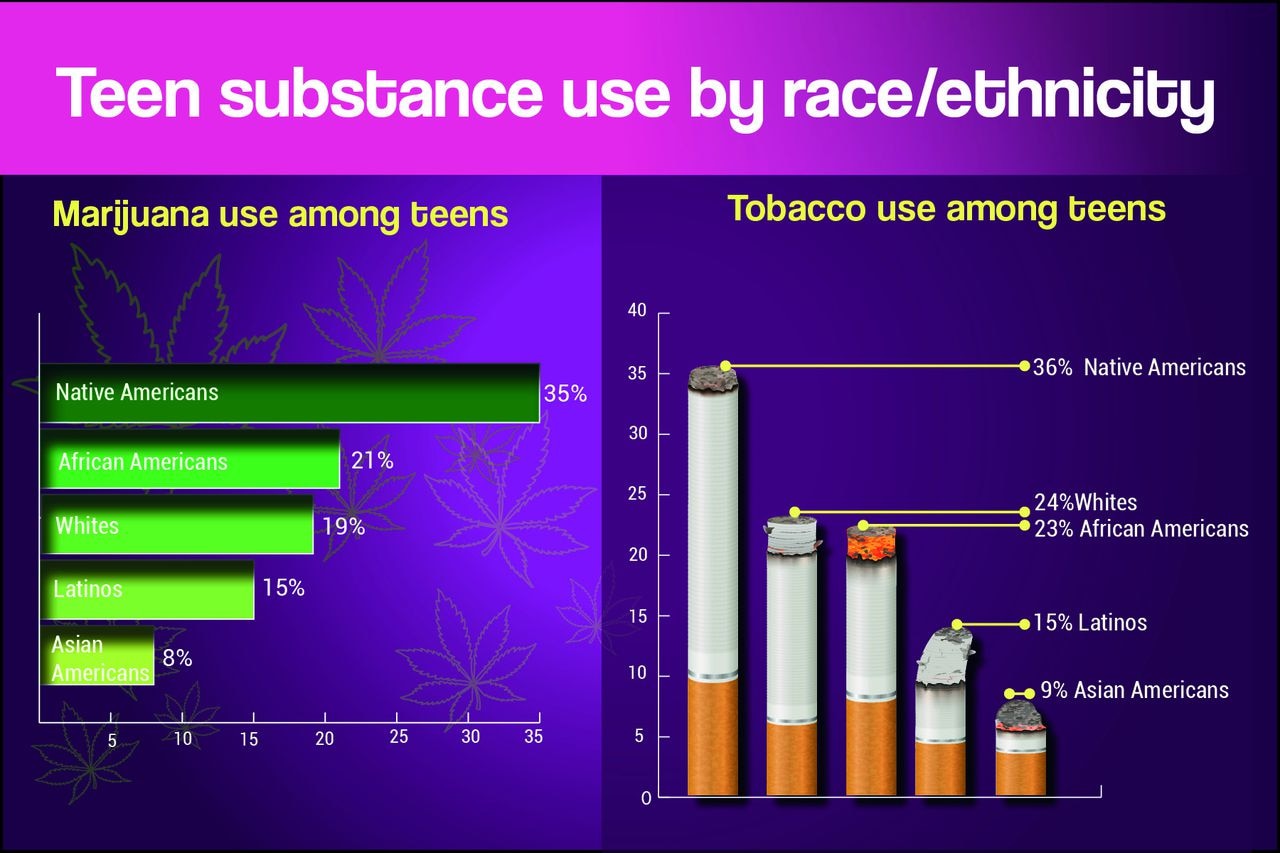

Source: A 2021 study by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Infographic by Stef Arreaga for palabra

“If we just focus on the student and not on the environment, it’s not going to be successful,” said Pérez Fuller.

Research shows that programs that aim to persuade or make students “scared straight” don’t work, she said. “Once you understand what (a drug) does, once you have the language that is given to you, you know how to refuse, how to leave. We’re not the punishers. So we have to teach them.”

Widespread use of drugs and alcohol

While James was in middle school and high school, vaping with e-cigarettes in the school bathrooms was the norm at the private institution in Manhattan he attended on a scholarship. (James’ name has been changed at his request to avoid potential negative impact on his career.)

“There’d be people with their pens and stuff with cannabis oil,” said James, from Queens, New York, who is now 19 and studying computer science in college in Iowa. He first tried marijuana with his friends when he was around 15 but didn’t start smoking regularly until his senior year.

The U.S. has one of the highest rates of teen drug use in the world, with almost 25% of 12th graders using, according to Nora Valkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Over 2021 and 2022, about 31% of 12th graders used cannabis and 27% vaped nicotine, while 52% used alcohol in 2022, according to Monitoring the Future, an annual study conducted by the University of Michigan since 1975.

At school, students most often vape in stairwells and restrooms because there are fewer adults in those spaces and, in the case of bathrooms, there are no cameras, said Stephen Walton, assistant principal at Fannie Lou Hamer Middle School in the Bronx, New York, where the student body is 65% Hispanic, 29% Black and 3% white. Four years ago, there was no vaping at the school, said Walton. But it’s on the rise. “This year we’ve probably confiscated about, let’s say 12 to 15 vapes,” he added. “But we’ve also had probably another 10 instances where people said they knew someone was vaping but we did not find the devices.”

Some parents are wondering if schools are safe environments. “I am terrified of the lack of concern the school seems to have,” said Angelique Ortiz-Cameron. Her twin eighth-grade daughters had stopped using the main restroom at their middle school in Leonia, New Jersey, because it was the popular spot to vape, preferring the upstairs bathroom. “I don’t want them to develop bad habits that could be dangerous later in life,” Ortiz said. “I was surprised to hear there is a lot of vaping and marijuana usage at schools.”

Pérez Fuller said that many students in her district start using drugs at home before they enter the school. “By the time they come to the school they’re already under the influence of something like marijuana,” she said. Like in other schools, Pérez Fuller says drug use at Red Mesa High School often happens in the restrooms.

Angelique Ortiz-Cameron and her twin daughters outside their school in Leonia, New Jersey. Ortiz-Cameron wishes the school would provide more information or offer workshops to address vaping in the restrooms. “Maybe the parents will look out a little bit more for this situation,” she said. Photo by Mariela Murdocco for palabra

Colorful and flavored vaping products increase the appeal for kids. Valkow said it’s dangerous. When vaping any substance, you may consume higher content than smoking. Vaping high doses of nicotine, the addictive substance found in cigarettes, or THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, can land teens in the emergency room, she added.

Potent opioid drugs like fentanyl are extremely dangerous, Valkow said. “It could be fatal in tiny doses. Fentanyl is increasingly infiltrating the illicit market through counterfeit pills, including for teens who may seek out prescription medications, like Adderall or benzodiazepines.” Fentanyl-related overdose deaths in the 10-to-19 age group increased by 182% from 2019 to 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The younger kids are when they first use drugs or alcohol, the higher the lifetime risk of addiction. Addictive substances change neural pathways and may permanently damage the developing brain.

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Infographic by Stef Arreaga for palabra

“If a kid is in eighth grade when they first try drugs and alcohol, they have almost a 50% chance during their lifetime of developing addiction,” said Jessica Lahey, a Vermont-based educator and author of the book The Addiction Inoculation. “The average age of initiation into drugs and alcohol in the United States is around 13 1/2. It really affects learning, maturation. It affects kids’ executive function, not to mention all of the risks that alcohol brings along with it in terms of accidental death.”

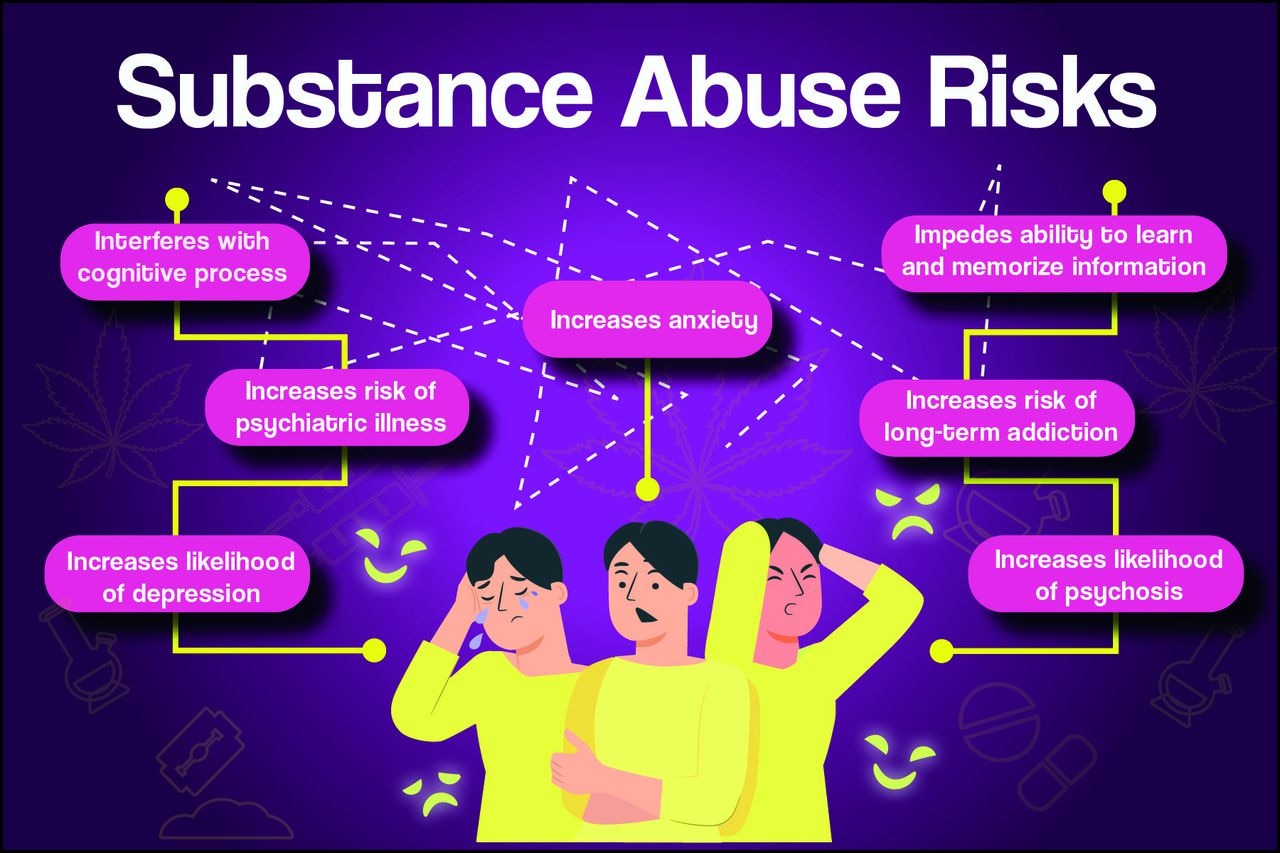

In Lahey’s experience, the public doesn’t fully understand how much damage substance abuse can do to the adolescent brain. Addictive substances may damage the brain at a crucial time of development, which continues until around age 25. They also impact learning and judgment.

“Drugs interfere with cognitive processes,” Valkow said, noting that marijuana use is associated with higher risks of psychiatric illness and nicotine may increase depression risk. “Marijuana, for example. If you’re vaping, you’re going to basically be unable to memorize or learn new things.”

Risks for low-income students of color

Although Latinos are among the ethnic groups with the lowest rates of drug consumption, they may be uniquely vulnerable. According to a 2021 study by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, one in 10 Latino adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 had consumed illicit drugs.

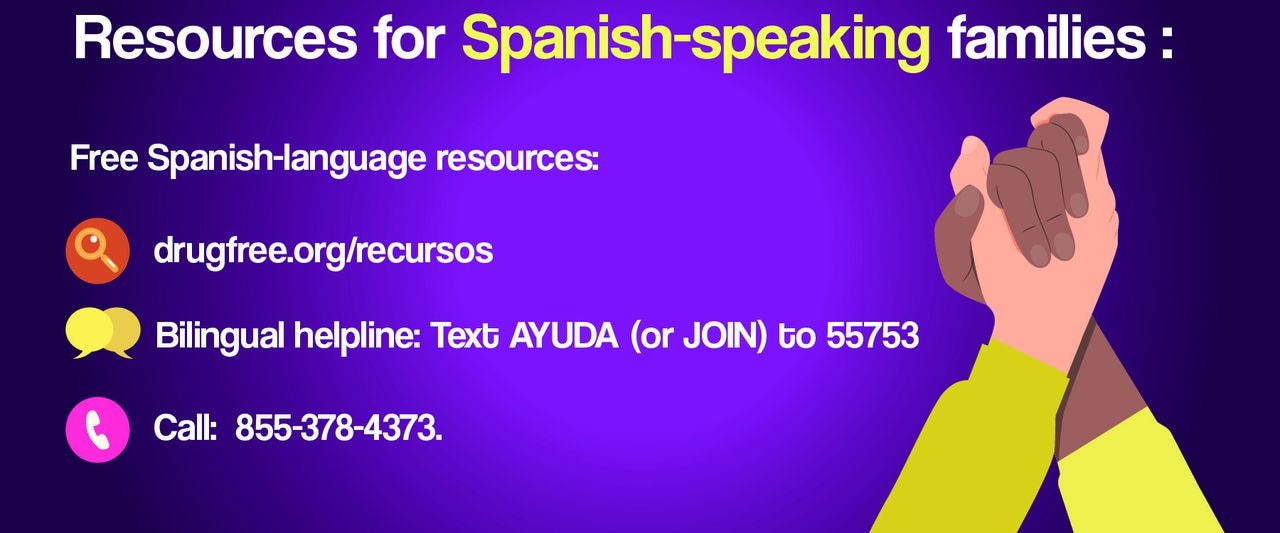

Being a person of color can mean facing higher levels of intolerance and discrimination. This is particularly true for immigrant families and those who are undocumented, said César Bravo Wolfe, associate director for Partnership to End Addiction, a New York-based nonprofit that offers drug addiction and prevention program guidance through research, advocacy and helplines for families. Bravo, who also serves as a bilingual helpline specialist at the nonprofit, notes that when calls come from families fleeing poverty or violence in their home countries, the trauma of the immigration process and the fear of deportation aggravate the drug problem.

César Bravo Wolfe, in his office in Rochester, Minnesota, emphasized the importance of communication with teenagers, not being punitive, establishing strong communication, and building a support system. In 2022, Partnership to End Addiction supported about 20,000 families through their programs with 11 helpline specialists. Five of the specialists were bilingual. Photo courtesy of Partnership to End Addiction

“They don’t feel comfortable talking to official channels,” Bravo said, emphasizing the importance of being able to seek help anonymously. He said the majority of the calls — free and confidential — are related to marijuana use and dabbing, which is vaporizing concentrated cannabis oil.

At Fannie Lou Hamer Middle School, some students who are immigrants to the U.S. have had horrific experiences “being separated from their families or dealing with racism,” said Walton, an assistant principal.

Young immigrants are under pressure to function in a bicultural, bilingual world, which can create a stressful sense of not belonging anywhere, particularly in mainstream American society, said Flavio Marsiglia, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Social Work and director of the Global Center for Applied Health Research. This makes them vulnerable to drug use. Anti-Latino sentiment is also a factor, Marsiglia said, “They think, ‘If my friends offer me something to smoke or drink, they will like me better because I will be part of the group.’”

Intoxicating substances and products are more available in neighborhoods of color, as are stores that sell and advertise drug paraphernalia like vapes, liquor, Phillies blunt cigars and hookahs. “One of the issues is that it’s so accessible,” Walton said, referring to the South Bronx area. “There are four bodegas within a three-block radius of the school, and they all sell these vaping devices,” Walton said.

Students outside their school in Leonia, New Jersey. Increasingly, teachers find that their obligations aren’t just teaching, but also making sure that their students are secure in a safe environment. Photo by Mariela Murdocco for palabra

According to Linda Richter, senior vice president of prevention research and analysis for Partnership to End Addiction, “One of the most important risk factors for substance use among young kids is being exposed to it and having it accessible around them — a greater problem for people of color than for white kids.”

Moreover, many students of color might not have as many resources for inpatient treatment, which can cost between $15,000 to $27,000 for a 30-day stay, according to American Addiction Centers. Many programs take private insurance. Some accept Medicaid patients and will admit undocumented immigrants; the latter, however, often struggle to gain access. Treatment may include motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy, and individual counseling, said Marsiglia. In some instances, medication can be an effective part of treatment, he added.

In addition, James, the college student, pointed out that if students from marginalized backgrounds are expelled from school because of drug use, the consequences could potentially be more severe than for more privileged classmates. “The wealthier kid can definitely afford to bounce back,” he said, but a student like him who came from a low-income family and relied on a scholarship might not be accepted in another school.

Punitive measures don’t work

There is no simple solution to the problem of drug use in schools, in part because pills, edible cannabis and nicotine devices are easy to hide. “I understand the frustration of parents that (their) child should be able to go to the bathroom without being surrounded by other kids using drugs or offering it to them,” said Richter.

Beatriz Peláez-Martínez, a Spanish and Italian teacher at Tenafly High School, said that if a teacher suspects a student is under the influence of alcohol or drugs — even if they are not — they are obligated to report it to administration, take them to the nurse and call the parents. “That’s a health issue that is impacting a specific child. How that kid is getting it is also a problem.” Photo by Mariela Murdocco for palabra

Some schools have adopted measures like installing smoke detectors and removing the bathroom entrance doors, as is the case at Tenafly High School in New Jersey. “Kids, unfortunately, do vape in the bathrooms,” said Beatriz Peláez-Martínez, who teaches Spanish and Italian, as we walked through the corridors. Staff members sometimes check the bathrooms; other times students inform the staff that others are vaping. But by the time an adult gets there, the kid is gone. “They have to go and look at the cameras in the hallways,” she said. “Kids can be identified, but it’s not always foolproof.”

Bravo counsels families by phone, text, Facebook, email, and an online community support group. He encourages callers to communice with their children in productive ways. “We talk about something we call communication traps,” he said. “Fear is one of them; a sermon is another.”

Source: Partnership to End Addiction, The Addiction Inoculation. Infographic by Stef Arreaga for palabra

He emphasized the importance of being informed and establishing trusting parent-child relationships so young people will feel safe, be more honest about what they are going through, and come to their parents for support. “Caregivers and parents play a key role,” said Bravo, noting that confrontation and punishment — even when delivered with love — are never the right path. He advises “establishing good communication” and “not to scare them.”

“Don’t punish them,” Marsiglia said. “That creates more distance between the parent and the child. You want to narrow the distance, not make it wider.”

Punitive measures at schools, like out-of-school suspensions, are damaging and disproportionately harm students of color, giving them more time to engage in drugs, noted superintendent Pérez Fuller. “We call the counselors to help them with their addiction, but we don’t kick them out of school.” That approach is new for some Navajo and Latino parents whose first instinct is to punish children, an approach that worsens the problem, she said.

Schools like Tenafly High School opted to install smoke detectors and remove the restroom entrance doors to avoid having students hide to vape. Photo by Mariela Murdocco for palabra

What are the solutions?

In Pérez Fuller’s previous school district, Florence Arizona, a program called Manténte Real (keepin’ it REAL) successfully reduced drug use, paraphernalia, and the need for drug-related discipline, year after year. The bilingual community-based substance use program reports measurable reduction in drug use among youth in Arizona, across the U.S., and in other countries, including Uruguay, Spain and Mexico. REAL stands for Refuse, Explain, Avoid, and Leave, the core of the strategy. “Sometimes kids don’t have the skills to deal with offers and they don’t know what to do,” explained Marsiglia, one of the program’s creators.

A study of 1,364 students in 35 middle schools in Phoenix found that students that went through keepin’ it REAL stopped alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use at a rate that was 61% higher compared with other programs. Marsiglia and his colleague published their findings in Prevention Science in 2007 and 2003, and have reported positive results in students around the world since then.

Programs that successfully prevent substance abuse provide pre-adolescents with life skills, strategies, and tools to deal with risky situations, research shows. “It’s about giving kids real information, the skills, and the tools they need in order to feel comfortable saying no,” Lahey said.

Angelique Ortiz-Cameron and her twin daughters at home in Edgewater, New Jersey. Keeping adolescents active and establishing trusting parent-child relationships play key roles in preventing substance abuse.”I’m a very involved mom,” said Ortiz-Cameron, whose daughters are involved in soccer, basketball and track. Photo by Mariela Murdocco for palabra

Keepin’ it REAL focuses on the needs of the Latino community, with the Spanish version of the program customized to adolescent immigrants. The program includes culturally and linguistically adapted videos that children helped produce. Keepin’ it REAL is taught by a classroom teacher, who “is the best person to do it, because he or she already knows the kids and there is a relationship,” said Marsiglia.

Lahey emphasized that the most effective programs start as early as kindergarten, like Botvin Life Skills, an evidence-based program that teaches students social and emotional skills to prevent substance use.

“Most places here in the United States wait until middle school or high school to even start talking about drugs and alcohol,” she said. “They’re waiting too late.”

Marsiglia agrees. “They have to be part of the conversation from an early age. Then it becomes natural. Every child should get this kind of prevention program.”

Infographic by Stef Arreaga for palabra

Visit Drugfree for support in English, or this link for support in Spanish.

—

Mariela Murdocco, a bilingual multimedia journalist and photographer, has been nominated for five Emmy Awards. Born in Uruguay and based in New York City, she began her two careers simultaneously in 2002. She has worked as a reporter, television producer, anchor, photographer and videographer for Consumer Reports, Telemundo, News 12, The New York Daily News, Banda Oriental, The Jersey Journal and The Associated Press. She was a correspondent for Canal 7 in Uruguay and has contributed to The Guardian, The Huffington Post, Hola TV and Fox News. In 2012 she was elected national Spanish at-large officer for the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

Stef Arreaga is an investigative journalist living in exile in the U.S. She was born in Guatemala during the bloodiest period of a war that lasted almost four decades. She then carried out investigative journalism for the alternative media, where she has worked on issues related to historical memory, mining, extractivism, megaprojects, monocultures, land dispossession, criminalization and malnutrition, especially communities that have historically been oppressed . In 2017, she began investigating and documenting the case of the fire at Hogar Seguro Virgen de la Asunción, where 41 girls were burned to death and 15 managed to survive. She also conducted workshops on community journalism for Central American journalists working within grassroots, farmworker, and women’s organizations. Many of these journalists face criminalization and persecution for their documentation efforts.

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning science journalist covering children, behavioral and mental health, education, race, gender, disability, and related topics for the Atlantic, New York Times, Undark, and Washington Post, among others. Her book, The Good News About Bad Behavior, grew out of Mother Jones’ most-read story. A Harvard physics graduate, Katherine is the founder of the Institute for Independent Journalists and former national correspondent for Newhouse and Bloomberg News.