Birmingham zoo plans to relocate graves to build new exhibit: 5 things to know

The Birmingham Zoo is built atop land where some of the city’s earliest poor residents are buried.

As the zoo plans to add a new cougar exhibit, officials are asking the state for permission to dig up and relocate about a dozen graves to make way for the expansion.

Here’s what we know about the plan:

The zoo is expanding to add a new cougar exhibit.

The new zoo exhibit, called Cougar Crossing, will include Bob, the zoo’s current bobcat, in addition to a new cougar. It will be 15,000 to 20,000 square feet, including a public viewing area along with two outdoor habitats.

Zoo officials hope to open Cougar Crossing next summer.

A planned Birmingham Zoo exhibit named Cougar Crossing will feature the zoo’s current bobcat along with a new cougar. To make way for the project the zoo is seeking to move about a dozen human graves located on the property. (Contributed artist rendering from the Birmingham Zoo)

The zoo plans to move about a dozen graves to make way for the exhibit.

About 4,700 people are buried on the land beneath the zoo and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens. The zoo’s plan is to dig up the graves of 12-15 people and rebury them nearby on the property.

The burial ground, formerly known as Red Mountain Cemetery and Southside Cemetery, was abandoned when a graveyard for the indigent opened in Ketona around 1909.

In 1934, the Birmingham City Council dedicated the entire 200-acre parcel as Lane Park, a public park named in honor of former Mayor A.O. Lane.

The zoo opened on the land in 1954, and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens followed eight years later.

A historic marker notes the history of the area known as Lane Park. A cemetery with more than 4,700 people are buried on the site that is now the Birmingham Zoo and nearby Botanical Gardens. (AL.com File/Jeremy Bales)

The zoo needs approval from state regulators.

The Birmingham City Council this month voted unanimously to endorse the zoo’s plans, which are pending approval from the Alabama Historical Commission. The proposed plan seeks to build on the site while also being respectful of those who are buried there, said Chris Pfefferkorn, president and CEO of the Birmingham Zoo.

If the plan is approved, an archeologist from the University of Alabama will excavate the site and collect any remains and items interred there. The remains will be placed into new wooden boxes, as specified by the Historical Commission, for reburial.

Some of Birmingham’s earliest residents are buried on the land.

More than 4,700 indigent people were interred at the old cemetery between 1888 and about 1909. Many were buried in simple or unmarked graves.

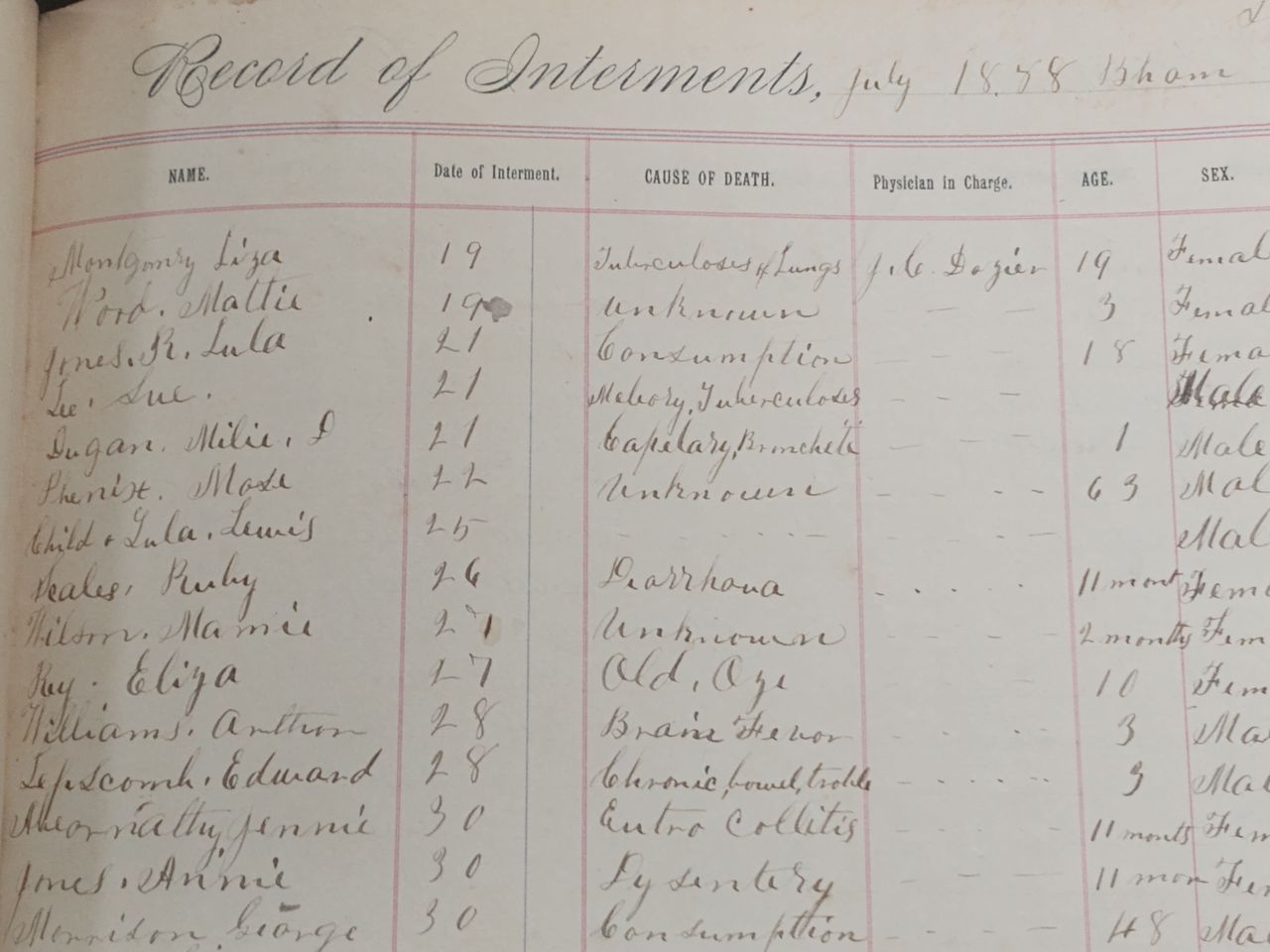

A hand-written ledger, housed at Birmingham’s Linn Henley Research Library, lists the names, ages, races, causes of death, and sometimes the supervising physician in charge of the interment. Yet many of the entries are unnamed, simply entered as “unknown.”

Read more: Who are the people buried on the Birmingham zoo grounds?

It is nearly impossible to know which people’s graves will be relocated, as there is no map identifying where individuals are buried.

A ledger, at Birmingham’s Linn Henley Research Library, lists the names, ages, races, causes of death, and sometimes the supervising physician in charge of the interment at the old Red Mountain and Southside Cemetery. Today, the land houses both the Birmingham Zoo and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens.

The zoo isn’t the only Birmingham attraction built atop an old cemetery.

Historians have identified other burial spaces which, over time, have been abandoned and redeveloped. That includes Legion Field, built in 1927 on top of 322 graves, according to Scott Martin, vice president and education chairman for the Alabama Cemetery Preservation Alliance.

The headstones of about 175 Black people and about 140 White people were removed for construction of the stadium, but the bodies were not, according to records from the federal Depression-era Works Progress Administration, which provided a variety of services including historical research and documenting cemeteries.

Kathryn Shoupe, a spokeswoman for the Alabama Historical Commission, said the commission routinely works with cemetery owners, developers, and government agencies to make plans to protect and preserve cemeteries. But until receiving the zoo’s application, the commission has not received a request to relocate graves in at least five years, Shoupe said.

Crews prepare for an expansion of Legion Field Stadium in 1947. The stadium opened in 1927 as a 21,000-seat venue. It eventually grew and became known as the “Football Capital of the South.” (Birmingham News file)